Lahore

Lingering Fragrance

She needed some green in her apartment.

Before she bought furniture, she was at the flower shop – a subconscious evocation of a fecund childhood, romping in gardens, rolling in lawns, clambering mango trees, picking flowers in the morning for the breakfast table…

“Philodendrons, lilies, ferns, azaleas, bonsai…”

Hmm. She spends long minutes gazing at each plant, fingering the leaves, feeling the texture, inhaling its aroma.

“I’m sorry, I just can’t decide!” she smiles apologetically at the Chinese lady behind the counter. “Everything is lovely, but…” What do I want?

Then, among the flowering pots, in a tangle of pink, yellow, purple, red, blue, she spies a familiar star-shaped white…

She blinks, startled. Is it? It can’t be…bending forward, she buries her face in the modest little shrub bearing the two pale-faced flowers and takes a deep breath…

Suddenly, she’s not in Brooklyn.

She’s in a garden in Lahore on a warm summer’s night. The grass is damp from the afternoon rain. Crickets and other invisible creatures of the dusk trill madly in the bushes, and a velvety breeze rustles in the bougainvillea creepers and Gulmohar above, filling the air with a shower of orange and fuchsia…

It smells sweet, but a subtle kind of sweetness – of budding love, and clasping a dear one’s moist hand, of late-night drives and dewy white bracelets bought from the barefoot little boy on the curbside, of cooing pigeons and clouds of fluttering wings on the rooftop, of twinkling black eyes rimmed with kajal, white blooms wreathed in black hair, and the enveloping scent of flowers in a bride’s bedroom…

“So you want the jasmine, miss?” The Chinese lady grins, her cropped black head nodding vigorously, round black spectacles bouncing on her nose.

Jasmine! Motia…

“Yes, I’ll take the jasmine,” she nods vigorously back.

It sits on a windowsill in her apartment, in a modest little green pot – spreading its delicate, memory-laden perfume over the folds of her new life, a graceful remembrance, a lingering fragrance of the past.

Is there a Pakistan to go back to?

Published in The Express Tribune Blog, January 20th, 2011

Last week, my husband and I finally booked our return tickets to Pakistan. It was a proud moment, a happy moment, not only because we had been saving to buy them for months, but because we had not been home in nearly two years.

Two years! It seemed like a lifetime. We had missed much: babies, engagements, weddings, new additions to the family and the passing of old, new restaurants and cafés, new TV channels, even the opening of Lahore’s first Go-Karting park. I could hardly contain my excitement.

Yet, my excitement was tainted by a very strange and disquieting thought – was there even a Pakistan to go back to?

My family and friends would be there, yes, and the house I grew up in, and my high school, and the neighborhood park, and the grocery store where my mother did the monthly shopping, and our favorite ice cream spot…

But what of the country? And I’m not talking about the poverty, and corruption, and crippling natural disasters – I’m talking about a place more sinister, much more frightening…

A place where two teenage boys can be beaten to death by a mob for a crime they didn’t commit, with passersby recording videos of the horrific scene on their cell phones…

A place where a woman can be sentenced to hang for something as equivocal as “blasphemy”…

A place where a governor can be assassinated because he defended the victim of an unjust law, and his killer hailed as a “hero” by religious extremists and educated lawyers alike…

This is not the Pakistan I know. This is not the Pakistan I grew up loving. This bigoted, bloodthirsty country is just as alien to me as it is to you.

The Pakistan I know was warm, bustling and infectious, like a big hug, a loud laugh – like chutney, bright and pungent, or sweet and tangy, like Anwar Ratol mangoes. It was generous. It was kind. It was the sort of place where a stranger would offer you his bed and himself sleep on the floor if you were a guest at his house; a place where every man, woman or child was assured a spot to rest and a plate of food at the local Sufi shrine. A place where leftovers were never tossed in the garbage, always given away, where tea flowed liked water and where a poor man could be a shoe-shiner one day, a balloon-seller the second, and a windshield-wiper the third, but there was always some work to do, some spontaneous job to be had, and so, he got by.

My Pakistan was a variegated puzzle – it was a middle-aged shopkeeper in shalwar kameez riding to work on his bicycle, a 10-year old boy selling roses at the curbside, a high-heeled woman with a transparent pink dupatta over her head tip-tapping to college, with a lanky, slick-haired, lovelorn teenager trailing behind her.

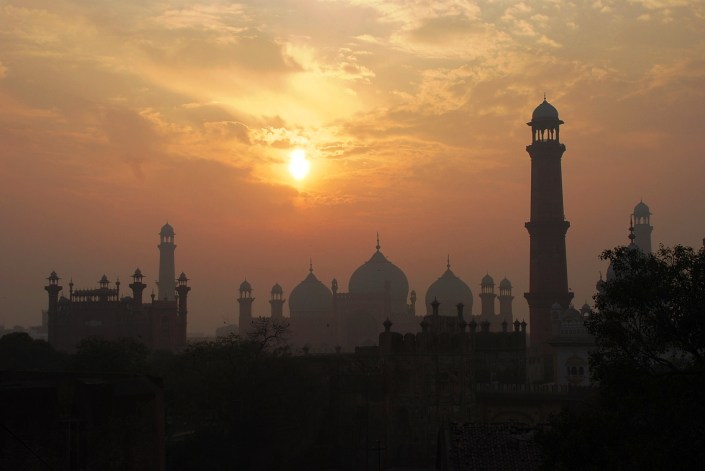

A Michael Jackson-lookalike doing pelvic thrusts at the traffic signals for five rupees, a drag queen chasing a group of truant schoolboys in khaki pants and white button-down shirts. Dimpled women with bangled arms and bulging handbags haggling with cloth vendors, jean-clad girls smoking sheesha at a sidewalk café, and serene old men in white prayer caps emerging from the neighborhood mosque, falling in step with the endless crowd as the minarets gleamed above with the last rays of the sun in the dusty orange Lahore sky.

My parents were practicing Muslims, and religion was always an important part of my life. Like most Pakistani children, my sister and I learnt our obligatory Arabic prayers at the age of 7; I kept my first Ramadan fast when I was 10, bolting out of bed before dawn for a sublime sehri of parathas, spicy omelettes, and jalebi soaked in milk. By the time I was 13, I had read the Holy Qur’an twice over in Arabic, with Marmduke Pickthall’s beautifully gilded English translation.

But beyond that – beyond and before the ritual, or maddhab, as they say in Sufism, came the deen, the heart, the spirit of religion, which my parents instilled in us almost vehemently, and which to me was the true message of Islam – compassion, honesty, dignity and respect for our fellow human beings, and for every living creature on the planet.

So, while we as Pakistanis had our differences, and practiced our faith with varying tenor – some were more “conservative” than others, some more “liberal”, some women did hijab while others didn’t, some never touched alcohol while others were “social drinkers” – we were all Muslim, and nobody had the right or authority to judge the other, no red-bearded cleric or ranting mullah. There were no Taliban or mullahs back then; if they existed, we never saw them. Not on TV, not in the newspapers, not on the streets, in posters or banners or fearsome processions.

It wasn’t a perfect society – far from it. Inequality and abuses were rampant, and daily life for a poor person could be unbearable. But they were the kind of problems that every young, developing, post-colonial nation faced, and the worst thing that could happen to you when you stepped out of the house was a petty mugging or a road accident, not a suicide blast. It was chaotic, but it was sane.

Then 9/11 happened, and society as my generation knew it began to unravel.

It started as a reaction to the U.S.-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and the “clandestine” war in Pakistan – a reaction shared by Pakistanis across the social spectrum. But somewhere along the way, the anger and grief mutated into a suicidal monster of hatred, robed in religion and rooted in General Zia’s pseudo-Islamic dictatorship of the 1980’s and the U.S.-funded Afghan jihad. Pakistan was engulfed by a frenzy, an unspeakable frustration, not only at the neighboring war that had expanded into its heartland, but at everything that was wrong with the country itself. And, like the hysteria that fueled the Crusades or the 17th-cenutry Salem witch-hunt, religion was the most convenient metaphor.

I don’t claim to understand it all, or be able to explain it. But what I do know is that, alongside the two purported targets of the “War on Terror”, there is no greater victim of 9/11 than America’s indispensable, ever-“loyal” ally and doormat, Pakistan itself.

Maybe I’m romanticizing a little. Maybe I’m being over-nostalgic about the past, and the Pakistan of my childhood. But that’s the only way I can retain some affection for my country, the only way I can sustain the desire to go back and live there – if I know and remember in my heart, that it has been better. That it was not always like this. That it was once rich, multifaceted, beautiful, tolerant, sane – and can be again.

Warmly Winter

Published in Pakistan’s “Women’s Own” Magazine, December 2010

It’s finally happened.

The knock on the door, and an outstretched palm containing a steaming plate of food.

Chicken-and-veggie rice casserole or Palestinian maqluba, to be specific, on a plastic white flower patterned plate.

Yes, Mama Jama the landlady brought us dinner!

And it couldn’t have been at a more opportune time. In my missionary zeal for bhoono-fying, I had just burnt the aloo gosht. Mama Jama probably smelt the aroma of charred onions drifting down the staircase and took pity on us.

Of course, it’s not that I was expecting her to. It’s not the reason I’d show up at her doorstep every other week with a lovingly-prepared bowl of kheer, zarda or melt-in-your-mouth gulaab jaaman.

I was just being neighbourly.

And testing out my (extremely novice) Pakistani dessert skills.

And skirting the guilt of single-handedly consuming 2 pounds of sugar in one afternoon – an inevitability if said bowl of kheer or gulaab jaman remained in my apartment, thanks to the relentless sweet tooth inherited from my dad.

Yes, I am an epicure (fancy word for greedy). If it were up to me, I’d either be at home baking apple pies and chewy chocolate brownies before proceeding to do justice to their goodness, or I’d be outside in a café or bakery sinking my teeth into the congenial warmth of freshly-baked cinnamon roll, red velvet cupcake, almond croissant, pumpkin pie, strawberry cheesecake, piping hot apple pie or chewy chocolate brownie, with my nose between an equally delicious New York Public Library book.

Luckily, I have a very active and health-conscious husband, who, a) makes sure that I never find more than 50 cents in my wallet at whatever random moment the sweet tooth calls, rendering me helpless in the face of heavenly-smelling street stalls and petite cafés with bothersome minimum-cash policy; and, b), manages to drag me out somewhat regularly for a bit of exercise.

Our current physical activity is rock climbing – on the boulders of Central Park. So, if you ever happen to be strolling near Columbus Circle on a Saturday morning and see two figures attached to a rock – one, strong, athletic, moving swiftly across the rock face like a demo picture from “The Self-Coached Climber”, and the other a ball of play-dough smushed against the wall – you’ll know it’s us.

I have to say though, as much as I was dreading another East Coast winter, there is a charm about it, a crisp-coloured storybook charm.

I don’t know if it’s in my brown BearPaw boots, or the toasty knit cap and woollen mitts that I gleefully don every morning; the feel of a hot Starbucks hazelnut latté between my fingers or the beautiful bareness of Central Park, the crunch of leaves beneath my feet, and the blossoming of Christmas lights on 5th Avenue. Ice skating at Bryant Park, followed by a cup of steaming apple cider and a stroll through the dazzling holiday market, a veritable Santa’s workshop; the pleasant conviviality of huddling with strangers in the 8×8 floor space of Kathi Rolls or Mamoun’s Falafel in the Village, exchanging smiles over a shami kabab roll and shared hearth; or, maybe it’s just the indescribable comfort of home, where you return from the cold with relief and bliss in your heart – given that the heat is working, which you can trust it to be if you’re on food-exchange terms with the landlady.

Of course, slopping through puddles to do your laundry or buy a carton of milk is another matter, as are the thundering hailstorms that sound as if they’ll break straight through your skylight and flood the apartment, the sodden subways and the razor-sharp winds whipping through the labyrinth of high-rises ready to slice off your nose, or having to wear the same inflated down jacket for five months until you are resigned to looking like the Michelin Tyre Man in every photograph.

But no matter how much I complain about it now, winter was always my favourite season in Lahore. I would dream about it the whole year – dream of the day, sometime in November, when the gas heaters were unearthed from the store room and dusted out, when bright chunky sweaters and printed Aurega shawls were unpacked and sunned to get rid of the minty smell of mothballs.

The marvelous halvas my mother would begin to ghot-ofy in the kitchen, gajar, anda, sooji, and my personal weakness, chana daal, the rich smell of ghee and shakkar permeating the entire house in its intoxication; the blood-red pomegranates and succulent oranges we’d eat sitting out on the dewy lawn, the dogs snoozing under the chairs, wrapped up in a brown khaddar shawl that smelt of faded Chanel No. 5.

Even going to LUMS in the morning was fun, dressed in a gigantic sweatshirt and sitting on the sidewalk across the cafeteria after class, watching the steam from the PDC teacup mingle with our cloudy breaths, as the fabled Defence fogs circled in around us from the empty stretches of Phase 5, and we pretended we were in a Sci-Fi movie…

Winter was synonymous with Ramzaan and Eid, with grand tented shaadis, Capri nashtas and apple sheesha at MiniGolf, starry walks, sunny picnics, bonfire dances; lying curled up on a floor cushion in front of the heater in your living room, looking out at the lights of the 600-year old Lahore Fort from the rooftop of Cuckoo’s on your cousin’s December birthday, or blushingly saying “Hello” to your soul mate in the back rows of a Gymkhana concert…life didn’t get any better than a winter in Lahore.

And though I am here now, and New York City beckons with its lights, treats and newfound friends, and I am happy with my new life, I still dream of those magical Lahore winters, old friends, old shawls, ancient forts, and the fresh, pink-cheeked days that hold some of my most precious memories …

And that’s alright. Because time doesn’t flow if you don’t dream.

California Dreaming

Published in Pakistan’s “Women’s Own” Magazine, November 2010

I’m sitting on a Virgin America flight to San Francisco, sandwiched between two very distinct gentlemen: one, a rotund avuncular specimen happily cuddled into a hot pink inflatable pillow, and the other a goggle-eyed, fuzzy-lipped stick figure equally absorbed in a game of Doom on his personal TV.

Meanwhile, I’ve been nibbling on the egg and cheese Panini I bought from JFK five hours ago. Consider yourself lucky if you even get a complimentary packet of peanuts on a domestic U.S. flight; the crisp coleslaw sandwiches and squelchy shahi tukray of PIA en route to Karachi are but a distant fantasy. Ah, PIA, I forgive you the screeching babies and leering uncles and assiduously obnoxious 5-year olds kicking behind my seat for the sake of those shahi tukray!

There it is again – that incorrigible nostalgia I’ve been wallowing in of late. It also happens to be the sole motivation behind this trip to the West Coast. San Francisco, Berkeley, Bay Area! What don’t I miss about that place? The deep blue waters of the Bay, the impossibly puffy white clouds, the crunchy-freshness of the air, the swaying palms on the horizon? Or the incredible purple-gold sunsets over the Golden Gate Bridge, which I watched from the steps of the International House in Berkeley every evening on my way back from class…

Then there were my favourite haunts – the thrift clothing stores where you could find tassled Pocahontas skirts, Dashikis and BCBG jackets all on the same rack, Berkeley’s answer to Zainab Market and the place I’d inevitably splurge half my work-study paycheck. Those wondrous second-hand book stores, musty and chaotic, where wiry old men in suspenders smiled benignly at you over their wire-rim glasses, exactly the kind you’d expect to hand you a copy of “The Neverending Story” and promptly vanish. The board game shop that I never spent less than an hour in each time I entered.

The diminutive Taiwanese baba in a coolie hat who stood on a bucket all day chanting “Happy, Happy, Happy” and holding anti-Bush and anti-Dalai Lama placards; the crazy campus bum who earned his daily bread by charging people to swear at him (I think the rate was a dollar per minute). The roadside jewellery stalls on Telegraph Avenue, a riot of feathers, seashells and antique Afghan silver; the proliferation of Pakistani fast-food joints, free Lipton mixed chai and plastic cups of kheer; the refreshing absence of chain stores till as far as the eye could see, save for the errant downtown Starbucks. The fixture of anti-war protestors on Sproul Plaza, the Native American chief who lived in the trees and ran for Berkeley mayor, the weedy-smelling People’s Park and my homeless old Vietnam-veteran friends who strummed away my favorite Eagles’ songs on the grafittied pavements.

Crazy, beautiful, bubble-of-a-Berkeley, just my kind of place. But most unforgettable of all were the friendships, forged over the unforgettably tasteless food they served at the International House, where I lived two years during Journalism School.

So, when I found out that Z’s company was sending him to Los Angeles for work, I immediately pulled out my old Dashikis and peasant tops and gotay-wali kurtis from the suitcase under the bed – no way was I missing out on a trip to California either!

As for New York City – well, I’m learning to like it. Getting out of the house definitely helps, which can be quite a challenge for a ghar ghussoo or homebody like me. As I blissfully look around at the avocado green walls of my apartment, the potted Pothos plant hanging from the ceiling, the block-print Gultex tablecloth, the beauteous kilm gracing the dark brown floor of the living room, which my mother brought over from Lahore this summer, the mantelpiece full of books, and as I inhale the scent of caramel-vanilla candles and sandalwood incense, listen to the birds chirping in the trees, and open my fridge to admire the lasagna, apple pie, leftover homemade Pad Thai and housewarming chocolate pastries, I think: who in their right mind would want to step out of this piece of heaven? Out there, into the puddles and gloom, odiferous subways and tourist-yapping streets?

Actually, I have been forced to step out. I have been forced to communicate with people other than my husband, the Palestinian landlady and the Indian-Guyanese cashier at the grocery store – courtesy my two jobs.

Yes, I’m working! The hitherto unemployed, Master’s degree-holding housewife has found not one, but two jobs (Thank you, thank you). I have joined the ranks of the active labour force. Now I too get to catch the morning train at rush hour along with the rest of the dapper designer bag-clutching Stieg Larsson-obsessed populace. I, too, grumpily slam down the alarm clock at 7 a.m., gulp down a bowl of cereal, throw on a slightly crumpled H&M button-down, and shoot down the stairs to the subway with the alacrity of somebody who’s just been informed that Michael Jackson has come back to life – all to sit in a windowless office staring at a computer screen for 8 hours straight, with a meager 15 minutes at lunchtime to eat your humble turkey sandwich, and, if it’s a particularly exciting day, exchange a few words other than the mechanical “Good Morning” with your ambitiously poker-faced colleagues.

Sounds tempting, doesn’t it? It’s true, jobs are overrated. Work is overrated. A necessary evil. At least that’s what I’ve concluded from my weeks of face-reading and eavesdropping on the jam-packed subways, and from my own (brief) brush with a 40-hour work week. I’m already beginning to daydream about the “Era of Gainful Unemployment”: extended tea sessions with Mama Jama the landlady over half-a-dozen wedding albums and Syrian soap operas, 5-hour long grocery store binges, simultaneously reading Kafka, Tolstoy and Orhan Pamuk, walking with no purpose. The “Era of Frustrated Unemployment” has been conveniently glossed over, like a Pak Studies History book, as has the even more miserable “Job Application Process”. Dissatisfaction, thy name is me! Of course, it would be an entirely different matter, if, say, I actually found that elusive “dream job”, or, if I even knew what that was…

“Ladies and Gentlemen, we have begun our descent into San Francisco International Airport. Please switch off all electronic devices, bring your seat backs to an upright position…”

Yay! The announcement I’ve been waiting for! Peering over the globular uncle’s hot pink pillow, I catch a glimpse of the blue water, the green hills, the red arches of the Golden Gate from the window. Memories flood back to me. I remember the moment when, over 3 years ago, I landed in this city as a graduate student, straight out of LUMS, moving away for the first time from the only home I had ever known. I remember teasing my mother at the forlorn finality of her goodbyes – “Ammi, I’m going to come back, you know!” But she knew better.

And though I can’t wait to see all the places and people I loved, the nooks and crannies and eccentricities of this place I grew to call my second home, I also feel a little nervous. Will it be the same?

I often feel this way landing in Lahore. Is going back ever the same? Or do those beloved places and people inevitably move on, and leave you behind, so that the only way you can enjoy them is through nostalgia, through memory?

Perhaps they don’t change at all. Perhaps the change is in you.

PS: I had an absolutely fabulous time in California. Can’t wait to go again.

PPS: In case you were wondering, the beady-eyed furry creature(s) in the oven have been eliminated.

Scents of Ithaca

I woke up this morning with the smell of damp earth and wild flowers tickling my nose. I imagined I was in my room in Lahore, lying on that beautiful Sindhi-tiled rosewood bed my dad had unearthed from some curio shop in Karachi, the plum-coloured curtains flapping in the breeze and the jaamun tree outside my window bristling with dew. There would be halwa puri and aaloo cholay for breakfast downstairs, and Ammi Abbu would be sitting eating sliced oranges with chaat masala in the front lawn reading the Sunday paper, with our two Alaskan huskies Sabre and Tara gracefully curled at their feet…

I rubbed my eyes. No, I wasn’t in Lahore. I was in our apartment in Ithaca. But outside, it could’ve been Lahore, on a rain-fresh, life-affirming November day. “I’m going for a run,” I announced, a newfound interest since my high school track champ husband Z bought me a pair of purple Nike running shoes for my birthday.

As we jogged along on the clean wet pavements, wind rustling in the oaks and maples overhead, purple tulips and yellow daffodils nodding in their beds below, past the shingled cottages, blue, pink, red and white, and in the distance, the rolling hills of Cornell, silhouetted dark green against a steel blue sky, I breathed in the cool, redolent air and thought, “Ithaca really is beautiful. I’m going to miss this place”.

I wouldn’t have said that nine months ago. Soon after we moved to Ithaca last Fall, and Z settled into his school routine, leaving for class every morning at 8 and returning at 6 in the evening, I found myself a prisoner in our apartment: tinkering around in the kitchen, vacuuming and re-vacuuming the bedroom, re-arranging the cushions on the sofa, trying to decide what to make for dinner…Days, sometimes weeks went by when he was the only person I talked to face-to-face.

I felt frustrated – and I was annoyed at myself for being frustrated. But it couldn’t be helped. How many books could you read, how many BBC miniseries could you watch, how excited could you possibly be about cooking when you had to do it everyday? The fact was, I had never been the “domestic” or ghareiloo kind – though I had imagined I would be if given the opportunity – and never in my life had I been so unoccupied, so uncomfortably free. Till now, every moment had been replete with people, parents, sister, cousins, aunts, uncles, friends, teachers, classmates – something to do, somewhere to be, something due, something planned, someone to talk to. I had even complained about it sometimes – Oh, I wish I had more time to myself! – and now that I had that time, I didn’t know what to do with it.

I blamed Ithaca. Dull, boring place. No jobs to be had, no friends to be found, no sign of life after 7 p.m., sub-zero temperatures 3/4ths of the year, nearest grocery store a 40 minute bus ride away on a bus that came every hour… How was one to live in such a place? Weeks of job-hunting and CV-submitting turned up nothing – even the local Barnes & Noble never got back to me. I was so mad I vowed to defect to Borders. “They probably thought you were over-qualified,” said Z to comfort me.

But I wasn’t comforted. Innumerable possibilities crowded my mind as I sat daydreaming in my red arm chair, of New York City, of the Bay Area, of Lahore, of what I might have achieved had I been there, of what I might have made of myself. Oh, what if?…

That was nine months ago. Z is about to graduate now, and our move to the big city is just weeks away – the start of our new life, on our own feet, the excitement, the rush of people on the street, the plays and the concerts, that dream job, glowing above in the neversleeping neon ether…

I’m excited. But more than that, I am at peace, because I understand now what I achieved in Ithaca, what I found – something more precious and infinitely more satisfying than any job could have been.

I found two friends, Elsa and Silvano. The moment we met, at the door of our apartment, where the landlord and local godfather Carl Carpenter had brought them in his cherry-red pickup, the “nice Mexican couple” who had just got into town and were looking for a place to live, I knew we were kindred spirits. It was the kind, laughing eyes, the ready smile, the same room at the Hillside Inn. We could talk about books and movies, music, religion, ideas and dreams for hours on end, till we’d look up and see the empty restaurant tables and anxious faces of the waiters, and cry out, “What, it’s been four hours already?” We laughed at the same jokes, took immense pleasure in “Big Brother”-bashing, reveling in our non-Americanness, whispering animatedly of conspiracies and capitalism lest the identical blond-beefy-biker family sitting next to us at the food court overheard. The Beatles, Dracula, Scorcese, 1984, Pictionary, Canon cameras and 5K runs, achari chicken and tostadas, Tampico and Lahore, Urdu and Spanish…it all seemed one. Urdu and Turkish, too, and aromatic tea from a petite hand-painted glass cup, cranberry muffins and Turkish delight, bangles and Rekha and two adorable two-years olds in shalwar kameez with cake on their face. Alev, Demir and the twins, my Ithaca family. It began with an email, a response to a Craigslist ad, my first freelance video-editing gig; turned into Urdu lessons and babysitting, playing with puzzles and building blocks, cushiony footballs and cars, singing “Lakri ki Kathi” and “Chanda Sooraj Laakhon Taare”; ended with sisterhood. They threw me a party on my birthday, a beautiful picnic in the park, gifted me their comfylicious Papasan, just because I had once said in passing that I liked it. I was overwhelmed by their affection; I felt I had left some mark on their lives, as they had on mine, found a relationship that would last. Could I have said the same about proof-reading papers for the Cornell Astronomical Society, cashiering at Barnes & Noble? When one of the Taiwanese students I tutor got an A on a final paper I edited, or the Chinese visiting scholar’s request for an interview with a D.C. official was finally accepted, with the help I’d given him in his letter, and they said to me with endearing directness, “We are so lucky to have you” – how could I have underrated that feeling, that sentiment, that satisfaction?

We came back from the run, and I made spicy baked eggs for breakfast, one of beautiful Shayma’s wonderful recipes. My husband did the dishes while I read aloud a chapter from “Brave New World”, Elsa and Silvano’s birthday gift to me and sequel to our recent Orwell craze. Afterwards we sat listening to George Harrison on Pandora while Z worked on a presentation and I wrote this post, with the doors wide open and the smells of spring enveloping our little one-bedroom house, evoking memories of different times and places, mingling past with present.

When in America, do as the Americans don’t

I wrote this piece for a class on Immigration Reporting at Journalism School last March, right before I left for Spain to film a short documentary about Pakistani immigrants in Barcelona.

Identity is such a fluid thing – parts of it change every time you move, make new friends, do something different in life – and parts of it are simply unalterable. I can’t say I feel exactly the same now as I did when I wrote this, but it was a very strange and interesting part of my life, shared I think by many Pakistanis studying or living abroad.

Published in The Express Tribune Blog, August 25th 2010

___________________________________________________________________________________

Rediscovering nationality in the melting pot

MANAL AHMAD, PAKISTAN: I was spring-cleaning my laptop a few days ago when I came across these two pictures. Normally, I wouldn’t have even noticed them, buried in virtual stack-loads on my hard drive, the blessing and bane of digital photography. But, my general sense of awareness about “culture” and “identity” somewhat heightened of late, I paused to look, and was struck by the utter incongruity of it all. Not just the photographs, but of myself – in Pakistan, an English-sprouting, skinny-jean-wearing junk-food-eating, American Idol-watching “Westerner”, and in America, a jingly, jangly, Urdu-priding, chai-chugging, public transport-taking “Pakistani”.

I moved to California from Pakistan in 2007 to start graduate school at UC Berkeley. Though I had come as a student, I experienced much of what a new immigrant experiences – curiosity, bewilderment, loneliness, discrimination, independence, and – unexpectedly enough – a conscious need to re-affirm my “identity”. During the 22 years I lived in Pakistan, this had only occurred to me on a handful of occasions – cricket matches against India, for example, or when the enormous green-and-white flags appeared on 14th August, Independence Day, only to disappear a day later.

At the upper-class, English-medium, private university in Lahore I attended for my Bachelor’s, there was a course called “Pakistan Studies: Culture & Heritage” that we were required to take before graduating. Ironically, it is in this class that we were thoroughly “de-nationalized”. In this class, taught by a radical Marxist Yale-educated professor, we learnt there was no such thing as a “Pakistani”.

Then what was Pakistan? Little more than a project of India’s Muslim intellectuals, feudal elite and the British colonial government. The very concept of “nation-state” was foreign to the Indian subcontinent; it was forced upon us by the British, and Pakistan was the direct result. At independence in 1947, less than 10% of the people in Pakistan actually spoke Urdu, the national language; most spoke regional languages like Punjabi, Sindhi, or – Bengali! Yes, because Bangladesh used to be a part of Pakistan, until it seceded in 1971, which of course didn’t do much for consolidating our national identity.

Add to that the fact of the vast economic disparity in the country, 6th most populous in the world, where 1/4th of the people live below the poverty line and 54% have no basic education – I, who started learning English at age 4 and grew up watching Disney cartoons, had a computer at home ever since I can remember, ate out with friends every weekend at American Pizza Huts dressed in jeans and cute tops because that’s what was cool and shalwar kameez was something only our mothers wore or we kept for formal occasions – I was obviously the exception.

That is not to say I didn’t enjoy my culture, as I knew it. I loved it, yes; I loved my traditional embroidery, the block-print and mirror-work, the silver jewelry. I loved my home-cooked food, the grand weddings, the Mughal architecture, Ramadan and Eid, sufi-rock; but I loved it, like a visitor, like a curious traveler, collecting souvenirs, taking pictures. Pakistan was a colorful, exotic TV series, which I could switch on whenever I wanted, and switch off whenever the beggars and child laborers and hungry people came on.

My world was very different. Did I really know anything beyond it? No.

Then, I came to America, the place where what little “nationality” I had might have melted away completely. But quite the opposite happened.

I remember the funny warm feeling I got when I saw the first restaurant sign that said “Pakistani cuisine” in Berkeley (later to discover that desi or South Asian food was a local favorite and that there were hundreds of such restaurants all over the Bay Area). “Hey, that’s my place!” I would think with pride, and proudly order in Urdu, and tell him to make it extra spicy, because of course that’s what I was used to. I would stare at the food, my food, that all these foreigners, these Americans seemed to enjoy so much, mystified at the sight of them eating with their hands, tearing the naan into morsels and scooping up the bhindi or aaloo gobi – food so utterly commonplace that you couldn’t find it at even a roadside stall back in Lahore.

I felt a surge of joy at taxi rides, when I would invariably get a Pakistani or Indian driver (yes, Indian counted too, but that’s another complex affinity, another story). I would invariably smile at any man or woman I passed who looked desi to me – maybe I would talk to them at the bus stop or in a store – and how thrilled I was if they understood Urdu!

Perhaps the most bizarre thing was paying $20 to dance bhangra at a San Francisco club called “Rickshaw Stop”. A bhangra club? That didn’t make any sense! Bhangra was what guys did. They did it at weddings to live drummers, or in Punjabi music videos, or in the villages. You didn’t dance bhangra for any other reason. And how would a girl dance bhangra in the first place? Why would you ever even need a lesson in bhangra? It was all too confusing.

But when I saw what it was all about, I realized with a start: this was as much foreign to me as to everyone else in that room. This was bhangra? This incredible complicated sweaty aerobic choreographed performance that all these goras (literally, “white people”, but meaning any Westerner) seemed to be enjoying out of their minds?

Well, I decided I wanted in – I decided that this was mine, it was mine to own, it was Pakistani, and I could do it better than any of these goras because this is what we did back in Pakistan, didn’t we? And everyone believed me.

Why did I need to re-affirm my difference, my uniqueness, my identity in the melting pot? Why did I feel more Pakistani in America? I don’t really know. Is it because in this country, “ethnicness” is generally prized, coveted, glorified? Or, as a human being, you struggle to identify with a group because you find strength in groups, so you meet, talk to and befriend people you may never even have acknowledged back home – just for the color of their passport? Is that hypocrisy?

In Pakistan, I would never talk to my cab driver. I’ve never dream of taking a cab in Pakistan by myself. But here – it is a bonding experience. Here, I trust a desi cab driver over all others. He might have been a criminal back home, for all I know. But in America, it doesn’t matter. We are the same.

And sometimes I find myself thinking – if all Pakistanis moved to the U.S., we might actually be a nation – a much better nation! We would work hard, we wouldn’t have to bribe or take bribes to make our way in life, and we could communicate with each other, without suspicion or pretense or awkward social barriers.

But the question is, is it even real? Or do we find this strange affinity only because we stereotype ourselves to fit American expectations and tastes, shaking hands and serving them chicken tikka masala while pretending its “authentic”?

The last vestige of nationality probably lies in the accent. The moment people stop asking you what part of the world you’re from when you talk to them – you’re lost. You’ve become American. You drop your T’s. You’ve successfully “assimilated”. And for this confused “Westernized” desi, for whatever illogical irrational reason, that’s not a compliment.

Lahore’s Old City

As this is my first post, it seems fitting to dedicate it to Lahore, my beautiful hometown. I haven’t lived there for 3 years now, so I’m aware that much of my nostalgia is tinted. But what does it matter? Lahore will hold endless fascination and mystery for me, if only in my imagination. This is a “brief” history of Lahore’s inner city, the “Androon Shehr” in Urdu, that I wrote as part of my thesis at college, with my cousin and constant companion Sana. Here is an excerpt, minus the footnotes! Any additional lore, fact or fiction about Lahore is welcome :) You may also want to read Chowk: Musings at a Crossroads.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

“Lahore of blissful waters, be praised

The goal of old and young, Lahore

I do not think that in the seven climes

A place so lustrous exists, as Lahore.”

– Talib-i Amuli, Ghaznavid poet

Hindu legend has it that, nearly three millennia ago, Loh, one of the sons of the god Rama, hero-king of the epic “Ramayana”, founded a city on the banks of the river Ravi. He called the city Loh-Awar – “The Fort of Loh” in Sanskrit. Situated on a naturally elevated alluvial plain at the gateway between the mountains of Kashmir and waters of the Indus, Loh could not have chosen a more scenic or strategic location for his city. Today, we know Loh-Awar by one of the numerous variants of its name that survived: Lahore.

The original site of Lahore, believed to have existed somewhere in the foundations of the Lahore Fort, is now found only in myth and imagination. However, historical evidence suggests that the “core” of the city, what is known colloquially as the Androon Shehr, assumed its present shape and form in the aftermath of the Ghaznavid invasion in the 11th century. Hitherto a mysteriously abandoned Hindu principality, the city underwent a veritable transformation at the able hands of Malik Ayaz, governor of Lahore under Mahmud of Ghazna. It is said that Malik Ayaz built up the walls and gates of the city in one miraculous night; whether or not that is true, Lahore, the capital of Mahmud’s Indian provinces, soon grew to rival the city of Ghazna itself as a centre of wealth, learning and culture.

Lahore suffered many reversals of fortune in the ensuing centuries, the inevitable target of countless invaders, plunderers and would-be kings – from the Ghauris to the Mongols, Taimur the Lame to Bahlul Lodhi – owing this fate both to its geographical location and to the stories of its splendour. However, it was not until 1526, when a certain Taimurid prince from Ferghana decided too to try his luck in the plains of the Punjab, that Lahore regained the status and security it had enjoyed in Ghaznavid times. That young prince was Babar, the first Mughal emperor, and his dynasty, firmly anchored in its North Indian strongholds, had come to sta y.

Thus the city of Lahore, together with Delhi and Agra, witnessed the apogee of its career under Mughal patronage. Merchants, scholars, musicians, lovers, travellers from both ends of Eurasia, thronged its narrow streets; Eastern and Western poets alike eulogized the city for its “palaces, domes and gilded minarets”, for the “enchantment” locked within the burnt-bricks of its miraculous walls. In 1584, the Emperor Akbar shifted his royal residence to Lahore, renovating the Fort, constructing nine guzars (residential quarters) within the city, and rebuilding its walls and gates. His son Jahangir, likewise, continued the legacy of the sponsorship of arts and architecture in the city of his birth; English visitors to Lahore, especially frequent since Jahangir granted trading rights to the East India Company in the early 17th century, described it as “a goodly great city, one of the fairest and most ancient of India, exceeding Constantinople itself in greatness”. But it is Jahangir’s son, Shah Jahan, who earned for himself the repute of greatest of Mughal emperors, at least in terms of wealth and architectural opulence. Under Shah Jahan, Lahore glittered and flourished like never before: “a handsome and well-ordered city”, “crammed with foreigners and rich merchants” and “abundant in provisions”, in the words of Niccolo Manucci, an Italian physician serving at the Lahore court in Shah Jahan’s reign. The Wazir Khan Mosque, Shish Mahal (“Palace of Mirrors”, within the Lahore Fort) and Shahi Hamam (“Royal Bath”) in the Walled City, as well as the Shalimar Gardens in the suburbs, are but a few remaining testaments of the prosperity of the age, while the Taj Mahal in Agra has acquired iconic status.

Yet, already in Shah Jahan’s lifetime, Mughal coffers had begun to shrink, and the reign of his younger son Aurangzeb, last of the great Mughal emperors and builder of the Badshahi Mosque, was plagued with all the uncertainty and instability of a dynasty running the final pages of its history. With the death of Aurangzeb, Lahore, like the remaining parts of the Indian subcontinent still outside the control of British traders and self-styled governors, fell victim to the cruel vicissitudes of politics. The relentless raiding of the Afghan Ahmad Shah Durrani, and later Shah Zaman, and their furious battles with the Sikhs over the sovereignty of Lahore left the city permanently scarred. When the Sikh forces, led by Ranjit Singh, ultimately took power in 1797, they inherited a desolate township with crumbling walls, which they proceeded to loot and destroy, so that in 1809, an English officer described Lahore as “a melancholy picture of fallen splendour, of which now only the ruins are visible.”

But Lahore saw the beginning of the most damaging phase of its history in 1849, when the British purchased the province of Punjab from the incumbent Sikh Maharaja. The colonial authorities did not loot or plunder the Inner City as previous invaders had; they Orientalised it. While they did engage in major renovation projects in the Inner City, repairing portions of the Lahore Fort, Badshahi Mosque and other buildings destroyed by the Sikhs, their efforts were centred upon the development of the Civil Lines and Cantonments, which lay beyond the perimeter of the Walls. Suddenly, the Inner City became synonymous with the “Old City”. Invisible barriers were erected between “native” space, symbolized by the crowded, “quaint” streets of the Androon Shehr, and the manicured, tree-lined “colonially produced” space without– the origins of dualism, the modern-traditional dichotomy that prevails in postcolonial cities to this day.

Numerous crafts and trades, associated with and sustained by the demands of a royal court (Ghaznavid, Mughal and Sikh), met their inevitable demise with the British interlude – for example, the manufacture of elaborately wrought weaponry. Other court-related skills, such as miniature painting and fresco-work, were stripped of their former utility and relegated to the status of antiquated “arts”, fit to be practiced in Art Schools alone. Yet others, such as gold embroidery, silk-weaving and brass- and copper-smithing, continued to persist, though they catered to a diminishing “inside” population, relative to the rapid settlement of “outside” areas by colonials and indigenous nouveau riche. At the same time, the British initiated an irreversible process of change within the Androon Shehr, especially through the act of removing much of the old walls of the city as a precautionary measure against urban revolt, which became a genuine threat in the years following the Mutiny, or War of Independence, in 1857.

On the eve of decolonization, the Androon Shehr was still considered a prestigious, if not an affluent area, the cosmopolitan home of Lahore’s old, well-established families, of upper-class literati, bourgeois merchants and vagabonds alike. But Partition violence, concentrated in the border cities of the Radcliffe Award, devastated the fabric of the Androon Shehr’s society on an unparalleled scale; “The Walled City was shaken to its foundations”. The inhabitants of the Shehr, riled by communal hatred, wreaked havoc upon their own city – the gates were vandalized, bazaars were burnt, and entire neighbourhoods razed to the ground. Depopulation of the religious enclaves, coupled with the waves of migrants from across the border, turned Lahore into a rootless city of ruffians and refugees. From this massive convulsion, the Androon Shehr never truly recovered. It was the point of no return.

It was also the point of new beginnings. In the freshly conceived country of Pakistan, Lahore retained its age-old position as capital of the Punjab, yet the intensive redevelopment work that followed, under the auspices of the Lahore Improvement Trust (LIT), did not aim to “preserve” what was left behind. It aimed to remake. The debris was levelled clean by bulldozers, the narrow streets giving way to large thoroughfares and new markets, with little or no consideration to the surrounding architecture. Yet, in what seems an ironic or perhaps expected sequel to colonial activities, Lahore resumed to expand outwards, with the LIT concentrating its construction efforts upon areas such as the Civil Lines, and the new suburban communities of Model Town, Gulberg, G.O.R., Mayo Gardens and so on.

Meanwhile, the Androon Shehr was left to its own devices, and change was inevitable, though difficult to define. The Shehr was not impervious to the contemporary forms of modernization enveloping the surrounding city, yet, up till 1979, more than 80% of its built stock still comprised of Mughal structures, and most of the Lahore Development Authority’s public and municipal development programs continued to focus on the newer parts of the city.

Today, the Androon Shehr, as a physical space, is a mass of old, beautiful, rotting buildings and dusty, twisting streets, with choked gutters, unreliable water supply and precarious housing – home to “over a quarter of a million people, the largest concentration of urban poor in the country”. The government as well as academia profess to take keen interest in “arresting the decay of the city to preserve the nation’s heritage”, but the superficiality of their claims is borne out by observing the ground reality in the Shehr itself. The prominent monuments within the Shehr, mainly the Fort, tombs and older mosques, are repeatedly made the targets of much-advertised “historical conservation” and tourism campaigns, while the inhabitants of the City themselves, their lives and grievances, are conveniently overlooked in the media and other popular discourse.

It seems, in another ironic sequel to colonial Orientalism, that, for the people living “outside”, the Walled City exists solely for its historical value, a “suspended” site where only “traditional” time and place must be celebrated; the inexorable transformations taking place within the Shehr are altogether ignored. As it happens, however, the reality of the Androon Shehr differs sharply from the intentions to propel it as “a museum and relic of past glory”.

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2