Society

Farewell, fond 20s! I’m ready to move on

Why do we expect so much of life, and of ourselves? Why do we choose to be unhappy? Some questions pondered, some lessons learnt, some wisdom received

Published in Dawn Blogs, May 26th 2015

Once, when I was an undergraduate at LUMS in Pakistan, we were asked to create “future” CVs for ourselves, imagining where we would be 10 years down the road. According to my calculations, by age 30 I would be an acclaimed international affairs correspondent with Al Jazeera TV. I would also be a certified yoga instructor, the author of an award-winning collection of short stories, and the co-director of a charity school in Pakistan. I would have trekked to the base camp of an 8,000-meter peak (if not summited the peak itself), and I’d be speaking 5 languages like a native, or as we say in Urdu, farr farr.

A few weeks ago, I celebrated my 30th birthday. And looking back at that smug, overambitious piece of paper (I still have a copy), what do you suppose I felt? Disappointment, at falling short on pretty much all of my grandiose goals? Guilt, for being lazy, for not doing “enough”, for not “living up to my potential”? Anger, at myself, at people around me, at the circumstances that thwarted my legendary ascent to that 8,000-meter peak and to age 30?

No. I only laughed! Frankly, I couldn’t give a baboon’s butt about goals, objectives, achievements that you could enumerate on a CV, that you could neatly check off from a “bucket list” and be done with. I didn’t care about what I may have expected from life 10 years ago, 5 years ago, even 1 year ago.

I used to care, I used to care a lot. During my 20s, I was beleaguered by that pervasive pressure to “achieve”, all too familiar to us Millennials. Often times, we weren’t even sure of what we wanted to achieve; it could be an important position at a multinational corporation or a big bank, it could be starting our own business, running an NGO, getting a PhD, “making a difference”. Yes, what we wanted most of all was to make a difference, to “change the world”.

I am not a superhero!

I stopped thinking like that some time ago, and it was a conscious decision. I stopped thinking that I could change the world.

That’s not to say that I became cynical. I just realized that I, as one individual, did not have the power to change or “save” the world. I couldn’t eradicate poverty. I couldn’t stop wars. I couldn’t ensure that every child on the street went to school, that no woman was raped by any man. I couldn’t put an end to meaningless violence, I couldn’t reverse global warming.

I couldn’t carry through any of this in my own hometown Lahore, let alone the entire world. The world was chockfull of problems, had always been, and would always be. It was the sorry fate of humankind. And to think that you were somehow “special”, that you could clean up a mess that was centuries, millenia in the making just like you’d solve a nifty Math problem, was downright arrogant.

I couldn’t carry through any of this in my own hometown Lahore, let alone the entire world. The world was chockfull of problems, had always been, and would always be. It was the sorry fate of humankind. And to think that you were somehow “special”, that you could clean up a mess that was centuries, millenia in the making just like you’d solve a nifty Math problem, was downright arrogant.

Once in a while, perhaps once in every generation, somebody exceptional came along. Extraordinary people who, by dint of birth, effort, circumstance, and some serendipitous conjunction of the stars, did extraordinary things. The world’s heroes and heroines, revolutionaries and prophets, thinkers and humanitarians, inventors and scientists, artists and writers, whose names we all read in history books. I don’t suppose that any of these great people ever planned on changing the world, or becoming famous. I don’t suppose they wrote about it in their college applications, or scribbled it on their “bucket lists”.

I think they were just going about their lives, one day at a time, doing whatever it was they loved and believed in – not expecting any accolades or honors, not preoccupying themselves too much with “results”, just following their intuition, being themselves.

That’s one thing we all have the power to do; be ourselves. Improve ourselves, and consequently, have a positive effect on everything around us.

It could be something as simple as, say, recycling your trash. Giving a sandwich to the homeless man on your street. Holding open the door for an old lady at the metro station. Lending an ear to a friend who’s had a bad day. Giving somebody an unexpected gift. Teaching somebody a skill, or learning something new yourself. Making friends with somebody from a different religion, ethnicity, culture and country. Making the world a more tolerant, a more peaceful, kinder and happier place by embodying those qualities in your own person.

That was, realistically, the best I could do, and it was enough for me. There was no point in beating yourself up over “failed” ambitions or irrational expectations, neither your own nor those of others.

I am not a martyr or a saint!

The expectations of others, or “What will people think!”. We’ve all been oppressed by them – from something as trivial as buying the “right” gift for a birthday party, “having” to attend a cousin’s friend’s brother’s wedding or wearing the “right” outfit to a family lunch, to being emotionally coerced into a marriage by your parents, putting up with an abusive husband, sticking with a job that daily sucks the life out of you. Why? Because that’s what you’re expected to do. That’s what a good, responsible, respectable man or woman does. A good, responsible, respectable person makes everybody happy – everybody except himself. A good person is a martyr.

Now, there may be people out there who would gladly suffer all these societal tortures, and many more, out of a genuine sense of duty, or out of pure selflessness. But most of us are not like that. We are not selfless. We are not saints. We may like to think we are, but deep down inside, where nobody can hear our true thoughts, we ask ourselves: “Why am I doing this? Is it worth it? I’m fulfilling all my ‘duties’, but why am I still so miserable?”

There’s something perversely romantic about misery, the notion of sacrificing your life for the sake of others, for your children, parents, friends, your community and country, without a thought to your own wishes and desires. Whether or not you enjoy being cast in that role, society will definitely love you for it.

On the other hand, society will not take kindly to seeing you happy. That’s just shameless. And, if you insist on being so brazenly optimistic, then at least pretend to have something to gripe about!

This kind of thinking is typical among desis (South Asians), and I was done with it. If your actions didn’t spring from love or genuine kindness, if your only motivation was to “live up to” some vague ideal or ill-conceived expectation, the fear of what people might say, then those actions were worth very little. It was better to spare yourself and the people around you the charade. The fact was, you couldn’t make anybody happy, truly happy – not your parents, not your partner, not your kids nor colleagues, nor posterity – unless you were happy and fulfilled yourself. It was not always the simpler choice; oftentimes, it was easier to be miserable, it was easier to be a doormat than to stand up for your inviolable right to happiness. But it was a choice you made.

I am not a victim

So far, I’ve led a pretty privileged life. I’ve never known hunger, or homelessness, or direct violence or abuse, none of the unimaginable hardships that form reality for millions of people around the world. All of us, sitting at our laptops or scrolling down our smart phones, are familiar with the ordinary struggles of human existence – death and sickness in the family, relationship troubles, financial crises – but nothing as shattering as the experience of a child in a war-torn country, a family who has lost everything in a natural disaster, the victim of racism or religious persecution, a refugee, an addict, a prisoner, a slave.

Given the enormous advantages that we already have, there is really no excuse for us to feel sorry for ourselves, or vainly blame others for our own unhappiness. We are not victims, and we are certainly not helpless. We are lucky enough to be able to choose what we want to do, how we want to live. We are lucky enough to be able to make our own decisions, chart our own priorities, control the course of our lives with some degree of certainty (putting aside a percentage for qismat, of course). It could be, for example, choosing to spend on a holiday rather than a new piece of jewelry, or exercising instead of watching TV. Or it could be something more far-reaching, like deciding to move to a new country, taking on a new job, having a baby.

The bottom line is, we all are blessed. We all have gifts, we all have dreams, and most importantly, we all have volition. We just need to muster up the courage to pull those tricks out from our magic bags and put them to use, in spite ourselves.

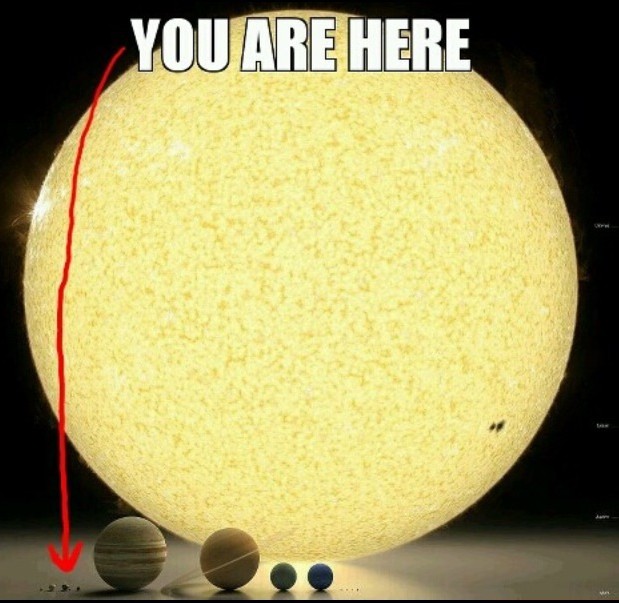

I am rather insignificant

So, what have I learnt about life after 30 years? It doesn’t seem like a whole lot, even by earthly accounts. In the universal scheme of things, it’s embarrassingly negligible…

But, keeping things relative, as of now I feel that life is really about living. It’s not about achieving lofty goals, building lofty monuments, racking up positions, bank accounts, cars and TVs and diamonds. It’s not about pleasing others, being a hero, a saint or a superstar, devoting your life to any one cause.

It’s about finding contentment, finding beauty, finding peace in the little things. The day-to-day achievements, the seemingly mundane. You learnt a new word today. You tried a new dish. You finished an assignment before deadline. You took your kids to the movies. You caught up with an old friend. You explored a new neighborhood. You danced under the trees.

Your expectations of yourself need not be grander. Yes, you may wish to write a book one day, or set up a charity school – I know I do! I haven’t forgotten those dreams. But I’m no longer in a rush to accomplish them, nor am I going to let them dictate or frustrate my present.

I look…different!

There was a time when I’d walk out of the house with a squeaky clean face and just a dash of kajal in the eyes, ready to go to college, a dinner or a wedding; now, I use makeup on a regular basis. I even wear lipstick, something I found utterly loathsome at 20! The salon girl makes it a point to count out the growing number of white hairs on my head every time I go for a trim, shaking her head disapprovingly, “But why don’t you dye???” I find myself flipping magazines at various doctors’ clinics much more often, thanks to an array of itinerant physical pains. I’ve become more attentive to what I eat, trying my best to choose a salad or a piece of fruit over a cupcake or a toast slathered with butter and marmalade; before, I couldn’t be bothered about the lumps of sodium in ChinChin Chinaman’s hot and sour soup, or the pools of grease in the LUMS cafeteria chicken karhai.

Then there are the inner changes, the ones you can’t really see; I feel happy, but in a calmer way. I’m not in a hurry to go anywhere, do anything, be anyone. I don’t care as much of what people think of me, and I’m a lot less concerned about offending somebody over a nicety. The smudges of shyness and self-consciousness that I had retained from teenage into my 20s have all but dissipated – and life is so much easier without them! I avoid comparing myself with others, I try not to be overly self-critical (a family trait), and most of all, I remind myself to be grateful, and not take life too seriously.

And what of the idealistic goals of that fictional 10-year old CV? Well, I didn’t fall off the mark entirely when I made those predictions. So I’m not a correspondent with Al Jazeera TV, but I did work at Democracy Now, the most excellent independent TV news program in the U.S. (in my opinion!). I’m not a certified yoga instructor, but I am an uncertified Bollywood dance teacher! There’s no collection of short stories (let alone award-winning), but there is an in-progress research project and an intermittent blog. I’m not the director of any charity, but I basically do volunteer work for a living, from museums to bookstores to archaeology pits. I’d say I’ve got 2 languages down in the farr farr category, with a 3rd one in the works; and, instead of summiting the base camp of an 8,000 meter peak, I chose to throw myself out of a perfectly good airplane 1,000 meters in the sky (you do some ridiculous things in your 20s). So, all in all, I’m pretty satisfied with the 30-year report card!

As should you be with yours! There’s no need to feel despondent and have regrets about what you could have done and didn’t do; and there’s no need to panic that your “best years” are flying by so you better make “the most” of them. With good health and a little bit of qismat, every year, every day can be your best, if decide to make it so.

Thoughts on Leaving Pakistan

Published in the The Friday Times Blog, October 10th 2013

The last time I put thoughts to paper was a year and a half ago, when Z and I moved back to Pakistan from the U.S. It happened very suddenly, under very sad circumstances, and there we were – thrust into a disorienting new life, filling roles we had never anticipated, never wanted, inhabiting, once again, the cloistered, uninspiring world of Lahore’s privileged class.

Much elapsed during the past 18 months in Lahore – much to rejoice and remember. Engagements, bridal showers, weddings. Baby showers, and babies! Farewell parties and welcome-back parties, birthday parties and Pictionary parties.

PTI fever, elections, and Pakistan’s first peaceful political transition. Cliff-diving in Khanpur under a shower of shooting stars, dancing arm-and-arm with Kalash women as spring blossomed in the Hindukush, tracking brown bears and chasing golden marmots in the unearthly plains of Deosai.

I rediscovered my love of history, of abandoned old places that teemed with a thousand stories and ghosts and memories, thanks to a research job at LUMS. I spent many days wandering the cool corridors of Lahore Museum, many hours contemplating the uncanny beauty of the Fasting Siddhartha, whom I had the privilege of photographing up-close. I stood beneath the most prodigious tree in the world in Harappa. I got down on my knees with a shovel and brush during a student archaeological excavation in Taxila, personally recovering the 2, 000-year old terracotta bowl of a Gandhara Buddhist monk.

But, there was also dissatisfaction. Frustration. Restlessness. When we were not travelling, we were in Lahore. And Lahore was, well, warm. Convenient. Static. Living there again was like a replay of our childhood; like watching a favourite old movie on repeat. After a while it got monotonous, somewhat annoying, and a little disappointing.

In Lahore, I could see what the trajectory of my life would be, the next 10 years down. It was all planned out, neatly copied from upper-class society’s handbook, with but minor divergences here and there.

It wasn’t a bad plan. In fact, it was a perfectly good, even cushy plan, one that would have made a lot of people quite happy.

Not me.

There were other things, too, about Lahore, and about Pakistan, things that had bothered me growing up but now seemed magnified to alarming proportions – the incomprehensible extremes of wealth and want, the insurmountable divisiveness of class, and, most worrying of all, the overwhelming self-righteousness and religiosity.

You could not escape it. Everywhere, from TV talk shows to political rallies, drawing rooms to doctors’ clinics, there was a national fixation with religion. Everybody, it seemed, was desperate to convince others – and themselves – of their absolute piety, their A+ scorecard-of-duties-towards-God, their superficial Muslim-ness. Instead of the genuine, unselfconscious goodness that shines through truly spiritual people, in Pakistanis I just saw fear. Religion for them wasn’t about peace, and love, and knowledge. Religion was base. Religion was social security. Religion was a tool of power.

I wanted to say to these superficial Muslims, to all Pakistanis: Just look at the state of our country. Do you really believe that religion has helped us? Has it at any level, be it individual, societal or state, improved the country? Has it alleviated poverty, reduced rape and murder, mitigated corruption?

Have we as a nation achieved anything positive, anything progressive, in the suffocating garb of “religion”?

No. On the contrary, we, as a nation, have become more intolerant, more oppressive, more barbaric, as our outward religious zeal reaches new heights.

And we still do not realize it. The Matric-fail maulvi at the local mosque still preaches that a woman wearing jeans in public is jahannumi, Hell-bound , the TV reporter interviewing an old peasant who has lost his home in a flood wants to know if he kept his Ramzaan fasts, and that educated, apparently “modern” aunty you met at a family dinner launches into a sermon that the reason Pakistan is beset with crises is because we don’t pray enough.

That was the most terrifying thing I found about Lahore, and about Pakistan. It had become a place where no other framework for discussion about the future of the country, about anything at all, was possible. We were mired in religion. We were stuck. We were deeply and hopelessly stuck.

As for the people who thought differently, the elite and “enlightened” class that I belonged to, they responded to the onslaught by retreating further and further into their elite Matrix – a sequestered, protected world where they met up with friends over Mocha Cappuccinos at trendy New York-style cafes, where they shopped for designer Italian handbags in centrally air-conditioned shopping malls, where their children spoke English with American accents and dressed up for Halloween, where alcohol flowed at raucous dance parties behind the gates of a sprawling farmhouse.

It was a parallel universe, where we all lived free, modern lives, like citizens of a free, modern country, utterly disconnected from the “other” Pakistan, the bigger Pakistan, and for all intents and purposes, the “real” Pakistan. Yet perhaps it was our only survival, the only way to keep sane and creative and happy for those of us who chose to live in our native country.

But I could not reconcile myself with it. I found it schizophrenic. Perhaps living abroad had changed me too much. I could not find balance, I could not find peace in Lahore.

So when Z applied to and got selected for a European Union PhD scholarship based in Madrid, Spain, I was thrilled – and a little relieved. Was I looking for an escape? Maybe. Was that the only solution? I don’t know.

When we left Lahore, on that eerie twilight flight in August, our lives packed into just one suitcase and backpack each, it was bittersweet. I was sad to say goodbye to loved ones, to friends and family whom I had spent such wonderful moments with in the past year and a half. I would miss being a part of their lives. And I would miss the incomparable natural beauty of Pakistan – beauty and heritage that is disappearing day by day due to neglect and ignorance.

Yet, I knew that I had to go. I knew that staying in Lahore – “settling for” Lahore – buying joras from Khaadi, attending tea parties, managing servants, the odd freelancing or part-time job at LUMS, was not going to make me happy. And we could not depend on the love of family and friends to sustain us forever. At the end of the day, everybody had their own lives to lead, their own paths to carve, their own hearts to follow.

And that is how we ended up in Madrid.

Sitting here in our apartment, a cozy, parquet-floored 1-bedroom affair, I can hear the babble of excited young voices below the window, a medley of idioms and accents; the clink of glasses and clatter of dishes from neighbouring restaurants; the smoky strumming of a flamenco guitar, the wheezy chorus of an accordion; the cries of Nigerian hawkers and Bengali street-peddlers, and the low hum of the occasional taxi cab, rolling along the cobbled streets of this lively old pedestrian barrio of the Spanish capital.

A new city, new adventures, new memories.

Thoughts on Moving Back to Pakistan

Published in the Express Tribune Blog, May 21st 2012

When my husband and I moved to the U.S., we knew that it wasn’t for good. Contrary to everybody’s assumptions, we knew that we were going to return to Pakistan, at some point in the meandering, distant future.

But we never imagined that it would be now, so suddenly, so unexpectedly, and under such sad circumstances.

As I sit here in the study of my in-laws house in Lahore this sunny April afternoon, looking out on a sumptuous garden decked with purple petunias, crimson lilies, snow-white roses and bright bougainvillea, listening to the chipper of birds and the low chatter of servants in the kitchen, New York seems like another planet – another time, another dimension, a past life that may or may not have even happened.

So many times we discussed this, our move back to Pakistan, my husband and I. Living in America had unalterably changed us; there, in our little 1-bedroom apartment complete with leaky faucets, mousey kitchens and batty landlords, independent for the first time, we realized how unnecessarily indulgent and painfully isolated our lives in Pakistan had been. While Occupy Wall Street was raging on in New York, we used to joke with each other about being the “covert Pakistani 1%” in the enthusiastic, indignant ranks of the “American 99%”.

“But I don’t think I could go back to living like the 1% or 5% in Pakistan, the way we grew up,” I used to say. “I hate the idea of being waited on by a troop of servants when I know I’m perfectly capable of doing their chores myself. I hate the idea of living in a 2-story, 4-bedroom mansion while a whole family sleeps, eats, dresses in a single cramped ‘quarter’, dusting and sweeping a dozen rooms that nobody uses. I just could not live in such a disparate situation.”

It wasn’t just upper-class guilt and a stubborn sense of egalitarianism rearing its head. There was also something else – the beauty and indelible satisfaction of doing things yourself, of building your physical world with your own hands. Of chopping the garlic, peeling the onion, painting the wall, scrubbing the bathtub, carrying a nice heavy bag of groceries upstairs to your apartment.

Sure, I complained about it sometimes, but I was secretly proud of it too. For somebody who had never even fried an egg by herself, let alone stand in long, sweaty queues at the Post Office or trudge a mile to do laundry, the daily struggle was a revelation. It was something you shared with the people around you. You felt a camaraderie with the strangers on the subway, the families who shopped at your neighborhood grocery store, the cab drivers, the receptionists, the waiters at your favourite restaurant. No matter who they were, where they came from or what work they did, you had something more meaningful in common with them than just the colour of your passport. Call it class blindness or class ignorance, I loved the feeling.

And, naively, I believed we could replicate that sense of camaraderie and egalitarianism with the ‘common man’, in Pakistan. That we could forge an alternative, healthier, more connected way of living, different from that of our class and our our parents; we could live in a smaller house or apartment, for starters. We could learn to take public buses, and walk to the bazaar instead of taking the car or sending a servant. We were young – we didn’t need servants obsequiously lingering about all day to feed our lethargy. If we had money to spare, we could put a poor man or woman through school instead, or a training course for a skill he or she had always wanted. We could live comfortably, but simply, with less material things, less “luxuries”, fewer TVs and cars and expensive dinner sets. It was possible, I insisted. We could reinvent ourselves in Lahore too!

My husband was skeptical, realistic. “We are who we are in Pakistan – the privileged. And it’s pointless to try to be anything else, because that can’t change. We just have to do the best we can in the roles we’ve been given.”

I didn’t agree. I believed every person had the power to change their situation, even if in a very small way.

But now that we’re actually back in Pakistan, all that seems like selfish banter, a pipe dream, wholly insignificant in the larger picture. Suddenly, we find ourselves thrown into roles, situations and relationships that we never envisioned, never planned, never wanted. We find ourselves perpetuating the status quo, the class consciousness we wanted to break. I feel the Lahore lethargy seeping into my life, my mind, slowly sapping the vigour and determination I felt before. I don’t want to walk to Al Fatah anymore, people will stare. I don’t want to take the public bus, it’ll be hot and uncomfortable. I don’t want to iron my own clothes, because I’d rather sit at the computer or read a book or take a nap; besides, that’s what the maid is there for…right?

I often wish I was immune, the way people are, to the unpalatable realities we live with in Pakistan. I wish I could authoritatively give orders to the servants like they’re used to, shoo away that pesky beggar like she’s used to, tip the Al Fatah boy with a crumpled 20 rupee note because you have to give something, gloat over the few hundred rupees you “saved” from the cloth merchant because you always get a bargain – I wish I could occupy the upper-class woman’s “role” with ease and flair, but if after 22+ years of living in Pakistan I’m still not able to do it without extreme discomfort , will I ever be?

That’s not me. And I don’t want to be that person. I don’t want that “power”, that patronizing, suffocating power, and the guilt that comes with it.

Perhaps it’s impossible after all, to create that kind of life in Pakistan – the kind of life we had in America. For all its problems and its flaws, life there taught us not to take even the basics for granted. It taught us the value of hard work and instilled in us a sense of equality and humanity we had never experienced in Pakistan – a kind of class blindness. We could live in any sort of neighbourhood we chose, make friends with anyone we wanted, eat and shop where we liked, do any kind of job; and there was no judgment, no binding social norms and family legacies to contend with.

It’s true that there will always be someone who is less privileged than you. But the divide need not be so wide, so unjust, so tragic it makes you want to cry, if you only think for a moment about the difference between you and the man who cooks for you in the heat of the kitchen all day. I would rather be the 99% than the 1%, any day, in Pakistan or any other place – if only I had the choice.

Is there a Pakistan to go back to?

Published in The Express Tribune Blog, January 20th, 2011

Last week, my husband and I finally booked our return tickets to Pakistan. It was a proud moment, a happy moment, not only because we had been saving to buy them for months, but because we had not been home in nearly two years.

Two years! It seemed like a lifetime. We had missed much: babies, engagements, weddings, new additions to the family and the passing of old, new restaurants and cafés, new TV channels, even the opening of Lahore’s first Go-Karting park. I could hardly contain my excitement.

Yet, my excitement was tainted by a very strange and disquieting thought – was there even a Pakistan to go back to?

My family and friends would be there, yes, and the house I grew up in, and my high school, and the neighborhood park, and the grocery store where my mother did the monthly shopping, and our favorite ice cream spot…

But what of the country? And I’m not talking about the poverty, and corruption, and crippling natural disasters – I’m talking about a place more sinister, much more frightening…

A place where two teenage boys can be beaten to death by a mob for a crime they didn’t commit, with passersby recording videos of the horrific scene on their cell phones…

A place where a woman can be sentenced to hang for something as equivocal as “blasphemy”…

A place where a governor can be assassinated because he defended the victim of an unjust law, and his killer hailed as a “hero” by religious extremists and educated lawyers alike…

This is not the Pakistan I know. This is not the Pakistan I grew up loving. This bigoted, bloodthirsty country is just as alien to me as it is to you.

The Pakistan I know was warm, bustling and infectious, like a big hug, a loud laugh – like chutney, bright and pungent, or sweet and tangy, like Anwar Ratol mangoes. It was generous. It was kind. It was the sort of place where a stranger would offer you his bed and himself sleep on the floor if you were a guest at his house; a place where every man, woman or child was assured a spot to rest and a plate of food at the local Sufi shrine. A place where leftovers were never tossed in the garbage, always given away, where tea flowed liked water and where a poor man could be a shoe-shiner one day, a balloon-seller the second, and a windshield-wiper the third, but there was always some work to do, some spontaneous job to be had, and so, he got by.

My Pakistan was a variegated puzzle – it was a middle-aged shopkeeper in shalwar kameez riding to work on his bicycle, a 10-year old boy selling roses at the curbside, a high-heeled woman with a transparent pink dupatta over her head tip-tapping to college, with a lanky, slick-haired, lovelorn teenager trailing behind her.

A Michael Jackson-lookalike doing pelvic thrusts at the traffic signals for five rupees, a drag queen chasing a group of truant schoolboys in khaki pants and white button-down shirts. Dimpled women with bangled arms and bulging handbags haggling with cloth vendors, jean-clad girls smoking sheesha at a sidewalk café, and serene old men in white prayer caps emerging from the neighborhood mosque, falling in step with the endless crowd as the minarets gleamed above with the last rays of the sun in the dusty orange Lahore sky.

My parents were practicing Muslims, and religion was always an important part of my life. Like most Pakistani children, my sister and I learnt our obligatory Arabic prayers at the age of 7; I kept my first Ramadan fast when I was 10, bolting out of bed before dawn for a sublime sehri of parathas, spicy omelettes, and jalebi soaked in milk. By the time I was 13, I had read the Holy Qur’an twice over in Arabic, with Marmduke Pickthall’s beautifully gilded English translation.

But beyond that – beyond and before the ritual, or maddhab, as they say in Sufism, came the deen, the heart, the spirit of religion, which my parents instilled in us almost vehemently, and which to me was the true message of Islam – compassion, honesty, dignity and respect for our fellow human beings, and for every living creature on the planet.

So, while we as Pakistanis had our differences, and practiced our faith with varying tenor – some were more “conservative” than others, some more “liberal”, some women did hijab while others didn’t, some never touched alcohol while others were “social drinkers” – we were all Muslim, and nobody had the right or authority to judge the other, no red-bearded cleric or ranting mullah. There were no Taliban or mullahs back then; if they existed, we never saw them. Not on TV, not in the newspapers, not on the streets, in posters or banners or fearsome processions.

It wasn’t a perfect society – far from it. Inequality and abuses were rampant, and daily life for a poor person could be unbearable. But they were the kind of problems that every young, developing, post-colonial nation faced, and the worst thing that could happen to you when you stepped out of the house was a petty mugging or a road accident, not a suicide blast. It was chaotic, but it was sane.

Then 9/11 happened, and society as my generation knew it began to unravel.

It started as a reaction to the U.S.-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and the “clandestine” war in Pakistan – a reaction shared by Pakistanis across the social spectrum. But somewhere along the way, the anger and grief mutated into a suicidal monster of hatred, robed in religion and rooted in General Zia’s pseudo-Islamic dictatorship of the 1980’s and the U.S.-funded Afghan jihad. Pakistan was engulfed by a frenzy, an unspeakable frustration, not only at the neighboring war that had expanded into its heartland, but at everything that was wrong with the country itself. And, like the hysteria that fueled the Crusades or the 17th-cenutry Salem witch-hunt, religion was the most convenient metaphor.

I don’t claim to understand it all, or be able to explain it. But what I do know is that, alongside the two purported targets of the “War on Terror”, there is no greater victim of 9/11 than America’s indispensable, ever-“loyal” ally and doormat, Pakistan itself.

Maybe I’m romanticizing a little. Maybe I’m being over-nostalgic about the past, and the Pakistan of my childhood. But that’s the only way I can retain some affection for my country, the only way I can sustain the desire to go back and live there – if I know and remember in my heart, that it has been better. That it was not always like this. That it was once rich, multifaceted, beautiful, tolerant, sane – and can be again.