wisdom

On heritage

“The ground on which we stand is sacred ground. It is the dust and blood of our ancestors.” – Chief Plenty Coups, Crow

Whenever I visit a new city, the first thing I like to do is pay my respects to her oldest monument.

Like the towering 12th century St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. The ancient, sprawling Palatine Hill in Rome. A ruined Moorish lookout tower in the village of Zahara de la Sierra in Andalusia. The 1000-year old dragon tree on the island of Tenerife.

Or, when I’m back in my hometown Lahore, the 10th century shrine of Ali Hajveri, the city’s patron saint and one of South Asia’s most celebrated sufis.

It’s kind of like how you make it a point to greet elders first at a family gathering, or how you always pop in to say salaam to Aunty Uncle or Daadi Daada when calling at a friend’s.

Why is it considered proper to do this?

Because age, when tempered by experience and good sense, is wisdom. And wisdom commands respect.

Our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents are the pillars of our community, our connection with the past. And much of who we are – our tastes, our temperament, the intonation of our voice, that dimple on the chin – we owe directly to them.

So it is with cultural heritage.

It’s an intangible thing, our relationship with heritage; a deep, spiritual connection that can’t be quantified, only experienced.

Like the feeling of awe you get when entering a breathtaking mosque or cathedral, in all its glazed tiled, stained glass, soaring glory. The wonder of walking through a mind-blowingly modern city like 1st century Pompeii. The peace of contemplating the Fasting Buddha at the Lahore Museum.

Or the tingling horror of seeing before you the torture instruments used during the Spanish Inquisition.

Heritage speaks to us. It moves us, because it’s an intrinsic part of ourselves. It tells us who we are, where we come from and what we’ve done – for better or for worse. Heritage gives us identity.

So when human beings destroy cultural heritage – whether purposefully, as invaders and extremists have done throughout the ages, or out of sheer stupidity and greed, as often happens in Pakistan – they aren’t just blowing up bricks and stones, or splashing white paint on a delicately frescoed tomb.

They’re erasing the identity of a society. By blotting out pieces of the past, they leave us a fragmented, rootless future. They leave us without a story.

Years and years ago, there used to exist a temple here. A sculpture. A library. A place of beauty, intelligence and culture.

But you will never know it. You will never wander its ruined pathways, finger its mossy stones, or feel that inexplicable sense of belonging, the warm pride of knowing, “My ancestors built this. And I am a part of this mysterious, timeless story.”

What will you build on now? Where will you find inspiration? How will you write the next chapter of the story?

I often feel a strong sense of déjà vu when visiting old places. There is power there, the coming together of a thousand wills, of history being constructed, brick by brick and thought by thought. Being in these places, you begin to see things differently; you begin to understand why people look the way they do, why they speak in a certain way, why they create certain things – why they are who they are, for better and for worse.

It’s like seeing old photographs of your grandparents and great-grandparents and starting at the resemblance: “That looks just like me!”

You may not like what you see, but you can’t ignore it’s there.

Cultural heritage is part of our DNA. We have a right to claim it, to cherish it, and interpret it the way we choose.

And we have a duty to preserve it, so our children and their children may also have a sacred place to call their own.

So they may also draw on that ancient repository of stones and memories, be reminded of where their ancestors went wrong – and where they went beautifully right.

So they may continue writing the story.

Farewell, fond 20s! I’m ready to move on

Why do we expect so much of life, and of ourselves? Why do we choose to be unhappy? Some questions pondered, some lessons learnt, some wisdom received

Published in Dawn Blogs, May 26th 2015

Once, when I was an undergraduate at LUMS in Pakistan, we were asked to create “future” CVs for ourselves, imagining where we would be 10 years down the road. According to my calculations, by age 30 I would be an acclaimed international affairs correspondent with Al Jazeera TV. I would also be a certified yoga instructor, the author of an award-winning collection of short stories, and the co-director of a charity school in Pakistan. I would have trekked to the base camp of an 8,000-meter peak (if not summited the peak itself), and I’d be speaking 5 languages like a native, or as we say in Urdu, farr farr.

A few weeks ago, I celebrated my 30th birthday. And looking back at that smug, overambitious piece of paper (I still have a copy), what do you suppose I felt? Disappointment, at falling short on pretty much all of my grandiose goals? Guilt, for being lazy, for not doing “enough”, for not “living up to my potential”? Anger, at myself, at people around me, at the circumstances that thwarted my legendary ascent to that 8,000-meter peak and to age 30?

No. I only laughed! Frankly, I couldn’t give a baboon’s butt about goals, objectives, achievements that you could enumerate on a CV, that you could neatly check off from a “bucket list” and be done with. I didn’t care about what I may have expected from life 10 years ago, 5 years ago, even 1 year ago.

I used to care, I used to care a lot. During my 20s, I was beleaguered by that pervasive pressure to “achieve”, all too familiar to us Millennials. Often times, we weren’t even sure of what we wanted to achieve; it could be an important position at a multinational corporation or a big bank, it could be starting our own business, running an NGO, getting a PhD, “making a difference”. Yes, what we wanted most of all was to make a difference, to “change the world”.

I am not a superhero!

I stopped thinking like that some time ago, and it was a conscious decision. I stopped thinking that I could change the world.

That’s not to say that I became cynical. I just realized that I, as one individual, did not have the power to change or “save” the world. I couldn’t eradicate poverty. I couldn’t stop wars. I couldn’t ensure that every child on the street went to school, that no woman was raped by any man. I couldn’t put an end to meaningless violence, I couldn’t reverse global warming.

I couldn’t carry through any of this in my own hometown Lahore, let alone the entire world. The world was chockfull of problems, had always been, and would always be. It was the sorry fate of humankind. And to think that you were somehow “special”, that you could clean up a mess that was centuries, millenia in the making just like you’d solve a nifty Math problem, was downright arrogant.

I couldn’t carry through any of this in my own hometown Lahore, let alone the entire world. The world was chockfull of problems, had always been, and would always be. It was the sorry fate of humankind. And to think that you were somehow “special”, that you could clean up a mess that was centuries, millenia in the making just like you’d solve a nifty Math problem, was downright arrogant.

Once in a while, perhaps once in every generation, somebody exceptional came along. Extraordinary people who, by dint of birth, effort, circumstance, and some serendipitous conjunction of the stars, did extraordinary things. The world’s heroes and heroines, revolutionaries and prophets, thinkers and humanitarians, inventors and scientists, artists and writers, whose names we all read in history books. I don’t suppose that any of these great people ever planned on changing the world, or becoming famous. I don’t suppose they wrote about it in their college applications, or scribbled it on their “bucket lists”.

I think they were just going about their lives, one day at a time, doing whatever it was they loved and believed in – not expecting any accolades or honors, not preoccupying themselves too much with “results”, just following their intuition, being themselves.

That’s one thing we all have the power to do; be ourselves. Improve ourselves, and consequently, have a positive effect on everything around us.

It could be something as simple as, say, recycling your trash. Giving a sandwich to the homeless man on your street. Holding open the door for an old lady at the metro station. Lending an ear to a friend who’s had a bad day. Giving somebody an unexpected gift. Teaching somebody a skill, or learning something new yourself. Making friends with somebody from a different religion, ethnicity, culture and country. Making the world a more tolerant, a more peaceful, kinder and happier place by embodying those qualities in your own person.

That was, realistically, the best I could do, and it was enough for me. There was no point in beating yourself up over “failed” ambitions or irrational expectations, neither your own nor those of others.

I am not a martyr or a saint!

The expectations of others, or “What will people think!”. We’ve all been oppressed by them – from something as trivial as buying the “right” gift for a birthday party, “having” to attend a cousin’s friend’s brother’s wedding or wearing the “right” outfit to a family lunch, to being emotionally coerced into a marriage by your parents, putting up with an abusive husband, sticking with a job that daily sucks the life out of you. Why? Because that’s what you’re expected to do. That’s what a good, responsible, respectable man or woman does. A good, responsible, respectable person makes everybody happy – everybody except himself. A good person is a martyr.

Now, there may be people out there who would gladly suffer all these societal tortures, and many more, out of a genuine sense of duty, or out of pure selflessness. But most of us are not like that. We are not selfless. We are not saints. We may like to think we are, but deep down inside, where nobody can hear our true thoughts, we ask ourselves: “Why am I doing this? Is it worth it? I’m fulfilling all my ‘duties’, but why am I still so miserable?”

There’s something perversely romantic about misery, the notion of sacrificing your life for the sake of others, for your children, parents, friends, your community and country, without a thought to your own wishes and desires. Whether or not you enjoy being cast in that role, society will definitely love you for it.

On the other hand, society will not take kindly to seeing you happy. That’s just shameless. And, if you insist on being so brazenly optimistic, then at least pretend to have something to gripe about!

This kind of thinking is typical among desis (South Asians), and I was done with it. If your actions didn’t spring from love or genuine kindness, if your only motivation was to “live up to” some vague ideal or ill-conceived expectation, the fear of what people might say, then those actions were worth very little. It was better to spare yourself and the people around you the charade. The fact was, you couldn’t make anybody happy, truly happy – not your parents, not your partner, not your kids nor colleagues, nor posterity – unless you were happy and fulfilled yourself. It was not always the simpler choice; oftentimes, it was easier to be miserable, it was easier to be a doormat than to stand up for your inviolable right to happiness. But it was a choice you made.

I am not a victim

So far, I’ve led a pretty privileged life. I’ve never known hunger, or homelessness, or direct violence or abuse, none of the unimaginable hardships that form reality for millions of people around the world. All of us, sitting at our laptops or scrolling down our smart phones, are familiar with the ordinary struggles of human existence – death and sickness in the family, relationship troubles, financial crises – but nothing as shattering as the experience of a child in a war-torn country, a family who has lost everything in a natural disaster, the victim of racism or religious persecution, a refugee, an addict, a prisoner, a slave.

Given the enormous advantages that we already have, there is really no excuse for us to feel sorry for ourselves, or vainly blame others for our own unhappiness. We are not victims, and we are certainly not helpless. We are lucky enough to be able to choose what we want to do, how we want to live. We are lucky enough to be able to make our own decisions, chart our own priorities, control the course of our lives with some degree of certainty (putting aside a percentage for qismat, of course). It could be, for example, choosing to spend on a holiday rather than a new piece of jewelry, or exercising instead of watching TV. Or it could be something more far-reaching, like deciding to move to a new country, taking on a new job, having a baby.

The bottom line is, we all are blessed. We all have gifts, we all have dreams, and most importantly, we all have volition. We just need to muster up the courage to pull those tricks out from our magic bags and put them to use, in spite ourselves.

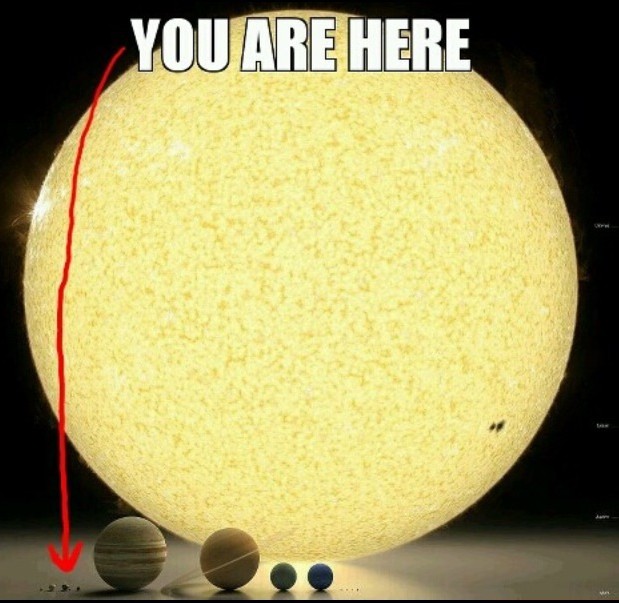

I am rather insignificant

So, what have I learnt about life after 30 years? It doesn’t seem like a whole lot, even by earthly accounts. In the universal scheme of things, it’s embarrassingly negligible…

But, keeping things relative, as of now I feel that life is really about living. It’s not about achieving lofty goals, building lofty monuments, racking up positions, bank accounts, cars and TVs and diamonds. It’s not about pleasing others, being a hero, a saint or a superstar, devoting your life to any one cause.

It’s about finding contentment, finding beauty, finding peace in the little things. The day-to-day achievements, the seemingly mundane. You learnt a new word today. You tried a new dish. You finished an assignment before deadline. You took your kids to the movies. You caught up with an old friend. You explored a new neighborhood. You danced under the trees.

Your expectations of yourself need not be grander. Yes, you may wish to write a book one day, or set up a charity school – I know I do! I haven’t forgotten those dreams. But I’m no longer in a rush to accomplish them, nor am I going to let them dictate or frustrate my present.

I look…different!

There was a time when I’d walk out of the house with a squeaky clean face and just a dash of kajal in the eyes, ready to go to college, a dinner or a wedding; now, I use makeup on a regular basis. I even wear lipstick, something I found utterly loathsome at 20! The salon girl makes it a point to count out the growing number of white hairs on my head every time I go for a trim, shaking her head disapprovingly, “But why don’t you dye???” I find myself flipping magazines at various doctors’ clinics much more often, thanks to an array of itinerant physical pains. I’ve become more attentive to what I eat, trying my best to choose a salad or a piece of fruit over a cupcake or a toast slathered with butter and marmalade; before, I couldn’t be bothered about the lumps of sodium in ChinChin Chinaman’s hot and sour soup, or the pools of grease in the LUMS cafeteria chicken karhai.

Then there are the inner changes, the ones you can’t really see; I feel happy, but in a calmer way. I’m not in a hurry to go anywhere, do anything, be anyone. I don’t care as much of what people think of me, and I’m a lot less concerned about offending somebody over a nicety. The smudges of shyness and self-consciousness that I had retained from teenage into my 20s have all but dissipated – and life is so much easier without them! I avoid comparing myself with others, I try not to be overly self-critical (a family trait), and most of all, I remind myself to be grateful, and not take life too seriously.

And what of the idealistic goals of that fictional 10-year old CV? Well, I didn’t fall off the mark entirely when I made those predictions. So I’m not a correspondent with Al Jazeera TV, but I did work at Democracy Now, the most excellent independent TV news program in the U.S. (in my opinion!). I’m not a certified yoga instructor, but I am an uncertified Bollywood dance teacher! There’s no collection of short stories (let alone award-winning), but there is an in-progress research project and an intermittent blog. I’m not the director of any charity, but I basically do volunteer work for a living, from museums to bookstores to archaeology pits. I’d say I’ve got 2 languages down in the farr farr category, with a 3rd one in the works; and, instead of summiting the base camp of an 8,000 meter peak, I chose to throw myself out of a perfectly good airplane 1,000 meters in the sky (you do some ridiculous things in your 20s). So, all in all, I’m pretty satisfied with the 30-year report card!

As should you be with yours! There’s no need to feel despondent and have regrets about what you could have done and didn’t do; and there’s no need to panic that your “best years” are flying by so you better make “the most” of them. With good health and a little bit of qismat, every year, every day can be your best, if decide to make it so.