World

On heritage

“The ground on which we stand is sacred ground. It is the dust and blood of our ancestors.” – Chief Plenty Coups, Crow

Whenever I visit a new city, the first thing I like to do is pay my respects to her oldest monument.

Like the towering 12th century St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. The ancient, sprawling Palatine Hill in Rome. A ruined Moorish lookout tower in the village of Zahara de la Sierra in Andalusia. The 1000-year old dragon tree on the island of Tenerife.

Or, when I’m back in my hometown Lahore, the 10th century shrine of Ali Hajveri, the city’s patron saint and one of South Asia’s most celebrated sufis.

It’s kind of like how you make it a point to greet elders first at a family gathering, or how you always pop in to say salaam to Aunty Uncle or Daadi Daada when calling at a friend’s.

Why is it considered proper to do this?

Because age, when tempered by experience and good sense, is wisdom. And wisdom commands respect.

Our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents are the pillars of our community, our connection with the past. And much of who we are – our tastes, our temperament, the intonation of our voice, that dimple on the chin – we owe directly to them.

So it is with cultural heritage.

It’s an intangible thing, our relationship with heritage; a deep, spiritual connection that can’t be quantified, only experienced.

Like the feeling of awe you get when entering a breathtaking mosque or cathedral, in all its glazed tiled, stained glass, soaring glory. The wonder of walking through a mind-blowingly modern city like 1st century Pompeii. The peace of contemplating the Fasting Buddha at the Lahore Museum.

Or the tingling horror of seeing before you the torture instruments used during the Spanish Inquisition.

Heritage speaks to us. It moves us, because it’s an intrinsic part of ourselves. It tells us who we are, where we come from and what we’ve done – for better or for worse. Heritage gives us identity.

So when human beings destroy cultural heritage – whether purposefully, as invaders and extremists have done throughout the ages, or out of sheer stupidity and greed, as often happens in Pakistan – they aren’t just blowing up bricks and stones, or splashing white paint on a delicately frescoed tomb.

They’re erasing the identity of a society. By blotting out pieces of the past, they leave us a fragmented, rootless future. They leave us without a story.

Years and years ago, there used to exist a temple here. A sculpture. A library. A place of beauty, intelligence and culture.

But you will never know it. You will never wander its ruined pathways, finger its mossy stones, or feel that inexplicable sense of belonging, the warm pride of knowing, “My ancestors built this. And I am a part of this mysterious, timeless story.”

What will you build on now? Where will you find inspiration? How will you write the next chapter of the story?

I often feel a strong sense of déjà vu when visiting old places. There is power there, the coming together of a thousand wills, of history being constructed, brick by brick and thought by thought. Being in these places, you begin to see things differently; you begin to understand why people look the way they do, why they speak in a certain way, why they create certain things – why they are who they are, for better and for worse.

It’s like seeing old photographs of your grandparents and great-grandparents and starting at the resemblance: “That looks just like me!”

You may not like what you see, but you can’t ignore it’s there.

Cultural heritage is part of our DNA. We have a right to claim it, to cherish it, and interpret it the way we choose.

And we have a duty to preserve it, so our children and their children may also have a sacred place to call their own.

So they may also draw on that ancient repository of stones and memories, be reminded of where their ancestors went wrong – and where they went beautifully right.

So they may continue writing the story.

The Legend of Saif-ul-Malook Part VI

Lake Saif-ul-Malook, situated at a height 10, 600 feet at the northern tip of the Kaghan Valley in Pakistan’s Himalayas, is one of the most beautiful places on earth. I have been there twice, the first time as a 12-year old and then in 2009, when I determined to capture some of its magic on camera and on paper, in the words of two local storytellers who relate the legend of the Lake to visitors.

It is the story of a prince and a fairy, Saif-ul-Malook and Badr-ul-Jamal – a story of love, adventure, faith, magic, suffering and betrayal – a story of the multitude of human passions.

Many different versions exist, but below is a reproduction of what the storytellers told us, with ample writer’s liberties. I hope you enjoy it!

Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV & Part V of the story

Now, you may wonder, what was Prince Saif up to at the moment Badr Jamal made her escape from the Palace in the shape of a white dove?

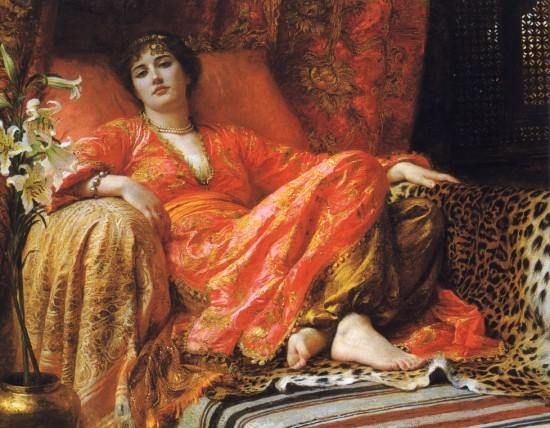

In fact, he was resting beneath the shade of an ebony tree deep in the woodlands of Nubia, after a fruitful but exhausting deer hunt. Eyes half-closed, stretched out on the soft green grass, he was thinking sweet thoughts about his beloved Fairy Queen, when a little white dove came and alighted on a branch above him.

It seemed to Saif that she was the prettiest dove he had ever seen – even though he didn’t consider himself a “bird person” – and he was suddenly possessed by a desire to capture her. “She’d make a nice little pet for my beautiful Badr,” he mused. So, he quietly got to his feet, picked up a net that lay amongst his hunting paraphernalia, and flung it over the bird.

But the net, as if repelled by an invisible force, bounced straight back at him, while the dove sat merrily on her perch untouched. Saif tried a second time to ensnare the bird, then a third, with the same perplexing result.

Then – and Saif could hardly believe his eyes or his ears, though he had witnessed his fair share of fantastic events – the dove turned her soft white head towards the Prince and spoke to him, in voice he could recognize among millions:

“Your attempts to capture me are in vain, Prince Saif. You can never own me. You can never possess me.”

It was Badr Jamal, of course.

“The only way to convince me of your love,” the bird continued, “the only way you will truly earn my love, is if you follow me to Paristan, my homeland. If you succeed in this, if you are able to brave the journey and seek me out in my father’s palace, among my own kind, I promise I will come back with you, as your wife and partner in life. And I will never leave your side till as long as you live.”

With these words, Badr Jamal fluttered her snowy white wings and was off, leaving Saif in a state of utter discombobulation.

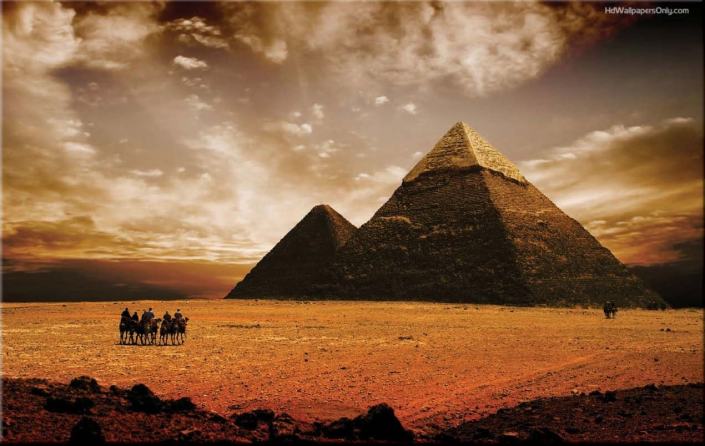

On his return to Egypt, one look at his mother’s swollen red eyes and the funereal aspect of the Palace confirmed Saif’s worst suspicions – Badr Jamal, his beloved, the person he cherished more than anything else in the world, the person whom he had struggled to attain for six long, arduous years, was gone.

Saif didn’t want to hear anything. What had happened during his brief absence from the Palace? Why? How? All that was irrelevant now. He knew what he had to do.

“Mother, please tell one of the servants to saddle up a good, strong horse and prepare me a travel bag, with enough provisions to last about a month. I’m leaving right away.”

“But, Saif!” his mother pleaded. “Don’t you see? Badr Jamal doesn’t want to be here! Let her go, Saif. She is happier with her own kind. Please, just forget about her! There is no dearth of beautiful ladies here in Egypt. Think, Saif, destiny has afforded you a second chance at a happy, normal life. Don’t gamble it away for an illusion, for a fantasy, my son! Don’t let this madness get the better of you!”

However, as before, the Queen Mother’s weeping, wailing and emotional threats had no effect on Prince Saif’s resolve. He was an obstinate fellow, and he truly did love Badr. Just as he had found his way to the magical lake in Kaghan Valley, just as he had completed the 40-day penance, the chilla, and escaped from the Ogre and the Flood with Badr in his arms, so he would bring her back from the deepest, darkest dungeons of Paristan if he had to.

“I’m sorry, Mother,” he embraced the Queen one final time before mounting his ride. “But I can’t give up without even trying.” Kicking the horse into a gallop, Saif rode away from the Palace a second time, without looking back.

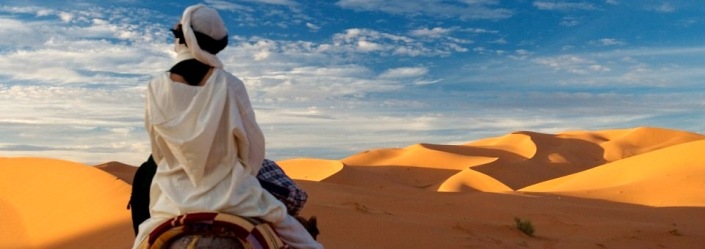

Now, Prince Saif didn’t really know where Paristan was, or whether it even existed. Legends placed the kingdom of the fairies “east of Egypt”, somewhere on the mountainous border of Persia and India – and the directions stopped there.

So, he travelled east for several months, crossing Sinai, the fabled rivers Tigris and Euphrates of Mesopotamia, the Great Salt Desert of Persia, the Snowy Mountains of Afghanistan, stopping time to time at some shepherd’s hut or sarai, a highway inn, to rest and refresh his supplies.

Many times he cursed himself for forgetting to carry his Sulemani topi, the magic cap bequeathed to him by the old buzurg during his first quest, which had the power to transport its wearer to any place on earth in the twinkling of an eye.

“I suppose I’m not allowed any shortcuts this time,” he grumbled.

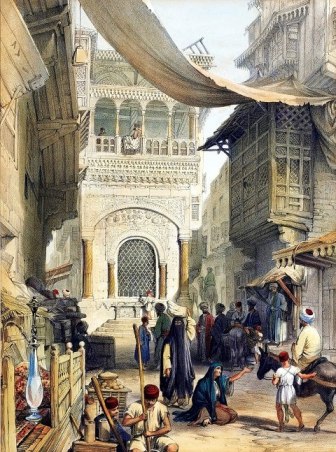

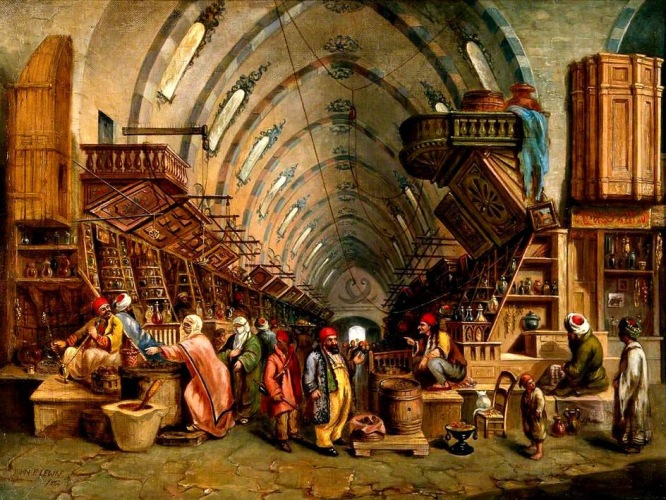

At length, Saif reached Peshawar, or Purushapura, as it was known then, the bustling western capital of the Kushan Empire, gateway to the Indian subcontinent. Merchants from all corners of the Silk Route thronged its narrow streets, hawking their varied wares in loud voices – silk, cashmere, cotton, spices, dry fruit, wine, carpets, woodwork, decorative objects of marble, ivory and jade, gemstones, weapons, secrets and stories – there was nothing you could not find in the legendary markets of Purushapura.

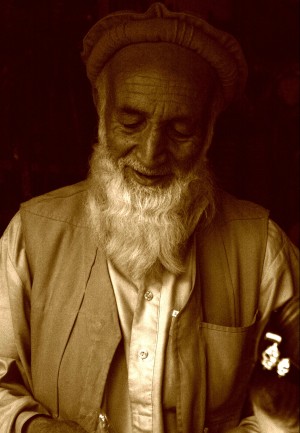

Meandering through the bazaar while his horse rested in the city’s stables, Prince Saif stopped at a chai khana, a tea shop, for a cup of the traditional Peshawari kahwa, hot green tea sweetened with honey or sugar and spiced with cardamom. Looking around the crowded little shop for a place to sit, he spotted an empty stool next to an old man with a flowing white beard, who sat calmly sipping his tea and fingering a rosary.

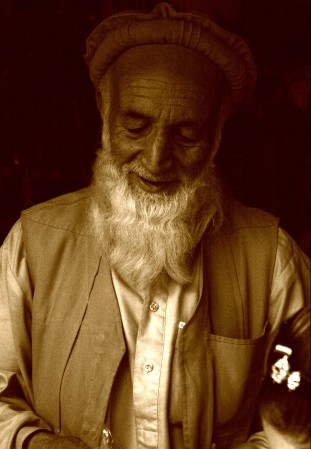

Prince Saif walked up to the old man, saluted him with a respectful bow, and said, “Venerable sir, would you be so kind as to allow this weary traveller to seat himself beside you?”

The old man looked up at Saif. Their eyes met, and Saif had the sensation that he knew him from somewhere; that this was not a chance encounter. “My son!” the old man smiled, eyes crinkling at the corners. “Please, it would be my honor.

“And now, tell me,” he continued, once Saif had made himself comfortable and given his order. “What brings a gentleman like yourself to this wily merchant’s city?”

Quickly, Prince Saif related to his new friend the objective of his journey: to reach the mythical land of Paristan (which, according to legend, lay somewhere in these parts), and recover his beloved Fairy Queen and true wife, Badr Jamal.

“Paristan? My dear lad!”, the old man let out a bemused chortle. “You know the reason why they call it a ‘mythical’ land? Because Paristan has no physical existence! You will not find it on any map, you will not see any signboards pointing out the way, no gates or city walls to saunter through. On the whole, it is entirely impossible for you to reach there in your present state.”

Seeing Prince Saif’s face fall in despair at this rude reality check, the old man hurried to add. “Oh, but don’t look so glum! The good news is that I can help you. Or, at least I have some things that could help you…” He started rummaging through the coarse jute sack he carried, and duly produced a tattered woolen cloak, and a short wooden staff. Saif was overcome by déjà vu.

“I’m sorry, sir,” he interrupted. “But I feel like we’ve met before. Were you ever in Egypt some years back?”

“Nonsense, son! I’ve never set foot outside the city of Peshawar,” the old man hastily brushed aside the question. “Now, listen to me carefully – for although I have not travelled much, I have learnt a great deal in the long journey of my life, from observing and talking to all the people that pass through this city. And what I tell you now may well be the only hope you have of penetrating Paristan and seeing your wife again…”

It was true. Once more, a nameless old buzurg was to be Prince Saif’s savior.

A few hours later, Prince Saif found himself riding with a caravan of merchants towards Tattoo, a small village in the kingdom of Gilgit, perched on the craggy slopes of the magnificent Karakoram mountains. The merchants, heading for China via the Khunjerab Pass, had agreed to drop Saif off at the village in exchange for his horse, a handsome Arabian steed that would fetch a weighty price in the horse fairs of the Mongolian steppe.

Saif parted with the animal with a heavy heart, but he actually had no further use for it. His real destination was 13 miles further off Tattoo, where no horse or mule tracks led; a place called Joot, today famous by its English appellation, Fairy Meadows.

“I have never been to Joot, but I hear tell that it is a most breathtaking place,” the old man at the tea shop had recounted. “They say that a Fairy King of great power established his kingdom there, some 1,000 years ago, in the shadow of that fearsome peak Nanga Parbat, the Naked Mountain.

“Nobody lives in Joot. The locals are wary of venturing there at all because of all the stories; shepherds who went to graze their flocks and never returned; explorers, bandits, naturalists and mystics, attracted to the place by its beauty and its solitude, and never seen again. It is enchanted, they say, the abode of witches and jinns, as perilous as it is beautiful.

“This is where you must go.”

And that is where Saif had arrived, after a grueling uphill hike from Tattoo, following the old man’s directions to the letter. He stood in the middle of a vast green meadow, facing the awesome, ice-covered Nanga Parbat. Dusk was approaching, and there was not a soul in sight. All was silent, except for the gentle hum of the evening breeze amongst the pines.

Saif pulled out from his satchel the tattered woolen cloak. “Once you don this cloak,” the old man had explained, “everything around you that is made from the hands of men, will dissolve from view. Buildings, roads, entire cities, will simply vanish.

“And everything that was hitherto unseen – the realm of jinns and fairies, and all other manner of supernatural creatures – will suddenly come to light, as real, as tangible, as indubitable as that tea cup you hold in your hands.”

As for the wooden staff, the old man had said he had bought it from a wandering Jewish mendicant, who claimed that the staff contained a tiny fragment of the miraculous staff of Moses. Placed in the right hands, it had the power to unlock or open any kind of barrier – gates, doors, chains – both magical and mundane.

Standing before that gigantic mountain in the grassy fields of Joot, the very location of Paristan, all that was left for Saif to do was throw on the cloak, brandish the staff, and smash his way into the Fairy King’s palace to recover his bride.

But Saif hesitated. What if all of this was a lie? What if the old man had tricked him? And now, there he was, alone in that desolate spot with no food, no shelter, no money, not even his horse to help him retrace his steps and make the long journey home…

By this time it was almost completely dark, and a silver slipper of a moon had begun to glimmer above the jagged peaks of the Karakoram.

“Well, I don’t really have another plan, so I might as well give this a shot,” Saif thought. So, taking a deep breath, he grasped the wooden staff and wrapped the woolen cloak tightly around him….

The things that happened henceforth are better left imagined. For sometimes there are sights so wondrous, events so singular that they defy description.

Let’s just say that the old man in the tea shop had known what he was talking about!

Read Part VII, the final instalment of the story

Madrid Diaries: Unemployed but Happy

“I’ve learned that making a ‘living’ is not the same thing as making a ‘life.’” ~ Maya Angelou

Whenever I meet somebody new and they find out, during the course of the conversation, that I’ve been jobless for over one year, living in a foreign country where I have no family or prior acquaintances, and where I just barely speak the language, they look at me incredulously, stupefied: “But what do you do all day? How do you survive? Aren’t you bored to death?”

Let me just mention here that my lack of gainful employment has little to do with laziness, unwillingness, or the “handsome fortune” I may possess, and mostly to do with my legal status in Spain (residencia sin trabajo – residency without work), coupled with the language barrier (dam, rather) that I’m still slowly chipping away at.

But I find it odd, the amount of importance people attach to what you “do” for a living. I myself used to be one of those people: ever since college, I had never been without a job of some sort, full-time, part-time, internship, fellowship, what have you. Even though I wasn’t particularly ambitious or “career-driven”, I took pride in the work I did, because I saw it as a “productive” use of my time, as a contribution towards my own financial wellbeing, and as a logical step forward in my profession, another glittering addition to my resume. And, even if none of that held true, at least I would have a response to that piquing, unrelenting question, the backbone of social banter – “So, what do you do?” I could define myself in one neat, clean, impressive title, and immediately win the other person’s respect. That felt good.

So what happened when I followed my Erasmus Mundus PhD candidate-better half to Spain? What happened when the prospect of landing a job of any kind – let alone related to my career – was suddenly as bright as a Lahori home on a sticky summer’s night? (non-Lahoris/Pakistanis, look up “load shedding” on Wikipedia!)

Well, like any respectably assiduous person, I was frustrated; frustrated with my lack of “productiveness”, uncomfortable with my own free time, guilty of spending money when I wasn’t earning any, guilty of letting my Berkeley Master’s degree “go to waste”; apologetic of my “situation” in general, sighing deeply and resignedly whenever the topic came up…

But the truth is – I wasn’t unhappy. Six months down the line, I was pretty darn happy, and far, far from bored. Society tends to evaluate people based on degrees, paychecks, publications, trophies, on solid, tangible proofs of “success” and one-word descriptions of what they “do for a living”. “I’m a doctor – actor – teacher – writer – cleaner – waiter …” As if nothing exists beyond the ambit of those rectangular brackets.

But we are so, so much more than what we do. The tragic part is that most people never have the time, the opportunity or the motivation to explore themselves beyond the one-word labels, to spill out over the edges of their rectangular holes. I figured: I’m here in this fantastic European city, lucky enough to have time, opportunity and buckets of motivation – could I really complain about my “situation”?

Now, when someone asks me the invariable, the pedestrian, “So, what do you do?”, I cheerfully reply, “Well, I’m currently employed with living”, and present to them the following list:

1. Dance

Apart from taking regular classes at the Karnak School of Oriental Dance in Madrid, I started teaching Bollywood Dance earlier this year with Tara, my partner-in-crime from across the Wagah border. Our group, Mantara, recently performed at a Diwali Dance Fiesta, where our lovely alumnas did splendidly well. Throw in Indo-Pak feasts at the local (Bangladeshi) restaurants and mini-dholkis at my house, complete with mehndi (henna), chai, retro Bollywood music videos and Coke Studio Pakistan, and home doesn’t feel so far away!

2. Song

I also recently joined Voces de Ida y Vuelta, a multicultural, multlingual choir that performs at local fundraisers and charity events. Grouped with the sopranos, I’m currently working on reaching glass-shattering pitches and memorizing Cuban, Chilean, Brazilian and Gabonese songs, with many more canciones to come – including one from Pakistan!

3. Art

I don’t “make” art (unless you count photography), but Madrid is such a fantastic place to see and appreciate all kinds of art – for free! – that you can’t help soaking it up every day, as you casually stroll through an exhibition at the neighbourhood gallery or at a random cafe, at the former Post Office, the one-time slaughterhouse or tobacco factory, at Retiro Park, or in the graffitied alleys of Malasaña. Over the course of my artistic education in Madrid, I’ve decided that I don’t particularly like (or understand) Picasso, but Dali I find fascinating (though I don’t fully understand him either). I’ve also decided that if a painting looks too much like a photograph, then it isn’t a good painting. There, my two cents of artistic wisdom!

4. Archaeology

Following up on an old dream (not inspired by Indiana Jones!), I volunteered for an archaeological excavation (read: labour camp) this summer, in the small town of Pollena Trocchia in the south of Italy. Together with 20 bright-faced archaeology undergrads from the U.S., U.K., Canada and Europe (I had to represent the brown people of the world), I dug, scraped, shoveled, pick-axed, sifted, wheelbarrowed and rolled around in incalculable amounts of volcanic soil at the site of an ancient Roman Bathhouse and Villa, destroyed in 472 C.E. by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Needless to say, working as a mazdoor under the hot Neapolitan sun and living like a mazdoor (10 perpetually filthy people sharing a perpetually filthy dorm and bathroom) gave me a whole new appreciation of the academic world, of airconditioned libraries and sparkly-floored museums, not to mention of my own sparkling bedroom and bathroom. But, inspite of it being one of the most physically challenging things I have done in my life, I’m not “cured” of my archaeology illusions quite yet!

5. Food

I’ve always been fond of tinkering around in the kitchen, and every new place inspires you to add new dishes to your repertoire. So, apart from the classic spaghetti bolognese (Pakistani style), the best Thai Green Curry you’ll ever have this side of the Pacific, and my special death-by-chocolate brownies, here are some other hearty goodies you’ll get to sample at Casa Manal. (Note: These photos are not my own, but I swear, the food looks just like this!)

6. Park

If there’s one place we’ve spent more time in Madrid than any other, it’s Retiro Park. Madrid’s main park used to be a retiro, a retreat for Spanish royals until the late 19th century, when it was opened to the public. It’s big, it’s beautiful, and you can do absolutely anything you want there, from running, biking, rollerblading, boating and gyming to yoga, tai chee, frisbee, slacklining, dancing (thanks to us!), to watching magic shows, puppets and live music, seeing art exhibitions, enjoying a coffee, lemonade or sangria (whichever you prefer), to dozing quietly in a shady corner – a little piece of paradise in the heart of Madrid.

7. Language

Apart from continuing Spanish classes at C.E.E. Idiomas and regular intercambio coffee dates with my Spanish girl friends, I’ve added a new item to the daily study regimen – Spanish TV soaps. I’ve never been much of a TV buff, but there’s a certain pleasure in ensconcing yourself on a sofa with a blanket and a box of cookies and watching a dramatic story of some other place and time unfold magically infront of your eyes on an HD TV screen. And here in Madrid, I have an excuse to watch all the TV I want! From the weighty life of Spanish “Reconquista” Queen Isabel to swashbuckling adventures in the Spanish American colonies to a feudal family drama set in a Franco-era Castillian village, I’ll be speaking the Queen’s (500 year-old diction of) Spanish in no time!

8. Volunteering

I joined the WWF (World Wildlife Fund) Madrid Volunteer Network shortly after arriving in the city, but was initally too scared to go to their weekly and monthly activities (tree plantings, bird censuses, plodding around marshes and other strange things that only me and my partner-in-crime from across the border would find enjoyable). We did make it to the Earth Hour event though, inspite of the pouring rain, proving our mettle as die-hard WWF supporters and being rewarded with Panda T-shirts. I plan to join the regular field activites as soon as the weather warms up, this time with reinforced Spanish!

9. Travel & Photography

Perhaps the best part about living in Europe is the travelling – within a few hours flight from Madrid I can be in any number of different European capitals, each with a different language, different architecture, food and feel. And if you plan in advance and are a savvy deal-hunter like I’ve become, the trip won’t cost you a euro more than it would have in your shoestring student-budget days.

But there’s so much to see in Spain itself that we haven’t yet been tempted by elaborate holidays abroad. I watch with satisfaction as the souvenir magnet collection on our fridge steadily grows, as do the number of photo archives on my computer. For me, travelling is pure thrill – every time I go to a bus terminal, a train station or an airport, I feel slightly giddy, as if I were 8 years old and about to step into Disneyland. Each time I’m wandering the streets of a new city, curiosity and a camera in hand, I feel that strange sense of belonging everywhere, yet of belonging nowhere.

And each time I travel, I’m reminded about how beautiful the world is, how diverse the world is, and how similar we all are – all of us humans, busily making lives and earning livings in whatever little patch of earth we call home. In the end, no matter what we do or don’t do, happiness doesn’t come to us. It flows from within.

How to Make Friends in a New City – Tip #5

- No te preocupes! Don’t worry! Let the universe do its thing!

This is something I’ve learnt along the course of my somewhat peripatetic life the past 6 years: sometimes, people (and opportunities) fall into your lap in the most unexpected, unlooked for way; and these congenial little windfalls may be the best things that happen to you in your new home.

I remember a certain day in Ithaca, New York, where Z and I had moved right after getting married. Z was in class at Cornell, and I was busy cleaning, unpacking and ‘nesting’ in our new apartment, a ground-floor portion of a typical East Coast colonial house, when our gritty old landlord Carl ambled up to the front door, dressed in his customary red plaid shirt and classic blue jeans. “Hey there!” Carl hollered, “I wanted to introduce you to these nice folks,” he gestured towards the smiling young couple that followed him. “They’ve just moved to Ithaca from Mexico, and are thinking of renting from me as well!”

That was the first time I met Elsa & Silvano. Though we only spoke for five minutes, standing in the porch of Carl’s yellow-painted dollhouse, and thought they didn’t end up renting from him after all, they became our closest companions the 9 months we spent in Ithaca, and we still count them among our dearest friends.

So, just like that, someone may chance to cross your path, and you’ll hit it off with them like you never imagined. Maybe a friend of a friend puts you in touch with somebody they know who happens to live in the same city; and you turn out to be kindred spirits, Anne of Green Gables-style. Or maybe another like-minded soul, going through the same experiences as you, discovers you and contacts you through your blog!

I find it so interesting, how these connections are made – magically, almost – bringing complete strangers together through no deliberated effort. So, if you ever find yourself lost, alone and friendless in a new city, wondering why on God’s earth you ever transplanted yourself in the first place: don’t worry! It takes time for a plant to adjust to new soil, a new atmosphere. But once it gets over the wilting, drooping, moping period – ‘transplant shock’ in botanical terms – it thrives. In fact, if you don’t keep an eye, it may even start merrily taking over your garden, and you won’t know what to do! :)

Happy New Year from Madrid! Here are some photos we’ve taken of the city’s squares, streets and public spaces.

Read Tip #1,Tip #2, Tip #3, Tip #4, and the introductory post of this series!

How to Make Friends in a New City – Tip #2

- JOIN A RECREATIONAL CLASS

When you’re not a full-time student, nor do you have a “’real” job, nor any family in the city where you live, you end up with a lot of free time on your hands – which can be perfectly utilized by learning something you’ve always wanted, but never really got a chance to do. For instance, crocheting, or Thai kickboxing. Sushi-making, or calligraphy, ventriloquism, or, better yet, magic!

That something for me right now is Middle Eastern dancing. I carry my black coin-belt around with me wherever we go, and Google down a dance class whichever city we happen to be in. Apart from the fact that I love to do it, it’s also a good way of meeting people – perhaps even a potential friend, whom you are assured of having at least one thing in common with!

So, with all this in mind, I joined a classical Egyptian dance class in Madrid, taught by a half-Egyptian, half-Paraguayan, Spanish-born woman called Yasmina, who has been dancing professionally for 20 years.

On my first day, I arrived late. I had gotten confused when exiting the metro station, and walked in the wrong direction for a good ten minutes. “Darn it,” I thought, when I realized my (usual) mistake. “There’s no point of going to the class now. There won’t be space for me anyway!”

I was envisaging, of course, the type of dance classes I had attended in Berkeley and New York; a normally tiny square-shaped room packed to the seams with a variety of serious-faced girls in intimidating-looking leotards; the teacher (whom you could barely see) hollering instructions, bootcamp-style, over the pounding music; and me in the back row, whacking my hands into the wall every time we did snake arms, or getting trampled on by Rubber Girl next to me at every grapevine turn.

But here, when I scrambled into class, huffing and puffing, with a “Lo siento-ooo!”, I’m sorry-yyy, on my lips, I was shocked to find myself in a 60 ft x 30 ft, hardwood-floored room, glistening mirrors on not one but three sides, nicely framed posters on the cool blue walls, and Yasmina the teacher with two students – dressed in comfy track pants and T-shirts – quietly doing some stretches.

“Is the class already over?? Has everybody left??” I asked, bewildered.

No, they were just about to start! “Solo nosotras,” Yasmina smiled, flicking on the music. I couldn’t believe it! What joy! What pleasure! What a wonderful feeling to sway about freely my unusually long limbs without colliding into an animate or inanimate object at every move!

There were even times when the other two students didn’t show up, and it was just me and the teacher, whom I could pester with complaints and questions to my heart’s content (“But why can’t I do the sideways shimmy? Why? Why doesn’t it look as good as yours?”) On the downside, nobody in the class, including the teacher, spoke any English, so we had to suffice in our communication with gestures, intonation and a range of facial expressions. The other girl in the class, who was my age, seemed nice, but I could not glean much about her from my limited Spanish and her non-existent English save that she worked at a pharmacy, loved leopard print and Khaled.

On the upside, one of the first things I mastered in the Spanish language were parts parts of the body – rodilla, tobillo, talón, cadera, codo, muñeca, cuello – much to my Spanish teacher’s amazement when we came to study that chapter in class. You bet, I knew them body parts like a doctor. And, generally, I became known amongst the nice ladies at the dance school as the funny “American” girl (because I spoke English) who laughed a lot, seemed genuinely excited to be in Spain (unlike the Spaniards themselves, who were desperate to leave), and who continually invented new ways to bungle their language – which they didn’t seem to mind at all!

Read Tip #1, Tip #3, Tip #4, Tip #5, and the introductory post of this series!

Thoughts on Leaving Pakistan

Published in the The Friday Times Blog, October 10th 2013

The last time I put thoughts to paper was a year and a half ago, when Z and I moved back to Pakistan from the U.S. It happened very suddenly, under very sad circumstances, and there we were – thrust into a disorienting new life, filling roles we had never anticipated, never wanted, inhabiting, once again, the cloistered, uninspiring world of Lahore’s privileged class.

Much elapsed during the past 18 months in Lahore – much to rejoice and remember. Engagements, bridal showers, weddings. Baby showers, and babies! Farewell parties and welcome-back parties, birthday parties and Pictionary parties.

PTI fever, elections, and Pakistan’s first peaceful political transition. Cliff-diving in Khanpur under a shower of shooting stars, dancing arm-and-arm with Kalash women as spring blossomed in the Hindukush, tracking brown bears and chasing golden marmots in the unearthly plains of Deosai.

I rediscovered my love of history, of abandoned old places that teemed with a thousand stories and ghosts and memories, thanks to a research job at LUMS. I spent many days wandering the cool corridors of Lahore Museum, many hours contemplating the uncanny beauty of the Fasting Siddhartha, whom I had the privilege of photographing up-close. I stood beneath the most prodigious tree in the world in Harappa. I got down on my knees with a shovel and brush during a student archaeological excavation in Taxila, personally recovering the 2, 000-year old terracotta bowl of a Gandhara Buddhist monk.

But, there was also dissatisfaction. Frustration. Restlessness. When we were not travelling, we were in Lahore. And Lahore was, well, warm. Convenient. Static. Living there again was like a replay of our childhood; like watching a favourite old movie on repeat. After a while it got monotonous, somewhat annoying, and a little disappointing.

In Lahore, I could see what the trajectory of my life would be, the next 10 years down. It was all planned out, neatly copied from upper-class society’s handbook, with but minor divergences here and there.

It wasn’t a bad plan. In fact, it was a perfectly good, even cushy plan, one that would have made a lot of people quite happy.

Not me.

There were other things, too, about Lahore, and about Pakistan, things that had bothered me growing up but now seemed magnified to alarming proportions – the incomprehensible extremes of wealth and want, the insurmountable divisiveness of class, and, most worrying of all, the overwhelming self-righteousness and religiosity.

You could not escape it. Everywhere, from TV talk shows to political rallies, drawing rooms to doctors’ clinics, there was a national fixation with religion. Everybody, it seemed, was desperate to convince others – and themselves – of their absolute piety, their A+ scorecard-of-duties-towards-God, their superficial Muslim-ness. Instead of the genuine, unselfconscious goodness that shines through truly spiritual people, in Pakistanis I just saw fear. Religion for them wasn’t about peace, and love, and knowledge. Religion was base. Religion was social security. Religion was a tool of power.

I wanted to say to these superficial Muslims, to all Pakistanis: Just look at the state of our country. Do you really believe that religion has helped us? Has it at any level, be it individual, societal or state, improved the country? Has it alleviated poverty, reduced rape and murder, mitigated corruption?

Have we as a nation achieved anything positive, anything progressive, in the suffocating garb of “religion”?

No. On the contrary, we, as a nation, have become more intolerant, more oppressive, more barbaric, as our outward religious zeal reaches new heights.

And we still do not realize it. The Matric-fail maulvi at the local mosque still preaches that a woman wearing jeans in public is jahannumi, Hell-bound , the TV reporter interviewing an old peasant who has lost his home in a flood wants to know if he kept his Ramzaan fasts, and that educated, apparently “modern” aunty you met at a family dinner launches into a sermon that the reason Pakistan is beset with crises is because we don’t pray enough.

That was the most terrifying thing I found about Lahore, and about Pakistan. It had become a place where no other framework for discussion about the future of the country, about anything at all, was possible. We were mired in religion. We were stuck. We were deeply and hopelessly stuck.

As for the people who thought differently, the elite and “enlightened” class that I belonged to, they responded to the onslaught by retreating further and further into their elite Matrix – a sequestered, protected world where they met up with friends over Mocha Cappuccinos at trendy New York-style cafes, where they shopped for designer Italian handbags in centrally air-conditioned shopping malls, where their children spoke English with American accents and dressed up for Halloween, where alcohol flowed at raucous dance parties behind the gates of a sprawling farmhouse.

It was a parallel universe, where we all lived free, modern lives, like citizens of a free, modern country, utterly disconnected from the “other” Pakistan, the bigger Pakistan, and for all intents and purposes, the “real” Pakistan. Yet perhaps it was our only survival, the only way to keep sane and creative and happy for those of us who chose to live in our native country.

But I could not reconcile myself with it. I found it schizophrenic. Perhaps living abroad had changed me too much. I could not find balance, I could not find peace in Lahore.

So when Z applied to and got selected for a European Union PhD scholarship based in Madrid, Spain, I was thrilled – and a little relieved. Was I looking for an escape? Maybe. Was that the only solution? I don’t know.

When we left Lahore, on that eerie twilight flight in August, our lives packed into just one suitcase and backpack each, it was bittersweet. I was sad to say goodbye to loved ones, to friends and family whom I had spent such wonderful moments with in the past year and a half. I would miss being a part of their lives. And I would miss the incomparable natural beauty of Pakistan – beauty and heritage that is disappearing day by day due to neglect and ignorance.

Yet, I knew that I had to go. I knew that staying in Lahore – “settling for” Lahore – buying joras from Khaadi, attending tea parties, managing servants, the odd freelancing or part-time job at LUMS, was not going to make me happy. And we could not depend on the love of family and friends to sustain us forever. At the end of the day, everybody had their own lives to lead, their own paths to carve, their own hearts to follow.

And that is how we ended up in Madrid.

Sitting here in our apartment, a cozy, parquet-floored 1-bedroom affair, I can hear the babble of excited young voices below the window, a medley of idioms and accents; the clink of glasses and clatter of dishes from neighbouring restaurants; the smoky strumming of a flamenco guitar, the wheezy chorus of an accordion; the cries of Nigerian hawkers and Bengali street-peddlers, and the low hum of the occasional taxi cab, rolling along the cobbled streets of this lively old pedestrian barrio of the Spanish capital.

A new city, new adventures, new memories.