Adventure

The Legend of Saif-ul-Malook Part VI

Lake Saif-ul-Malook, situated at a height 10, 600 feet at the northern tip of the Kaghan Valley in Pakistan’s Himalayas, is one of the most beautiful places on earth. I have been there twice, the first time as a 12-year old and then in 2009, when I determined to capture some of its magic on camera and on paper, in the words of two local storytellers who relate the legend of the Lake to visitors.

It is the story of a prince and a fairy, Saif-ul-Malook and Badr-ul-Jamal – a story of love, adventure, faith, magic, suffering and betrayal – a story of the multitude of human passions.

Many different versions exist, but below is a reproduction of what the storytellers told us, with ample writer’s liberties. I hope you enjoy it!

Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV & Part V of the story

Now, you may wonder, what was Prince Saif up to at the moment Badr Jamal made her escape from the Palace in the shape of a white dove?

In fact, he was resting beneath the shade of an ebony tree deep in the woodlands of Nubia, after a fruitful but exhausting deer hunt. Eyes half-closed, stretched out on the soft green grass, he was thinking sweet thoughts about his beloved Fairy Queen, when a little white dove came and alighted on a branch above him.

It seemed to Saif that she was the prettiest dove he had ever seen – even though he didn’t consider himself a “bird person” – and he was suddenly possessed by a desire to capture her. “She’d make a nice little pet for my beautiful Badr,” he mused. So, he quietly got to his feet, picked up a net that lay amongst his hunting paraphernalia, and flung it over the bird.

But the net, as if repelled by an invisible force, bounced straight back at him, while the dove sat merrily on her perch untouched. Saif tried a second time to ensnare the bird, then a third, with the same perplexing result.

Then – and Saif could hardly believe his eyes or his ears, though he had witnessed his fair share of fantastic events – the dove turned her soft white head towards the Prince and spoke to him, in voice he could recognize among millions:

“Your attempts to capture me are in vain, Prince Saif. You can never own me. You can never possess me.”

It was Badr Jamal, of course.

“The only way to convince me of your love,” the bird continued, “the only way you will truly earn my love, is if you follow me to Paristan, my homeland. If you succeed in this, if you are able to brave the journey and seek me out in my father’s palace, among my own kind, I promise I will come back with you, as your wife and partner in life. And I will never leave your side till as long as you live.”

With these words, Badr Jamal fluttered her snowy white wings and was off, leaving Saif in a state of utter discombobulation.

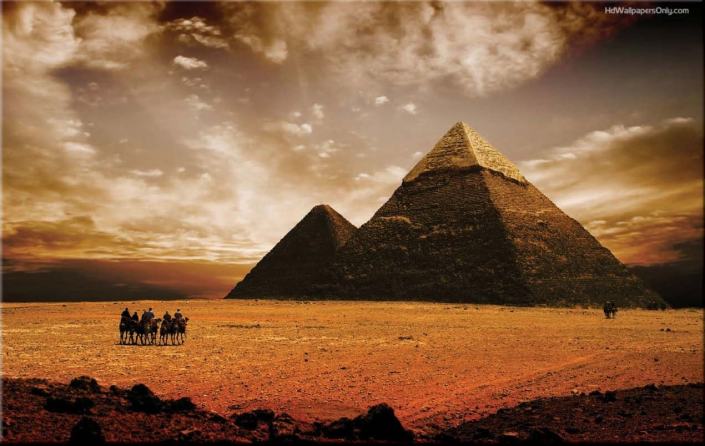

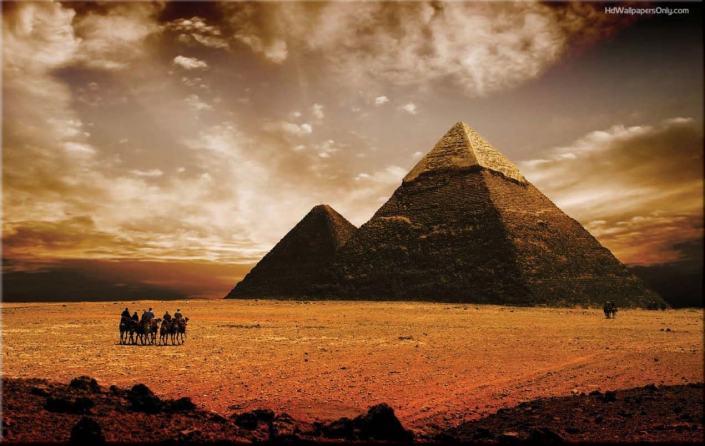

On his return to Egypt, one look at his mother’s swollen red eyes and the funereal aspect of the Palace confirmed Saif’s worst suspicions – Badr Jamal, his beloved, the person he cherished more than anything else in the world, the person whom he had struggled to attain for six long, arduous years, was gone.

Saif didn’t want to hear anything. What had happened during his brief absence from the Palace? Why? How? All that was irrelevant now. He knew what he had to do.

“Mother, please tell one of the servants to saddle up a good, strong horse and prepare me a travel bag, with enough provisions to last about a month. I’m leaving right away.”

“But, Saif!” his mother pleaded. “Don’t you see? Badr Jamal doesn’t want to be here! Let her go, Saif. She is happier with her own kind. Please, just forget about her! There is no dearth of beautiful ladies here in Egypt. Think, Saif, destiny has afforded you a second chance at a happy, normal life. Don’t gamble it away for an illusion, for a fantasy, my son! Don’t let this madness get the better of you!”

However, as before, the Queen Mother’s weeping, wailing and emotional threats had no effect on Prince Saif’s resolve. He was an obstinate fellow, and he truly did love Badr. Just as he had found his way to the magical lake in Kaghan Valley, just as he had completed the 40-day penance, the chilla, and escaped from the Ogre and the Flood with Badr in his arms, so he would bring her back from the deepest, darkest dungeons of Paristan if he had to.

“I’m sorry, Mother,” he embraced the Queen one final time before mounting his ride. “But I can’t give up without even trying.” Kicking the horse into a gallop, Saif rode away from the Palace a second time, without looking back.

Now, Prince Saif didn’t really know where Paristan was, or whether it even existed. Legends placed the kingdom of the fairies “east of Egypt”, somewhere on the mountainous border of Persia and India – and the directions stopped there.

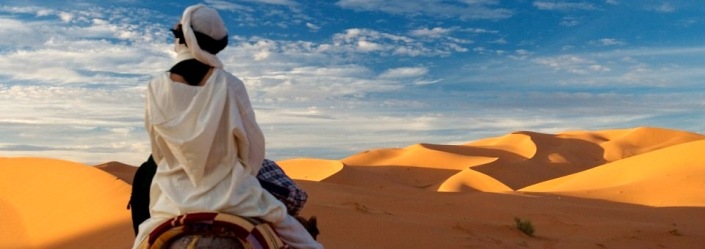

So, he travelled east for several months, crossing Sinai, the fabled rivers Tigris and Euphrates of Mesopotamia, the Great Salt Desert of Persia, the Snowy Mountains of Afghanistan, stopping time to time at some shepherd’s hut or sarai, a highway inn, to rest and refresh his supplies.

Many times he cursed himself for forgetting to carry his Sulemani topi, the magic cap bequeathed to him by the old buzurg during his first quest, which had the power to transport its wearer to any place on earth in the twinkling of an eye.

“I suppose I’m not allowed any shortcuts this time,” he grumbled.

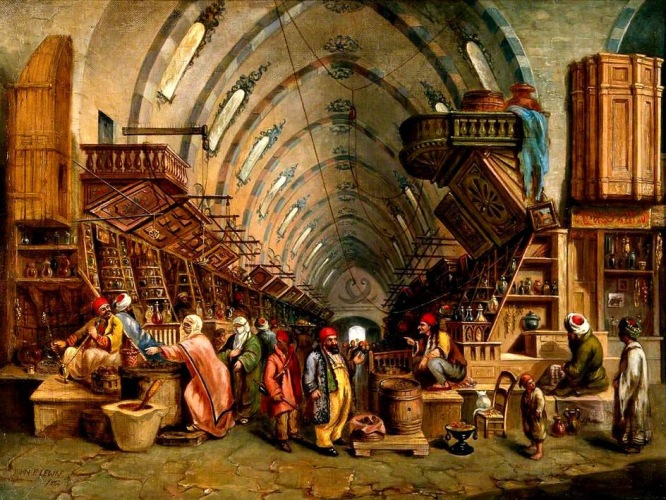

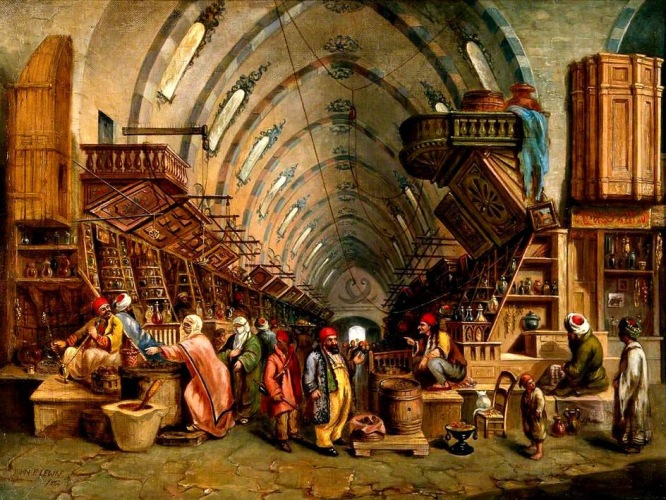

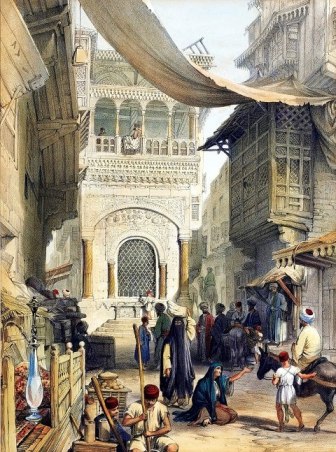

At length, Saif reached Peshawar, or Purushapura, as it was known then, the bustling western capital of the Kushan Empire, gateway to the Indian subcontinent. Merchants from all corners of the Silk Route thronged its narrow streets, hawking their varied wares in loud voices – silk, cashmere, cotton, spices, dry fruit, wine, carpets, woodwork, decorative objects of marble, ivory and jade, gemstones, weapons, secrets and stories – there was nothing you could not find in the legendary markets of Purushapura.

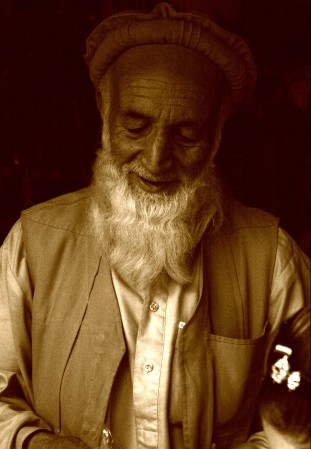

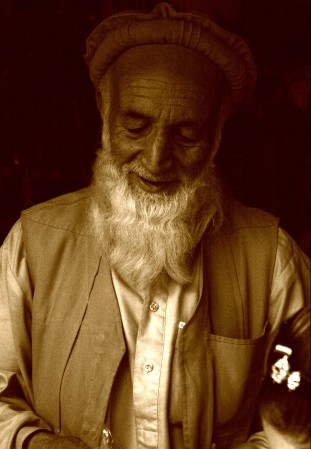

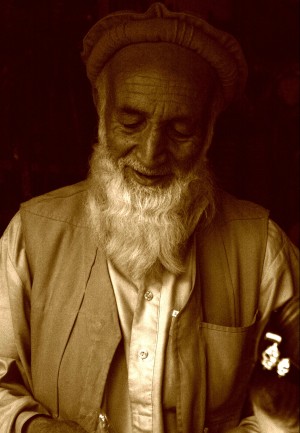

Meandering through the bazaar while his horse rested in the city’s stables, Prince Saif stopped at a chai khana, a tea shop, for a cup of the traditional Peshawari kahwa, hot green tea sweetened with honey or sugar and spiced with cardamom. Looking around the crowded little shop for a place to sit, he spotted an empty stool next to an old man with a flowing white beard, who sat calmly sipping his tea and fingering a rosary.

Prince Saif walked up to the old man, saluted him with a respectful bow, and said, “Venerable sir, would you be so kind as to allow this weary traveller to seat himself beside you?”

The old man looked up at Saif. Their eyes met, and Saif had the sensation that he knew him from somewhere; that this was not a chance encounter. “My son!” the old man smiled, eyes crinkling at the corners. “Please, it would be my honor.

“And now, tell me,” he continued, once Saif had made himself comfortable and given his order. “What brings a gentleman like yourself to this wily merchant’s city?”

Quickly, Prince Saif related to his new friend the objective of his journey: to reach the mythical land of Paristan (which, according to legend, lay somewhere in these parts), and recover his beloved Fairy Queen and true wife, Badr Jamal.

“Paristan? My dear lad!”, the old man let out a bemused chortle. “You know the reason why they call it a ‘mythical’ land? Because Paristan has no physical existence! You will not find it on any map, you will not see any signboards pointing out the way, no gates or city walls to saunter through. On the whole, it is entirely impossible for you to reach there in your present state.”

Seeing Prince Saif’s face fall in despair at this rude reality check, the old man hurried to add. “Oh, but don’t look so glum! The good news is that I can help you. Or, at least I have some things that could help you…” He started rummaging through the coarse jute sack he carried, and duly produced a tattered woolen cloak, and a short wooden staff. Saif was overcome by déjà vu.

“I’m sorry, sir,” he interrupted. “But I feel like we’ve met before. Were you ever in Egypt some years back?”

“Nonsense, son! I’ve never set foot outside the city of Peshawar,” the old man hastily brushed aside the question. “Now, listen to me carefully – for although I have not travelled much, I have learnt a great deal in the long journey of my life, from observing and talking to all the people that pass through this city. And what I tell you now may well be the only hope you have of penetrating Paristan and seeing your wife again…”

It was true. Once more, a nameless old buzurg was to be Prince Saif’s savior.

A few hours later, Prince Saif found himself riding with a caravan of merchants towards Tattoo, a small village in the kingdom of Gilgit, perched on the craggy slopes of the magnificent Karakoram mountains. The merchants, heading for China via the Khunjerab Pass, had agreed to drop Saif off at the village in exchange for his horse, a handsome Arabian steed that would fetch a weighty price in the horse fairs of the Mongolian steppe.

Saif parted with the animal with a heavy heart, but he actually had no further use for it. His real destination was 13 miles further off Tattoo, where no horse or mule tracks led; a place called Joot, today famous by its English appellation, Fairy Meadows.

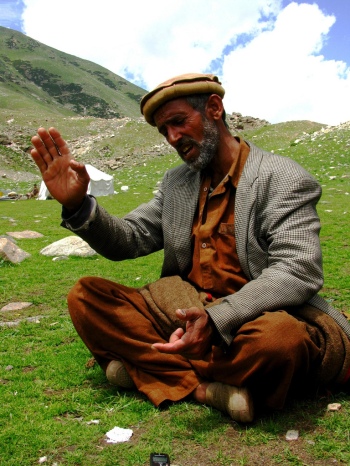

“I have never been to Joot, but I hear tell that it is a most breathtaking place,” the old man at the tea shop had recounted. “They say that a Fairy King of great power established his kingdom there, some 1,000 years ago, in the shadow of that fearsome peak Nanga Parbat, the Naked Mountain.

“Nobody lives in Joot. The locals are wary of venturing there at all because of all the stories; shepherds who went to graze their flocks and never returned; explorers, bandits, naturalists and mystics, attracted to the place by its beauty and its solitude, and never seen again. It is enchanted, they say, the abode of witches and jinns, as perilous as it is beautiful.

“This is where you must go.”

And that is where Saif had arrived, after a grueling uphill hike from Tattoo, following the old man’s directions to the letter. He stood in the middle of a vast green meadow, facing the awesome, ice-covered Nanga Parbat. Dusk was approaching, and there was not a soul in sight. All was silent, except for the gentle hum of the evening breeze amongst the pines.

Saif pulled out from his satchel the tattered woolen cloak. “Once you don this cloak,” the old man had explained, “everything around you that is made from the hands of men, will dissolve from view. Buildings, roads, entire cities, will simply vanish.

“And everything that was hitherto unseen – the realm of jinns and fairies, and all other manner of supernatural creatures – will suddenly come to light, as real, as tangible, as indubitable as that tea cup you hold in your hands.”

As for the wooden staff, the old man had said he had bought it from a wandering Jewish mendicant, who claimed that the staff contained a tiny fragment of the miraculous staff of Moses. Placed in the right hands, it had the power to unlock or open any kind of barrier – gates, doors, chains – both magical and mundane.

Standing before that gigantic mountain in the grassy fields of Joot, the very location of Paristan, all that was left for Saif to do was throw on the cloak, brandish the staff, and smash his way into the Fairy King’s palace to recover his bride.

But Saif hesitated. What if all of this was a lie? What if the old man had tricked him? And now, there he was, alone in that desolate spot with no food, no shelter, no money, not even his horse to help him retrace his steps and make the long journey home…

By this time it was almost completely dark, and a silver slipper of a moon had begun to glimmer above the jagged peaks of the Karakoram.

“Well, I don’t really have another plan, so I might as well give this a shot,” Saif thought. So, taking a deep breath, he grasped the wooden staff and wrapped the woolen cloak tightly around him….

The things that happened henceforth are better left imagined. For sometimes there are sights so wondrous, events so singular that they defy description.

Let’s just say that the old man in the tea shop had known what he was talking about!

Read Part VII, the final instalment of the story

The Legend of Saif-ul-Malook Part VI

Lake Saif-ul-Malook, situated at a height 10, 600 feet at the northern tip of the Kaghan Valley in Pakistan’s Himalayas, is one of the most beautiful places on earth. I have been there twice, the first time as a 12-year old and then in 2009, when I determined to capture some of its magic on camera and on paper, in the words of two local storytellers who relate the legend of the Lake to visitors.

It is the story of a prince and a fairy, Saif-ul-Malook and Badr-ul-Jamal – a story of love, adventure, faith, magic, suffering and betrayal – a story of the multitude of human passions.

Many different versions exist, but below is a reproduction of what the storytellers told us, with ample writer’s liberties. I hope you enjoy it!

Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV & Part V of the story

Now, you may wonder, what was Prince Saif up to at the moment Badr Jamal made her escape from the Palace in the shape of a white dove?

In fact, he was resting beneath the shade of an ebony tree deep in the woodlands of Nubia, after a fruitful but exhausting deer hunt. Eyes half-closed, stretched out on the soft green grass, he was thinking sweet thoughts about his beloved Fairy Queen, when a little white dove came and alighted on a branch above him.

It seemed to Saif that she was the prettiest dove he had ever seen – even though he didn’t consider himself a “bird person” – and he was suddenly possessed by a desire to capture her. “She’d make a nice little pet for my beautiful Badr,” he mused. So, he quietly got to his feet, picked up a net that lay amongst his hunting paraphernalia, and swiftly flung it over the bird.

But the net, as if repelled by an invisible force, bounced straight back at him, while the dove sat merrily on her perch untouched. Saif tried a second time to ensnare the bird, then a third, with the same perplexing result.

Then – and Saif could hardly believe his eyes or his ears, though he had witnessed his fair share of fantastic events – the dove turned her soft white head towards the Prince and spoke to him, in voice he could recognize among millions:

“Your attempts to capture me are in vain, Prince Saif. You can never own me. You can never possess me.”

It was Badr Jamal, of course.

“The only way to convince me of your love,” the bird continued, “the only way you will truly earn my love, is if you follow me to Paristan, my homeland. If you succeed in this, if you are able to brave the journey and seek me out in my father’s palace, among my own kind, I promise I will come back with you, as your wife and partner in life. And I will never leave your side till as long as you live.”

With these words, Badr Jamal fluttered her snowy white wings and was off, leaving Saif in a state of utter discombobulation.

On his return to Egypt, one look at his mother’s swollen red eyes and the funereal aspect of the Palace confirmed Saif’s worst suspicions – Badr Jamal, his beloved, the person he cherished more than anything else in the world, the person whom he had struggled to possess for six long, arduous years, was gone.

Saif didn’t want to hear anything. What had happened in his absence? Why? When? How? All that was irrelevant now. He knew what he had to do.

“Mother, please tell one of the servants to saddle up a good, strong horse and prepare me a travel bag, with enough provisions to last about a month. I’m leaving right away.”

“But, Saif!” his mother pleaded. “Don’t you see? Badr Jamal doesn’t want to be here! Let her go, Saif. She is happier with her own kind. Please, just forget about her! There is no dearth of beautiful ladies here in Egypt. Think, Saif, destiny has afforded you a second chance at a happy, normal life. Don’t gamble it away for an illusion, for a fantasy, my son! Don’t you let this madness get the better of you!”

However, as before, the Queen Mother’s weeping, wailing and emotional threats had no effect on Prince Saif’s resolve. He was an obstinate fellow, and he truly did love Badr. Just as he had found his way to the magical lake in Kaghan Valley, just as he had completed the 40-day penitence, the chilla, and escaped from the Ogre and the Flood with Badr in his arms, so he would bring her back from the deepest, darkest dungeons of Paristan if he had to.

“I’m sorry, Mother,” he embraced the Queen one final time before mounting his ride. “But I can’t give up without even trying.” Kicking the horse into a gallop, Prince Saif rode away from the Palace a second time, without looking back.

Now, Prince Saif didn’t really know where Paristan was, or whether it even existed. Legends placed the kingdom of the fairies “east of Egypt”, somewhere on the mountainous border of Persia and India – and the directions stopped there.

So, he travelled east for several months, crossing Sinai, the fabled rivers Tigris and Euphrates of Mesopotamia, the Great Salt Desert of Persia, the Snowy Mountains of Afghanistan, stopping time to time at some shepherd’s hut or sarai, a highway inn, to rest and refresh his supplies.

Many times he cursed himself for forgetting to carry his Sulemani topi, the magic cap bequeathed to him by the old buzurg during his first quest, which had the power to transport its wearer to any place on earth in the twinkling of an eye.

“I suppose I’m not allowed any shortcuts this time,” he grumbled.

At length, Saif reached Peshawar, or Purushapura, as it was known then, the bustling western capital of the Kushan Empire, gateway to the Indian subcontinent. Merchants from all corners of the Silk Route thronged its narrow streets, hawking their varied wares in loud voices – silk, cashmere, cotton, spices, dry fruit, wine, carpets, woodwork, decorative objects of marble, ivory and jade, gemstones, weapons, secrets and stories – there was nothing you could not find in the legendary markets of Purushapura.

Meandering through the bazaar while his horse rested in the city’s stables, Prince Saif stopped at a chai khana, a tea shop, for a cup of the traditional Peshawari kahwa, hot green tea sweetened with honey or sugar and spiced with cardamom. Looking around the crowded little shop for a place to sit, he spotted an empty stool next to an old man with a flowing white beard, who sat calmly sipping his tea and fingering a rosary.

Prince Saif walked up to the old man, saluted him with a respectful bow, and said, “Venerable sir, would you be so kind as to allow this weary traveller to seat himself beside you?”

The old man looked up at Saif. Their eyes met, and Saif had the sensation that he knew him from somewhere before; that this was not a chance encounter. “My son!” the old man smiled, eyes crinkling at the corners. “Please, it would be my honor.

“And now, tell me,” he continued, once Saif had made himself comfortable and given his order. “What brings a gentleman like yourself to this wily merchant’s city?”

Quickly, Prince Saif related to his new friend the objective of his journey: to reach the mythical land of Paristan (which, according to legend, lay somewhere in these parts), and recover his beloved Fairy Queen and true wife, Badr Jamal.

“Paristan? My dear lad!”, the old man let out a bemused chortle. “You know the reason why they call it a ‘mythical’ land? Because Paristan has no physical existence! You will not find it on any map, you will not see any signboards pointing out the way, no gates or city walls to saunter through. On the whole, it is entirely impossible for you to reach there in your present state.”

Seeing Prince Saif’s face fall in despair at this rude reality check, the old man hurried to add. “Oh, but don’t look so glum! The good news is that I can help you. Or, at least I have some things that could help you…” He started rummaging through the coarse jute sack he carried, and duly produced a tattered woolen cloak, and a short wooden staff. Saif was overcome by déjà vu.

“I’m sorry, sir,” he interrupted. “But I feel like we’ve met before. Were you ever in Egypt some years back?”

“Nonsense, son! I’ve never set foot outside the city of Peshawar,” the old man hastily brushed aside the question. “Now, listen to me carefully – for although I have not travelled much, I have learnt a great deal in the long journey of my life, from observing and talking to all the people that pass through this city. And what I tell you now may well be the only hope you have of penetrating Paristan and seeing your wife again…”

It was true. Once more, a nameless old buzurg was to be Prince Saif’s savior.

A few hours later, Prince Saif found himself riding with a caravan of merchants towards Tattoo, a small village in the kingdom of Gilgit, perched on the craggy slopes of the magnificent Karakoram mountains. The merchants, heading for China via the Khunjerab Pass, had agreed to drop Saif off at the village in exchange for his horse, a handsome Arabian steed that would fetch a weighty price in the horse fairs of the Mongolian steppe.

Saif parted with the animal with a heavy heart, but he actually had no further use for it. His real destination was 20 kilometers further off Tattoo, where no horse or mule tracks led; a place called Joot, today famous by its English appellation, Fairy Meadows.

“I have never been to Joot, but I hear tell that it is a most breathtaking place,” the old man at the tea shop had recounted. “They say that a Fairy King of great power established his kingdom there, some 1,000 years ago, in the shadow of that fearsome peak Nanga Parbat, the Naked Mountain.

“Nobody lives in Joot. The locals are wary of venturing there at all because of all the stories; shepherds who went to graze their flocks and never returned; explorers, bandits, naturalists and mystics, attracted to the place by its beauty and its solitude, and never seen again. It is enchanted, they say, the abode of witches and jinns, as perilous as it is beautiful.

“This is where you must go.”

And that is where Saif had arrived, after a grueling uphill hike from Tattoo, following the old man’s directions to the letter. He stood in the middle of a vast green meadow, facing the awesome, ice-covered Nanga Parbat. Dusk was approaching, and there was not a soul in sight. All was silent, except for the gentle hum of the evening breeze amongst the pines.

Saif pulled out from his satchel the tattered woolen cloak. “Once you don this cloak,” the old man had explained, “everything around you that is made from the hands of men, will dissolve from view. Buildings, roads, entire cities, will simply vanish.

“And everything that was hitherto unseen – the realm of jinns and fairies, and all other manner of supernatural creatures – will suddenly come to light, as real, as tangible, as indubitable as that tea cup you hold in your hands.”

As for the wooden staff, the old man had said he had bought it from a wandering Jewish mendicant, who claimed that the staff contained a tiny fragment of the miraculous staff of Moses. Placed in the right hands, it had the power to unlock or open any kind of barrier – gates, doors, chains – both magical and mundane.

Standing before that gigantic mountain in the grassy fields of Joot, the very location of Paristan, all that was left for Saif to do was throw on the cloak, brandish the staff, and smash his way into the Fairy King’s palace to recover his bride.

But Saif hesitated. What if all of this was a lie? What if the old man had tricked him? And now, there he was, alone in that desolate spot with no food, no shelter, no money, not even his horse to help him retrace his steps and make the long journey home…

By this time it was almost completely dark, and a silver slipper of a moon had begun to glimmer above the jagged peaks of the Karakoram.

“Well, I don’t really have another plan, so I might as well give this a shot,” Saif thought. So, taking a deep breath, he grasped the wooden staff and wrapped the woolen cloak around him….

The things that happened henceforth are better left imagined. For sometimes there are sights so wondrous, events so singular that they defy description.

Let’s just say that the old man in the tea shop had known what he was talking about!

Read Part VII, the concluding part of the story

Kalash Valley, Pakistan

In May 2012, I was lucky enough to take what was truly a once-in-a-lifetime trip, to a remote corner of the Hindukush mountains in northwest Pakistan. Near the town of Chitral (at an elevation of 3, 700 ft), and a 26-hour drive from my hometown in the plains, Lahore, the Kalash Valley is home to a small but unique tribe of people, the Kalash, “the wearers of the black robe”, Indo-Aryans who settled among these rugged peaks thousands of years ago, and have held on to their ancient beliefs, language and customs since then, while the rest of Central Asia assimilated to Muslim culture.

We visited the Kalash village of Bumburait at the time of their annual Spring Festival, “Chilum Josh“, and got the chance to see the iconic Kalash in all their pomp and glory. Their population, which was once fast declining due to forced conversions, is now on the rise; protection by the Pakistani government and growing local tourism has helped them maintain cultural independence.

Let this album take you on a photographic journey, from the windswept highways of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province to the bustling streets of Chitral town, to the vibrant, beautiful faces of Kalash women and the windy, shadowy alleys of their hamlets on the hill.

Many thanks to the brilliant folks at Adventure Travel Pakistan for organizing the trip!

Costa Rica Day 3: Ziplining in a Cloudforest, and a Hostel Hunt!

September 5th, 2010

Santa Elena / La Fortuna, Costa Rica

We woke up to the sound of sizzling eggs and childish chatter in Spanish. I rubbed my eyes and looked at the forest-green walls, the lacy white curtain spilling light, the gigantic tiger-print fleece blanket on the bed. “Where am I?”

At a hostel in Santa Elena, of course, hours away from one of the most thrilling activities Costa Rica had to offer, in one of the most pristine cloudforests in the world!

We hurried down to the kitchen, where the hostel-keeper Ronny’s wife was cooking us up a hearty breakfast, while her two adorable children Daniel and Jasmine capered about in their sky-blue school uniforms. Soon, a Turismo van arrived to take us to the Selvatura Adventure Park for our canopy tour.

Selvatura Park is located on 1, 200 acres of virgin cloudforest in the heart of the misty Monteverde Reserve, founded in 1951 by a group of American Quakers. There are no walking or hiking trails traversing the forest, so the only way to see it is through a network of hanging bridges, or on horizontal cable-trolleys called ziplines. Ziplines have been used as a method of transport in remote mountainous regions (including northern Pakistan and India) for over a century , but the modern canopy tour was developed by naturalists in the 1970s as an eco-friendly way of exploring rainforest.

As our guides geared us up with harnesses, gloves and helmets and hammered out instructions, I had that familiar fluttery feeling in my stomach – What if I get stuck mid-way on the cable? What if I lose my balance and topple upside-down? What if I scrape my hand on the steel and it starts to bleed?

“Really, you’re the last person who has the right to be scared, you’ve jumped out of an airplane!” my husband Z scolded me. I think I was only pretending to be scared though – just so I’d be mentally prepared in case something did go wrong.

But once we were up there in the treetops, on the first platform, and with one push I was sent zooming along the cable, comfortably seated in my harness, lush forest below and sunny skies above, there wasn’t a happier person than me in Monteverde.

I just couldn’t control the smile on my face. It was so, so, so much fun. The moment I reached the other side I couldn’t wait to do it again. We rode 15 different cables in the span of 2 hours, over various lengths and heights – sometimes brushing past leaves and branches in the thick of forest, sometimes a kilometer above the canopy, stretching green till the horizon. On the two longest cables (650 and 700 meters), they sent you in pairs, so me and Z rode together, whooping at the top of our lungs the whole way!

Back in Santa Elena town, we were famished (as usual), and made our way to a red-painted soda called Maravilla, recommended to us by the hostel-keeper Ronny. We ordered a typical Costa Rican lunch, casado, which consisted of the basic Latin American fare of rice and beans, with a portion of meat-in-gravy, fried plantains and salad. I polished down my casado con pollo with a tumbler of fresh Tamarindo – imli juice! – and followed it up with dessert at the beautiful Morphos restaurant.

After lunch, we said goodbye to Ronny and family, checked out of Sleepers Sleep Cheaper, and made the journey back to La Fortuna, where we had other activities planned over the next two days. We’d made reservations online at a local hostel, and the jeep was going to drop us there directly.

But as the jeep trundled past La Fortuna’s cheerful downtown and twisted into a pot-holed back alley, and colourful facades turned into tin-roofed shanties, I said to Z with some foreboding, “I have a bad feeling about this place!”

Before we knew it, the jeep was gone, leaving us in the pouring rain at the porch of a dingy grey house with a sputtering tube-light and an emaciated, bulgy-eyed, 5ft-high man at the reception. “Bienvenido,” he rasped with a crooked grin, “Plees check een hee-yre”. I watched with horror as Z lifted the pen and wrote down his name in an empty register.

The little man then took us around to our “room”, opening a creaky door to a prison cell from Alcatraz – damp and windowless, with paint peeling off the grey walls and a spindly bunk bed covered in grey sheets that looked like they were last washed in 1968.

I stared at Z. “No – way. Nooo way!” He gave me a helpless look. “I know this isn’t very pleasant. But what can we do? We’ve already checked in!”

“It doesn’t matter!” I pressed. “Just make up some story, tell him we have friends at another place, and want to stay with them.” I was conveniently excused from the dirty work because I didn’t speak Spanish and Z did :P

Z came back five minutes later. “I told him. He wasn’t very happy, but I have a feeling this has happened to them before!”

Laughing with relief, we strapped on our packs and set off in the rain towards downtown La Fortuna, to hunt for a decent place to pass the next two nights.

There wasn’t a lack of choice – the main street was strewn with them. We first walked into a beautifully designed, leafy, woody, two-storeyed hostel, comfortable, clean and cheap rolled into one – perfect, really, except for the manic old American hippie who ran it . “But what don’t you like about this place? What? What?” he pleaded when we told him we wanted to look around a little more. “But why would you want to do that? Why? Why?” he almost shrieked.

I looked at Z again – another one of those “looks” – and, finding some excuse or other, we extricated ourselves from the desperate old fogey and ventured on.

A few blocks down, we passed by a place called Hotel La Amistad, where a rotund, smiley-faced man signaled us in through the glass door. “You looking for a place to stay? Won’t find a better deal!” He introduced himself as Salim from Nicaragua, the proprietor of Hotel La Amistad. “You can look around all you want, my friends, but I bet you’ll come right back here!” he winked.

And Mr. Salim – named after an Arab friend of his father’s – was absolutely right. I don’t know if it was his exuberance or the open, inviting look of the hotel, a courtyard surrounded by rooms with hammocks and easy chairs outside every door, but we did’t even bother looking anymore. We were sold!

After a light dinner at the Lava Lounge restaurant across the street, we turned in – and was I glad to be sleeping in the airy room and freshly-laundered white sheets of La Amistad instead of on the bug-infested coffin-shrouds in Alcatraz two streets away ;)

Next week, Day 4: Cano Negro River Safari!

![Badr emerges from the water [Artwork by Liza Lambertini]](https://manalkhan.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/badr-fullmoon.png?w=705)