Life

Farewell, fond 20s! I’m ready to move on

Why do we expect so much of life, and of ourselves? Why do we choose to be unhappy? Some questions pondered, some lessons learnt, some wisdom received

Published in Dawn Blogs, May 26th 2015

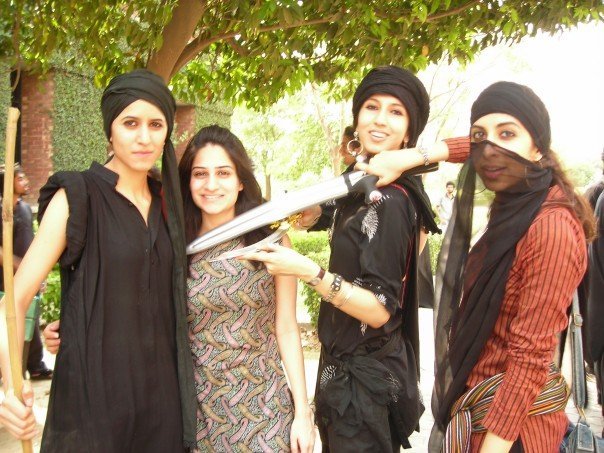

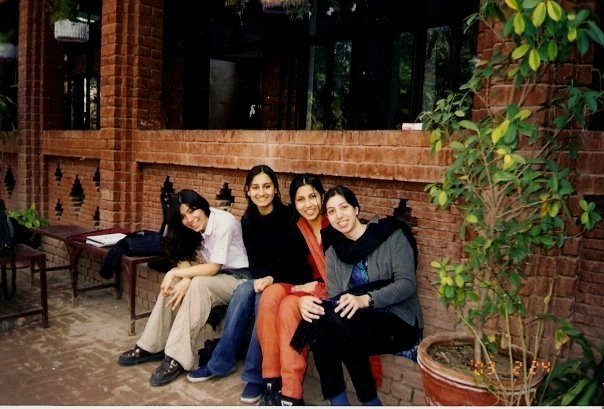

Once, when I was an undergraduate at LUMS in Pakistan, we were asked to create “future” CVs for ourselves, imagining where we would be 10 years down the road. According to my calculations, by age 30 I would be an acclaimed international affairs correspondent with Al Jazeera TV. I would also be a certified yoga instructor, the author of an award-winning collection of short stories, and the co-director of a charity school in Pakistan. I would have trekked to the base camp of an 8,000-meter peak (if not summited the peak itself), and I’d be speaking 5 languages like a native, or as we say in Urdu, farr farr.

A few weeks ago, I celebrated my 30th birthday. And looking back at that smug, overambitious piece of paper (I still have a copy), what do you suppose I felt? Disappointment, at falling short on pretty much all of my grandiose goals? Guilt, for being lazy, for not doing “enough”, for not “living up to my potential”? Anger, at myself, at people around me, at the circumstances that thwarted my legendary ascent to that 8,000-meter peak and to age 30?

No. I only laughed! Frankly, I couldn’t give a baboon’s butt about goals, objectives, achievements that you could enumerate on a CV, that you could neatly check off from a “bucket list” and be done with. I didn’t care about what I may have expected from life 10 years ago, 5 years ago, even 1 year ago.

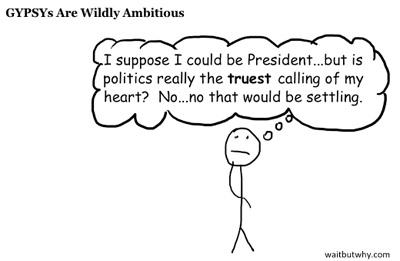

I used to care, I used to care a lot. During my 20s, I was beleaguered by that pervasive pressure to “achieve”, all too familiar to us Millennials. Often times, we weren’t even sure of what we wanted to achieve; it could be an important position at a multinational corporation or a big bank, it could be starting our own business, running an NGO, getting a PhD, “making a difference”. Yes, what we wanted most of all was to make a difference, to “change the world”.

I am not a superhero!

I stopped thinking like that some time ago, and it was a conscious decision. I stopped thinking that I could change the world.

That’s not to say that I became cynical. I just realized that I, as one individual, did not have the power to change or “save” the world. I couldn’t eradicate poverty. I couldn’t stop wars. I couldn’t ensure that every child on the street went to school, that no woman was raped by any man. I couldn’t put an end to meaningless violence, I couldn’t reverse global warming.

I couldn’t carry through any of this in my own hometown Lahore, let alone the entire world. The world was chockfull of problems, had always been, and would always be. It was the sorry fate of humankind. And to think that you were somehow “special”, that you could clean up a mess that was centuries, millenia in the making just like you’d solve a nifty Math problem, was downright arrogant.

I couldn’t carry through any of this in my own hometown Lahore, let alone the entire world. The world was chockfull of problems, had always been, and would always be. It was the sorry fate of humankind. And to think that you were somehow “special”, that you could clean up a mess that was centuries, millenia in the making just like you’d solve a nifty Math problem, was downright arrogant.

Once in a while, perhaps once in every generation, somebody exceptional came along. Extraordinary people who, by dint of birth, effort, circumstance, and some serendipitous conjunction of the stars, did extraordinary things. The world’s heroes and heroines, revolutionaries and prophets, thinkers and humanitarians, inventors and scientists, artists and writers, whose names we all read in history books. I don’t suppose that any of these great people ever planned on changing the world, or becoming famous. I don’t suppose they wrote about it in their college applications, or scribbled it on their “bucket lists”.

I think they were just going about their lives, one day at a time, doing whatever it was they loved and believed in – not expecting any accolades or honors, not preoccupying themselves too much with “results”, just following their intuition, being themselves.

That’s one thing we all have the power to do; be ourselves. Improve ourselves, and consequently, have a positive effect on everything around us.

It could be something as simple as, say, recycling your trash. Giving a sandwich to the homeless man on your street. Holding open the door for an old lady at the metro station. Lending an ear to a friend who’s had a bad day. Giving somebody an unexpected gift. Teaching somebody a skill, or learning something new yourself. Making friends with somebody from a different religion, ethnicity, culture and country. Making the world a more tolerant, a more peaceful, kinder and happier place by embodying those qualities in your own person.

That was, realistically, the best I could do, and it was enough for me. There was no point in beating yourself up over “failed” ambitions or irrational expectations, neither your own nor those of others.

I am not a martyr or a saint!

The expectations of others, or “What will people think!”. We’ve all been oppressed by them – from something as trivial as buying the “right” gift for a birthday party, “having” to attend a cousin’s friend’s brother’s wedding or wearing the “right” outfit to a family lunch, to being emotionally coerced into a marriage by your parents, putting up with an abusive husband, sticking with a job that daily sucks the life out of you. Why? Because that’s what you’re expected to do. That’s what a good, responsible, respectable man or woman does. A good, responsible, respectable person makes everybody happy – everybody except himself. A good person is a martyr.

Now, there may be people out there who would gladly suffer all these societal tortures, and many more, out of a genuine sense of duty, or out of pure selflessness. But most of us are not like that. We are not selfless. We are not saints. We may like to think we are, but deep down inside, where nobody can hear our true thoughts, we ask ourselves: “Why am I doing this? Is it worth it? I’m fulfilling all my ‘duties’, but why am I still so miserable?”

There’s something perversely romantic about misery, the notion of sacrificing your life for the sake of others, for your children, parents, friends, your community and country, without a thought to your own wishes and desires. Whether or not you enjoy being cast in that role, society will definitely love you for it.

On the other hand, society will not take kindly to seeing you happy. That’s just shameless. And, if you insist on being so brazenly optimistic, then at least pretend to have something to gripe about!

This kind of thinking is typical among desis (South Asians), and I was done with it. If your actions didn’t spring from love or genuine kindness, if your only motivation was to “live up to” some vague ideal or ill-conceived expectation, the fear of what people might say, then those actions were worth very little. It was better to spare yourself and the people around you the charade. The fact was, you couldn’t make anybody happy, truly happy – not your parents, not your partner, not your kids nor colleagues, nor posterity – unless you were happy and fulfilled yourself. It was not always the simpler choice; oftentimes, it was easier to be miserable, it was easier to be a doormat than to stand up for your inviolable right to happiness. But it was a choice you made.

I am not a victim

So far, I’ve led a pretty privileged life. I’ve never known hunger, or homelessness, or direct violence or abuse, none of the unimaginable hardships that form reality for millions of people around the world. All of us, sitting at our laptops or scrolling down our smart phones, are familiar with the ordinary struggles of human existence – death and sickness in the family, relationship troubles, financial crises – but nothing as shattering as the experience of a child in a war-torn country, a family who has lost everything in a natural disaster, the victim of racism or religious persecution, a refugee, an addict, a prisoner, a slave.

Given the enormous advantages that we already have, there is really no excuse for us to feel sorry for ourselves, or vainly blame others for our own unhappiness. We are not victims, and we are certainly not helpless. We are lucky enough to be able to choose what we want to do, how we want to live. We are lucky enough to be able to make our own decisions, chart our own priorities, control the course of our lives with some degree of certainty (putting aside a percentage for qismat, of course). It could be, for example, choosing to spend on a holiday rather than a new piece of jewelry, or exercising instead of watching TV. Or it could be something more far-reaching, like deciding to move to a new country, taking on a new job, having a baby.

The bottom line is, we all are blessed. We all have gifts, we all have dreams, and most importantly, we all have volition. We just need to muster up the courage to pull those tricks out from our magic bags and put them to use, in spite ourselves.

I am rather insignificant

So, what have I learnt about life after 30 years? It doesn’t seem like a whole lot, even by earthly accounts. In the universal scheme of things, it’s embarrassingly negligible…

But, keeping things relative, as of now I feel that life is really about living. It’s not about achieving lofty goals, building lofty monuments, racking up positions, bank accounts, cars and TVs and diamonds. It’s not about pleasing others, being a hero, a saint or a superstar, devoting your life to any one cause.

It’s about finding contentment, finding beauty, finding peace in the little things. The day-to-day achievements, the seemingly mundane. You learnt a new word today. You tried a new dish. You finished an assignment before deadline. You took your kids to the movies. You caught up with an old friend. You explored a new neighborhood. You danced under the trees.

Your expectations of yourself need not be grander. Yes, you may wish to write a book one day, or set up a charity school – I know I do! I haven’t forgotten those dreams. But I’m no longer in a rush to accomplish them, nor am I going to let them dictate or frustrate my present.

I look…different!

There was a time when I’d walk out of the house with a squeaky clean face and just a dash of kajal in the eyes, ready to go to college, a dinner or a wedding; now, I use makeup on a regular basis. I even wear lipstick, something I found utterly loathsome at 20! The salon girl makes it a point to count out the growing number of white hairs on my head every time I go for a trim, shaking her head disapprovingly, “But why don’t you dye???” I find myself flipping magazines at various doctors’ clinics much more often, thanks to an array of itinerant physical pains. I’ve become more attentive to what I eat, trying my best to choose a salad or a piece of fruit over a cupcake or a toast slathered with butter and marmalade; before, I couldn’t be bothered about the lumps of sodium in ChinChin Chinaman’s hot and sour soup, or the pools of grease in the LUMS cafeteria chicken karhai.

Then there are the inner changes, the ones you can’t really see; I feel happy, but in a calmer way. I’m not in a hurry to go anywhere, do anything, be anyone. I don’t care as much of what people think of me, and I’m a lot less concerned about offending somebody over a nicety. The smudges of shyness and self-consciousness that I had retained from teenage into my 20s have all but dissipated – and life is so much easier without them! I avoid comparing myself with others, I try not to be overly self-critical (a family trait), and most of all, I remind myself to be grateful, and not take life too seriously.

And what of the idealistic goals of that fictional 10-year old CV? Well, I didn’t fall off the mark entirely when I made those predictions. So I’m not a correspondent with Al Jazeera TV, but I did work at Democracy Now, the most excellent independent TV news program in the U.S. (in my opinion!). I’m not a certified yoga instructor, but I am an uncertified Bollywood dance teacher! There’s no collection of short stories (let alone award-winning), but there is an in-progress research project and an intermittent blog. I’m not the director of any charity, but I basically do volunteer work for a living, from museums to bookstores to archaeology pits. I’d say I’ve got 2 languages down in the farr farr category, with a 3rd one in the works; and, instead of summiting the base camp of an 8,000 meter peak, I chose to throw myself out of a perfectly good airplane 1,000 meters in the sky (you do some ridiculous things in your 20s). So, all in all, I’m pretty satisfied with the 30-year report card!

As should you be with yours! There’s no need to feel despondent and have regrets about what you could have done and didn’t do; and there’s no need to panic that your “best years” are flying by so you better make “the most” of them. With good health and a little bit of qismat, every year, every day can be your best, if decide to make it so.

12 things this Pakistani girl loves about Spain

Published in Sunday Magazine, September 29th 2014

It’s been a full year since our peregrination to Madrid (hard to believe!), and I think I’ve come a long way from those initial months of confusion, misplaced nostalgia, and sometimes plain despair (among other unproductive emotions that beleaguer you at every move!)

For one, I can (sort of) speak Spanish. I’ve made friends. I even have a (sort of) job! I can navigate the city fairly well – I’ve visited the doctor, the dentist, the real estate agent, the immigration bureau, even the police station (don’t ask), without any major communication disasters occurring. I’ve traveled around the country a fair bit. I’ve been taken for a local and given directions to lost tourists (score!). And, though there are obviously bothersome things about every country, I find myself quite enamored of Spain. Here are just a couple of reasons why, in no particular order!

1. Hot Chocolate

It’s traditional to begin AND end the long Spanish days with a cup of thick, intensely dark hot chocolate, often with a side of churros (long, deep-fried dough pastries for dipping). Some chocolaterías, like the 19th century San Ginés in historic Madrid, are open 24 hours – so you can amble down for an indulgent treat any moment it grabs your fancy. A chocoholic like me can’t complain!

2. Festivals

Spain does festivals like nobody’s business, second only to India when it comes to the sheer number of public celebrations and commemorations in the country. The most spectacular among these is Semana Santa or Holy Week (Easter), curiously similar to Ashura in Muslim countries, where participants in full costume re-enact Jesus Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection over the course of 7 days with elaborate floats, music, and in some places, self-flagellation. There are festivals dedicated to saints and to devils, to horses, flowers, geese, tomatoes, bulls, newborn babies, even paper-mache monsters!

3. “Harem Pants”

You can literally roll out of bed in a printed shalwar and T-shirt and step onto the streets of Madrid or Barcelona perfectly in sync with fashion. Harem pants, as they are known in the West, are a perennial component of the trendy Spaniard’s wardrobe – the baggier, the better! Could “dressing up” get any easier?

4. Beards & Piercings

Dark-bearded men and nose-studded women are as ubiquitous on the streets of Spain as in Pakistan, partly thanks to hipster trends. So you can comfortably sport your preferred style of facial hair (if you are a man), or a nice twinkly nose piercing (if you are a man or woman), without the least fear of being eyed suspiciously and stereotyped “terrorist”, “punk”, or, most annoyingly, “oh-so-exotic!”.

5. Moorish Spain

Stroll under the Damascene arches of the oldest surviving mosque in Europe, the Mezquita of Cordoba, dating to 785 A.D. Wander through the ethereal Nasirid Palaces of the Alhambra in Granada, the Muslims’ last stronghold in Spain. Treat yourself to a milky Té Pakistani in an evocative tetería. There is an undeniable romance about al-Andalus of yore, and for some romantic reason, you feel as if you share a part of its history.

6. Flamenco

Spain’s most iconic song & dance form has roots in North African and Gypsy (“Roma”) culture. Roma people were originally from the Indian subcontinent, and migrated to Europe about 500 years ago. The mix of cultures produced a unique dance that emphasizes not feminine delicacy and beauty, but feminine power and strength – stomping, sweating, shouting and all! You gotta love it.

7. Olives

Aceitunas have been one of the healthier additions to my diet since moving to Spain. With the cultivation of olives dating to ancient Roman times and improved upon during the Moorish era, Spain today produces about 300 varieties of olives in all shapes, sizes, tastes and textures. Next to my mother’s hand-cured green olives from a family orchard in Pakistan, juicy Spanish olives stuffed with garlic are the yummiest snack I could ask for!

8. Spanish Idiom

Express yourself like a true Pakistani in the Spanish language! From Ojalá (Inshallah), Venga! (Chalo), Que? (Kya?), Hermano (Bhai / Yaar), Adiós! (Khuda Hafiz!) even Ala! (Hai Allah /Allah Tobah!), the flavor of spoken Spanish is remarkably similar to Urdu or Punjabi, with many words derived from Arabic.

9. “Laid back” – in a good way!

Spaniards have a bit of a reputation for laziness, but from what I see, they work as much as any of their counterparts in the Western world, without the uptight fastidiousness. So, yes, a waiter will probably take 20 minutes to come and take your order, but he or she will also not pester you to pay or vacate your table until you are ready to leave, whenever that may be! Yes, most administrative offices, pharmacies and private businesses take a 3-hour lunch break, but when they serve you, they are always friendly, accommodating, and seem to genuinely enjoy their job, no matter how mundane it may be. I think the system works!

10. Rabo del Toro (Oxtail Stew)

The Spanish version of a Pakistani Aloo Gosht or Nihari – succulent bull or oxtail, slow-cooked in its own stock and a rich gravy of onions, tomatoes, potatoes and other vegetables and spices, till the meat literally falls off the bone. Scoop it up with crusty pieces of bread just like you would do with Naan or Roti back home – riquísimo!

11. Nightlife – Ronaq!

Go for a walk in any barrio or neighborhood in the city center at 1:00 am on a weeknight, and find warmly-lit restaurants and cafes bubbling with customers, street performers juggling fire on the sidewalks, couples strolling along with little children in tow, boisterous touts trying to lure you into nightclubs. And the weekends? Soundproof windows recommended if you want to get any sleep! No matter the unemployment and fiscal crisis, the Spaniards know how to have a good time.

12. Compliments!

In most places in the world, being addressed as “pretty girl” (guapa), “little girl” (niña), or “queen” (reina) by a complete stranger would be considered offensive, and probably make you uncomfortable. Not in Spain! Shopkeepers, street vendors, waiters, passersby, men and women can call you all those things in Spanish without a trace of sleaziness. Now why wouldn’t that make you feel good? Add to that their beaming smiles and ready greetings, it’s impossible not to feel happy and welcome in this country.

How to Make Friends in a New City – Tip #5

- No te preocupes! Don’t worry! Let the universe do its thing!

This is something I’ve learnt along the course of my somewhat peripatetic life the past 6 years: sometimes, people (and opportunities) fall into your lap in the most unexpected, unlooked for way; and these congenial little windfalls may be the best things that happen to you in your new home.

I remember a certain day in Ithaca, New York, where Z and I had moved right after getting married. Z was in class at Cornell, and I was busy cleaning, unpacking and ‘nesting’ in our new apartment, a ground-floor portion of a typical East Coast colonial house, when our gritty old landlord Carl ambled up to the front door, dressed in his customary red plaid shirt and classic blue jeans. “Hey there!” Carl hollered, “I wanted to introduce you to these nice folks,” he gestured towards the smiling young couple that followed him. “They’ve just moved to Ithaca from Mexico, and are thinking of renting from me as well!”

That was the first time I met Elsa & Silvano. Though we only spoke for five minutes, standing in the porch of Carl’s yellow-painted dollhouse, and thought they didn’t end up renting from him after all, they became our closest companions the 9 months we spent in Ithaca, and we still count them among our dearest friends.

So, just like that, someone may chance to cross your path, and you’ll hit it off with them like you never imagined. Maybe a friend of a friend puts you in touch with somebody they know who happens to live in the same city; and you turn out to be kindred spirits, Anne of Green Gables-style. Or maybe another like-minded soul, going through the same experiences as you, discovers you and contacts you through your blog!

I find it so interesting, how these connections are made – magically, almost – bringing complete strangers together through no deliberated effort. So, if you ever find yourself lost, alone and friendless in a new city, wondering why on God’s earth you ever transplanted yourself in the first place: don’t worry! It takes time for a plant to adjust to new soil, a new atmosphere. But once it gets over the wilting, drooping, moping period – ‘transplant shock’ in botanical terms – it thrives. In fact, if you don’t keep an eye, it may even start merrily taking over your garden, and you won’t know what to do! :)

Happy New Year from Madrid! Here are some photos we’ve taken of the city’s squares, streets and public spaces.

Read Tip #1,Tip #2, Tip #3, Tip #4, and the introductory post of this series!

How to Make Friends in a New City – Tip #4

- LANGUAGE EXCHANGE

Language exchange, or intercambio, is a popular (and free) method of learning languages in Spain. There was a plethora, a veritable sea of Spaniards out there, my Spanish teacher told me, who were desperate to find a sympathetic English-speaker to practice their hesitant conversational skills with. English is taught in Spanish schools as an optional second language, but in the most pedantic way possible, so that somebody who has “studied” English for over 10 years can barely formulate a coherent reply to a “Hi, what’s up?”

Kind of like how we were taught Pakistan History in secondary school. Once, in a surprise test, the teacher asked us to write an essay comparing the achievements and successes of two of Pakistan’s Prime Ministers. I started with the conventional introduction (memorized from the textbook, of course), ended with the conventional conclusion (we knew it like we knew our multiplication tables), and filled in the middle with a fictitious story, sprinkled with song lyrics. The result? 9/10, if you please, and a “Well Done!”

But, coming back to Spain – intercambio sounded like the perfect arrangement for me. Not only would it help my Spanish, I would also have somebody to chat with over a cup of coffee – that nameless, shadowy, friend-like figure I wanted so badly in Madrid! All I had to do was find somebody…

I immediately set to work. I went to tusclasesparticulares.com, created a profile, and posted an anuncio, an ad, stating my particulars in a cheerful, casual tone, and offering my stupendous English-speaking ability in exchange for un poco ayuda with my abysmal Spanish. We could meet in a cafe, or a park, como tu prefieres. I enjoyed photography, and writing, and meeting new people. Hoped to hear from you soon!

It almost felt like online dating, or shaadi.com. I went to bed that night with a flutter of excitement in my heart. Who would read my ad? Who would reply? Would I like them?

But nothing could have prepared me for the deluge of emails I found in my inbox the next morning; messages from men and women of all ages, all walks of life, from the city of Madrid and beyond, asking for my hand as their intercambio partner.

I was terribly flattered – and a bit overwhelmed. There were just too many fish in the sea. I needed to focus, start being selective, separate the wheat from the chaff, as they say. So began Step 2 of the intercambio-partner-hunt: carefully reading every ‘applicant’s’ email to divine something about their personality (Does she sound too serious? Does he sound sleazy?), stalking them on Facebook and Twitter, examining any photos that turned up. Some applications were discarded immediately; for example, the 38 year-old pianist who sent me a tea-stained studio portrait of himself in a brown fedora and brown tweed suit, or the 18-year old Economics student whose entire album of Facebook profile pictures consisted of duck-faced selfies.

After I had completed the first shortlist, I sent an email to each selected ‘applicant’, requesting, somewhat discreetly, a 200-word personal statement: “So, what do you do? What have you studied? What are your hobbies? I think it’s important, for a successful intercambio, that we share some interests, don’t you agree?”

When the replies started coming in, I made a second shortlist. Emails that included the words “books”, “languages”, “cinema”, “outdoors”, “museums” and “dogs”, for instance, were directed to the “Yes” Folder, while emails with the words “motorbikes”, “shopping”, “clubbing” and “pop music” were immediately relegated to the “Rejects” Folder (no offense meant to motorbike aficionados, shopaholics and Katy Perry fans, it’s just that, I wouldn’t know what to say to you!).

Now came the hard part: the actual, face-to-face meeting! I made appointments with the final 10 candidates, to meet them at a public square or coffee shop – blind dates, really. We barely had any idea of what the other person even looked like. And anyone who has been on a blind date will know that the first meeting was absolutely crucial. It could make or break the budding relationship. Either you liked the person, or you didn’t. Either you wanted to see that person again, or you didn’t.

Sure, I had my share of disappointing dates. Some people, intimidatingly interesting on paper, were plain boring in real life. Some people lacked energy or enthusiasm (for which I always tended to overcompensate, resulting in the peculiar condition know as the “laughing headache”), and some people just didn’t speak. In these cases, I found silence to be the best way to politely “end” things. In other cases, I was forced to lie: “I’m sorry, I’ve found a job as a dogwalker and don’t have time to do intercambio anymore!”

But, with some people, it just clicked. Conversation flowed naturally, there was laughter on both sides, and you were perfectly at ease after the first five minutes. I met a medley of memorable characters – a lawyer, a psychologist, a biochemist, an astrophysicist – all more or less my age, warm, openminded, hardworking people from different parts of Spain, who somehow found time to meet me for intercambio in their 10-hour work days. Finally, I could stop! Stop the endless virtual interviews, the awkward blind dates, the cruel but inevitable rejections!

So, has language exchange made me fluent in Spanish? No. Has my Spanish improved? I’d like to think so, yes. But more importantly, I’ve found Spanish friends, and through them, an insight into Spain. They tell me their views on love, marriage, family, religion, politics, and I share with them my experiences growing up in Pakistan and living in the United States, two completely different worlds about which they are equally curious. It’s strange how two people, complete strangers in one moment, can go to speaking about their personal lives with the air of old friends in the next. It is something that happens always with expats – maybe out of the boldness that comes with being a foreigner, or maybe out of our intrinsic need to trust, to talk, to confide in a palpable human being, in a place where there are no givens, where we must build our life up from the ground.

Read Tip #1,Tip #2, Tip #3, Tip #5, and the introductory post of this series!How to Make Friends in a New City – Tip #2

- JOIN A RECREATIONAL CLASS

When you’re not a full-time student, nor do you have a “’real” job, nor any family in the city where you live, you end up with a lot of free time on your hands – which can be perfectly utilized by learning something you’ve always wanted, but never really got a chance to do. For instance, crocheting, or Thai kickboxing. Sushi-making, or calligraphy, ventriloquism, or, better yet, magic!

That something for me right now is Middle Eastern dancing. I carry my black coin-belt around with me wherever we go, and Google down a dance class whichever city we happen to be in. Apart from the fact that I love to do it, it’s also a good way of meeting people – perhaps even a potential friend, whom you are assured of having at least one thing in common with!

So, with all this in mind, I joined a classical Egyptian dance class in Madrid, taught by a half-Egyptian, half-Paraguayan, Spanish-born woman called Yasmina, who has been dancing professionally for 20 years.

On my first day, I arrived late. I had gotten confused when exiting the metro station, and walked in the wrong direction for a good ten minutes. “Darn it,” I thought, when I realized my (usual) mistake. “There’s no point of going to the class now. There won’t be space for me anyway!”

I was envisaging, of course, the type of dance classes I had attended in Berkeley and New York; a normally tiny square-shaped room packed to the seams with a variety of serious-faced girls in intimidating-looking leotards; the teacher (whom you could barely see) hollering instructions, bootcamp-style, over the pounding music; and me in the back row, whacking my hands into the wall every time we did snake arms, or getting trampled on by Rubber Girl next to me at every grapevine turn.

But here, when I scrambled into class, huffing and puffing, with a “Lo siento-ooo!”, I’m sorry-yyy, on my lips, I was shocked to find myself in a 60 ft x 30 ft, hardwood-floored room, glistening mirrors on not one but three sides, nicely framed posters on the cool blue walls, and Yasmina the teacher with two students – dressed in comfy track pants and T-shirts – quietly doing some stretches.

“Is the class already over?? Has everybody left??” I asked, bewildered.

No, they were just about to start! “Solo nosotras,” Yasmina smiled, flicking on the music. I couldn’t believe it! What joy! What pleasure! What a wonderful feeling to sway about freely my unusually long limbs without colliding into an animate or inanimate object at every move!

There were even times when the other two students didn’t show up, and it was just me and the teacher, whom I could pester with complaints and questions to my heart’s content (“But why can’t I do the sideways shimmy? Why? Why doesn’t it look as good as yours?”) On the downside, nobody in the class, including the teacher, spoke any English, so we had to suffice in our communication with gestures, intonation and a range of facial expressions. The other girl in the class, who was my age, seemed nice, but I could not glean much about her from my limited Spanish and her non-existent English save that she worked at a pharmacy, loved leopard print and Khaled.

On the upside, one of the first things I mastered in the Spanish language were parts parts of the body – rodilla, tobillo, talón, cadera, codo, muñeca, cuello – much to my Spanish teacher’s amazement when we came to study that chapter in class. You bet, I knew them body parts like a doctor. And, generally, I became known amongst the nice ladies at the dance school as the funny “American” girl (because I spoke English) who laughed a lot, seemed genuinely excited to be in Spain (unlike the Spaniards themselves, who were desperate to leave), and who continually invented new ways to bungle their language – which they didn’t seem to mind at all!

Read Tip #1, Tip #3, Tip #4, Tip #5, and the introductory post of this series!

How to Make Friends in a New City – Tip #1

- JOIN A LANGUAGE SCHOOL

Now, this may seem like an obvious thing to do if you move to a country where you don’t speak the local language (and no, ordering a burger or asking where the bathroom is does not count), especially if you plan to stay there for a couple of months or more.

But many expats and immigrants, particularly from my “brown” part of the world, prefer to muddle through daily life with vernacular scraps, picked up in various situations and locations, and, needless to say, grammatically atrocious. Coupled with histrionic gestures and deliberately choppy English, they manage to make themselves almost perfectly understood, albeit in a primitive, cave-man sort of way. “I-go-mercado, para shopping.” “This-seat-libre, por favor?” “Me gusta this movie. It is muy bien.” “Tiene scissors, chop-chop?”

The real barrier, though, is the cost of learning a language. Well-reputed language schools promise you many grand things – “Speak Spanish like a native in just six weeks! Three months to your dream job as a parasailing instructor in sun-filled Majorca! Looking for love in Spain? Let us teach you the language of loveee!” But they also require you to dig deep into your pockets for the bargain, which most immigrants cannot afford to do.

However, thanks to my avid habit of reading advertisements in the metro (and everywhere else), I came across a language school that was reasonably-priced, and only a five-minute walk from where we lived, near Puerta del Sol. Upon investigation, I discovered that C.E.E. Idiomas was indeed a legitimate language school, complete with an administrative office, three stories of classrooms, and plenty of bright-faced, noisy internationals crowding its narrow staircases – and not, as I had initially suspected, some sinister racket for trapping gullible foreigners on shoestring budgets.

My first day of class I was terribly excited. I’ve always been a bit of a nerd, and loved going to school as a kid. So, I picked out a crisp new Generation kurti, slipped on my favorite orange flats, tossed a purple notebook and Piano pen into my Democracy Now tote bag, and set off bouncing along to class. I wasn’t only going to learn Spanish. Nobody knew it, but I had other intentions. I was friend-hunting.

Unfortunately, my dream of finding a kindred spirit, sitting there waiting for me in the classroom – darkish hair, fairly tall, not unlike myself, whom I would then proceed to hug, and demand, “Where have you been all this time???” – did not quite materialize. None of the students were the right fit. Some were too old (grandmother), some were too young (just out of high school), some had too many responsibilities (committed housewife, mother of two school-goers), and some were just too foreign (Kentucky, USA?). There was only so much we could share or talk about.

But still, peeling off my pajamas and going to class everyday in the fresh morning air, interacting with corporal human beings apart from my husband and the Carrefour lady was admittedly very pleasant. Plus, our Spanish teacher was an absolute riot, and we spent most of the hour laughing, though we didn’t understand half of what she said. I was learning quite a lot, too, very useful and practical things (for example, the important distinction between ojo, eye, and ajo, garlic, which I had confused more than once at the grocery store: “Tiene salsa de ojo?” “Do you have eye sauce?”). And – how can I deny it – I loved being back in ‘school’!

Read Tip #2, Tip #3, Tip #4, Tip #5, and the introductory post of this series!

Thoughts on Leaving Pakistan

Published in the The Friday Times Blog, October 10th 2013

The last time I put thoughts to paper was a year and a half ago, when Z and I moved back to Pakistan from the U.S. It happened very suddenly, under very sad circumstances, and there we were – thrust into a disorienting new life, filling roles we had never anticipated, never wanted, inhabiting, once again, the cloistered, uninspiring world of Lahore’s privileged class.

Much elapsed during the past 18 months in Lahore – much to rejoice and remember. Engagements, bridal showers, weddings. Baby showers, and babies! Farewell parties and welcome-back parties, birthday parties and Pictionary parties.

PTI fever, elections, and Pakistan’s first peaceful political transition. Cliff-diving in Khanpur under a shower of shooting stars, dancing arm-and-arm with Kalash women as spring blossomed in the Hindukush, tracking brown bears and chasing golden marmots in the unearthly plains of Deosai.

I rediscovered my love of history, of abandoned old places that teemed with a thousand stories and ghosts and memories, thanks to a research job at LUMS. I spent many days wandering the cool corridors of Lahore Museum, many hours contemplating the uncanny beauty of the Fasting Siddhartha, whom I had the privilege of photographing up-close. I stood beneath the most prodigious tree in the world in Harappa. I got down on my knees with a shovel and brush during a student archaeological excavation in Taxila, personally recovering the 2, 000-year old terracotta bowl of a Gandhara Buddhist monk.

But, there was also dissatisfaction. Frustration. Restlessness. When we were not travelling, we were in Lahore. And Lahore was, well, warm. Convenient. Static. Living there again was like a replay of our childhood; like watching a favourite old movie on repeat. After a while it got monotonous, somewhat annoying, and a little disappointing.

In Lahore, I could see what the trajectory of my life would be, the next 10 years down. It was all planned out, neatly copied from upper-class society’s handbook, with but minor divergences here and there.

It wasn’t a bad plan. In fact, it was a perfectly good, even cushy plan, one that would have made a lot of people quite happy.

Not me.

There were other things, too, about Lahore, and about Pakistan, things that had bothered me growing up but now seemed magnified to alarming proportions – the incomprehensible extremes of wealth and want, the insurmountable divisiveness of class, and, most worrying of all, the overwhelming self-righteousness and religiosity.

You could not escape it. Everywhere, from TV talk shows to political rallies, drawing rooms to doctors’ clinics, there was a national fixation with religion. Everybody, it seemed, was desperate to convince others – and themselves – of their absolute piety, their A+ scorecard-of-duties-towards-God, their superficial Muslim-ness. Instead of the genuine, unselfconscious goodness that shines through truly spiritual people, in Pakistanis I just saw fear. Religion for them wasn’t about peace, and love, and knowledge. Religion was base. Religion was social security. Religion was a tool of power.

I wanted to say to these superficial Muslims, to all Pakistanis: Just look at the state of our country. Do you really believe that religion has helped us? Has it at any level, be it individual, societal or state, improved the country? Has it alleviated poverty, reduced rape and murder, mitigated corruption?

Have we as a nation achieved anything positive, anything progressive, in the suffocating garb of “religion”?

No. On the contrary, we, as a nation, have become more intolerant, more oppressive, more barbaric, as our outward religious zeal reaches new heights.

And we still do not realize it. The Matric-fail maulvi at the local mosque still preaches that a woman wearing jeans in public is jahannumi, Hell-bound , the TV reporter interviewing an old peasant who has lost his home in a flood wants to know if he kept his Ramzaan fasts, and that educated, apparently “modern” aunty you met at a family dinner launches into a sermon that the reason Pakistan is beset with crises is because we don’t pray enough.

That was the most terrifying thing I found about Lahore, and about Pakistan. It had become a place where no other framework for discussion about the future of the country, about anything at all, was possible. We were mired in religion. We were stuck. We were deeply and hopelessly stuck.

As for the people who thought differently, the elite and “enlightened” class that I belonged to, they responded to the onslaught by retreating further and further into their elite Matrix – a sequestered, protected world where they met up with friends over Mocha Cappuccinos at trendy New York-style cafes, where they shopped for designer Italian handbags in centrally air-conditioned shopping malls, where their children spoke English with American accents and dressed up for Halloween, where alcohol flowed at raucous dance parties behind the gates of a sprawling farmhouse.

It was a parallel universe, where we all lived free, modern lives, like citizens of a free, modern country, utterly disconnected from the “other” Pakistan, the bigger Pakistan, and for all intents and purposes, the “real” Pakistan. Yet perhaps it was our only survival, the only way to keep sane and creative and happy for those of us who chose to live in our native country.

But I could not reconcile myself with it. I found it schizophrenic. Perhaps living abroad had changed me too much. I could not find balance, I could not find peace in Lahore.

So when Z applied to and got selected for a European Union PhD scholarship based in Madrid, Spain, I was thrilled – and a little relieved. Was I looking for an escape? Maybe. Was that the only solution? I don’t know.

When we left Lahore, on that eerie twilight flight in August, our lives packed into just one suitcase and backpack each, it was bittersweet. I was sad to say goodbye to loved ones, to friends and family whom I had spent such wonderful moments with in the past year and a half. I would miss being a part of their lives. And I would miss the incomparable natural beauty of Pakistan – beauty and heritage that is disappearing day by day due to neglect and ignorance.

Yet, I knew that I had to go. I knew that staying in Lahore – “settling for” Lahore – buying joras from Khaadi, attending tea parties, managing servants, the odd freelancing or part-time job at LUMS, was not going to make me happy. And we could not depend on the love of family and friends to sustain us forever. At the end of the day, everybody had their own lives to lead, their own paths to carve, their own hearts to follow.

And that is how we ended up in Madrid.

Sitting here in our apartment, a cozy, parquet-floored 1-bedroom affair, I can hear the babble of excited young voices below the window, a medley of idioms and accents; the clink of glasses and clatter of dishes from neighbouring restaurants; the smoky strumming of a flamenco guitar, the wheezy chorus of an accordion; the cries of Nigerian hawkers and Bengali street-peddlers, and the low hum of the occasional taxi cab, rolling along the cobbled streets of this lively old pedestrian barrio of the Spanish capital.

A new city, new adventures, new memories.