Pakistan

Lingering Fragrance

She needed some green in her apartment.

Before she bought furniture, she was at the flower shop – a subconscious evocation of a fecund childhood, romping in gardens, rolling in lawns, clambering mango trees, picking flowers in the morning for the breakfast table…

“Philodendrons, lilies, ferns, azaleas, bonsai…”

Hmm. She spends long minutes gazing at each plant, fingering the leaves, feeling the texture, inhaling its aroma.

“I’m sorry, I just can’t decide!” she smiles apologetically at the Chinese lady behind the counter. “Everything is lovely, but…” What do I want?

Then, among the flowering pots, in a tangle of pink, yellow, purple, red, blue, she spies a familiar star-shaped white…

She blinks, startled. Is it? It can’t be…bending forward, she buries her face in the modest little shrub bearing the two pale-faced flowers and takes a deep breath…

Suddenly, she’s not in Brooklyn.

She’s in a garden in Lahore on a warm summer’s night. The grass is damp from the afternoon rain. Crickets and other invisible creatures of the dusk trill madly in the bushes, and a velvety breeze rustles in the bougainvillea creepers and Gulmohar above, filling the air with a shower of orange and fuchsia…

It smells sweet, but a subtle kind of sweetness – of budding love, and clasping a dear one’s moist hand, of late-night drives and dewy white bracelets bought from the barefoot little boy on the curbside, of cooing pigeons and clouds of fluttering wings on the rooftop, of twinkling black eyes rimmed with kajal, white blooms wreathed in black hair, and the enveloping scent of flowers in a bride’s bedroom…

“So you want the jasmine, miss?” The Chinese lady grins, her cropped black head nodding vigorously, round black spectacles bouncing on her nose.

Jasmine! Motia…

“Yes, I’ll take the jasmine,” she nods vigorously back.

It sits on a windowsill in her apartment, in a modest little green pot – spreading its delicate, memory-laden perfume over the folds of her new life, a graceful remembrance, a lingering fragrance of the past.

Of New York Spring And Other Things

Published in the Express Tribune Blog, May 24th 2011

Growing up in Lahore, the monsoon was my favourite season – those muggy, motionless afternoons when the air suddenly exploded into a river of orange rumbling down from the sky, leaving jungles in its wake. In the Bay Area, every balmy day of the year was beautiful, except for the miserable characterless spluttering they called “rain”.

In Ithaca, my favorite season was Autumn – a firedance in the sky, bold and blazing, curling flames at your feet – and in New York, it has to be spring, the teenage of nature, blooming poetry from every stem, every lilting branch, a breathtaking ballet of pink and white to melt the numbest of hearts.

On such a blossomy New York morning last week, my colleague Ryan and I were at Ground Zero, jostling through hundreds of New Yorkers and out-of-towners to catch a glimspe of President Obama as he arrived to lay a wreath at the September 11th Memorial Site, giving symbolic “closure” to the victims and families of the 9/11 attacks following Osama bin Laden’s death.

We didn’t see him, not even a fluttering hand through a darkened car window. But Obama became irrelevant once we actually started talking to people and recording their reactions to the news.

Reactions were predictable: One African-American woman beamed with pride that Obama had been in office “to do this urgent and important duty”. A man who had lost four friends in 9/11 said he felt a sense of “relief” and “joy” beyond words; a young Latino-American who had recently joined the New York National Guard said that Osama’s death was a source of “unity” for the people of New York, that it showed “how Americans come, in all shapes and forms, whatever nationality you are, whatever colour you, you come as one.”

But what was unpredictable was these people’s, these ordinary, middle-class, tax-paying people’s calm acceptance of the fact that yes, this “war” was “not going to end with the death of one person”, and, more disturbingly, that it needed to go on, that it should go on. In the words of one 67-year old ex-Marine, “We have to be there in all of these countries to assist…so we can crush these people when they come in to try and hurt us. It’s not over.”

While Ryan asked the questions and I filmed behind the camera, I thought about the questions I would have liked to asked these people: “But do you know the real victims of your country’s fallacious war? Do you know who actually pays the price? What do you have to say to the families of the tens of thousands of innocent men, women and children killed in Afghanistan, in Iraq, in Pakistan because of this war? Were their lives less valuable than the 3,000 Americans who died here 10 years ago? Do you not see that what you’re calling ‘patriotism’ and ‘duty’ is decimating entire societies, entire nations as we speak?”

I said nothing of the sort. I was a journalist, and Pakistani on top of that, and the last thing I wanted to in that sort of crowd was get into an argument.

Turns out, somebody else was there to do it for me – a lanky, bespectacled and very articulate white dude by the name of Sander Hicks, founder of the “Truth Party”, a grassroots political group that believes in exposing, among other things, that 9/11 was a hoax. Wearing a black T-shirt with the words “9/11 Is A F****** Lie!” emblazoned on the front, Hicks shouted maniacally but fearlessly to the crowd, “Why am I here? Am I here to celebrate and validate a murder? Without a trial, without due process? Or am I here to think about what is really happening in our country? Do we justify war and torture based on 10 years of lies? I say no! And I don’t care if there’s a million people here saying I’m an a**hole, just for standing up for peace and truth!”

I’m still surprised that he got away with saying that, and a lot more, without even a scratch, though there were several jingos in the crowd who would’ve liked nothing better than give the provocative Hicks a square punch in the jaw. But shouting back “A** hole!” is about as far as they let their anger go.

Then, in the middle of the fray, a red-faced, white-mustachioed little man broke in. Wearing a black leather jacket covered in Vietnam insignia, he cried in a thick Texan drawl: “You know what I would’ve done if I were President when 9/11 happened? I would’ve nuked the entire Middle East, starting with Mecca!”

So far that day, I had been watching and listening to everybody almost in the third person, a perfectly neutral body. But at those words, I felt my heart plummet like it would at a vertical drop on a Seven Flags rollercoaster, and a row of goosebumps shot up my spine as if I were suddenly caught in an Arctic gale wearing a T-shirt. I looked up from the camera. My eyes stung; I thought I was going to cry.

It was pure reflex. Something essential and sacrosanct, seeded deep in my soul, had been momentarily convulsed, and at that moment I could’ve clawed out the old geezer’s eyes.

There was a collective gasp from the crowd, and people were quick to admonish, “No, no, that’s crazy!”, “Not all Muslims are bad!”. Clearly, the guy was a loony, and it would’ve been stupid to take anything he said seriously. But his words stayed with me long after his black leather jacket disappeared into New York’s hubbub of loonies, and I thought, “So this is how it feels – to be on the ‘other side’ of extremism?”

We’ve had plenty loonies from our part of the world dispense similar tirades about the West, about the U.S., Europe or Israel – and God knows I’m not a fan of those parts of the world or their foreign policies. But to an ordinary citizen, who has as little control over what their government does as we do over ours, how would it feel, to be so sweepingly abused, to hear people talk about obliterating our very existence, burning flags and defacing temples as if it would have no consequences, as if it would offend or incite nobody; even for someone like me, deeply suspect of nationalism and all other -isms in general, I admit that it would hurt – that it does hurt.

It’s complicated. It’s complicated when imperialism is involved, when capitalism and neo-colonialism is involved, when there is a legitimate anger and resentment and struggle for justice, like in Palestine, or Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. It’s difficult to talk without the invective, without the bitterness, when you have been truly wronged; but all I can say is, let’s let humanity win.

That’s all we have, to keep us alive and save us from total catastrophe. At the end of the day, it’s the ordinary citizen’s sympathies and consicence that we can appeal to, we can touch; it’s their ordinary humanity that we can depend on, not any politician’s or government’s. Let’s not sacrifice that, no matter which ‘side’ we come from.

Not Being

If home is where the heart is, my heart is forever moving, a gypsy

If a piece of cloth and a stadium slogan is the basis of nationalism, I have no nation

If piety is measured in prayers, in a ledger in a language I don’t understand, I am a heathen

If speech is an adequate expression of sentiment, I have no words

If living by somebody else’s rules is sociability, I am a misanthrope

If white is black and black is white, then I don’t exist.

Is there a Pakistan to go back to?

Published in The Express Tribune Blog, January 20th, 2011

Last week, my husband and I finally booked our return tickets to Pakistan. It was a proud moment, a happy moment, not only because we had been saving to buy them for months, but because we had not been home in nearly two years.

Two years! It seemed like a lifetime. We had missed much: babies, engagements, weddings, new additions to the family and the passing of old, new restaurants and cafés, new TV channels, even the opening of Lahore’s first Go-Karting park. I could hardly contain my excitement.

Yet, my excitement was tainted by a very strange and disquieting thought – was there even a Pakistan to go back to?

My family and friends would be there, yes, and the house I grew up in, and my high school, and the neighborhood park, and the grocery store where my mother did the monthly shopping, and our favorite ice cream spot…

But what of the country? And I’m not talking about the poverty, and corruption, and crippling natural disasters – I’m talking about a place more sinister, much more frightening…

A place where two teenage boys can be beaten to death by a mob for a crime they didn’t commit, with passersby recording videos of the horrific scene on their cell phones…

A place where a woman can be sentenced to hang for something as equivocal as “blasphemy”…

A place where a governor can be assassinated because he defended the victim of an unjust law, and his killer hailed as a “hero” by religious extremists and educated lawyers alike…

This is not the Pakistan I know. This is not the Pakistan I grew up loving. This bigoted, bloodthirsty country is just as alien to me as it is to you.

The Pakistan I know was warm, bustling and infectious, like a big hug, a loud laugh – like chutney, bright and pungent, or sweet and tangy, like Anwar Ratol mangoes. It was generous. It was kind. It was the sort of place where a stranger would offer you his bed and himself sleep on the floor if you were a guest at his house; a place where every man, woman or child was assured a spot to rest and a plate of food at the local Sufi shrine. A place where leftovers were never tossed in the garbage, always given away, where tea flowed liked water and where a poor man could be a shoe-shiner one day, a balloon-seller the second, and a windshield-wiper the third, but there was always some work to do, some spontaneous job to be had, and so, he got by.

My Pakistan was a variegated puzzle – it was a middle-aged shopkeeper in shalwar kameez riding to work on his bicycle, a 10-year old boy selling roses at the curbside, a high-heeled woman with a transparent pink dupatta over her head tip-tapping to college, with a lanky, slick-haired, lovelorn teenager trailing behind her.

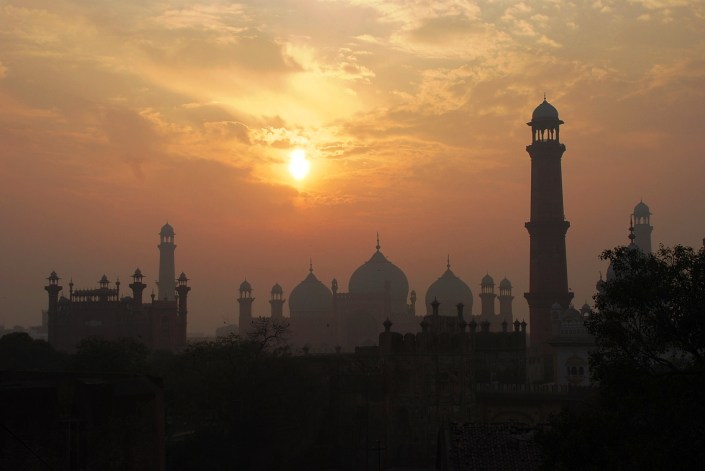

A Michael Jackson-lookalike doing pelvic thrusts at the traffic signals for five rupees, a drag queen chasing a group of truant schoolboys in khaki pants and white button-down shirts. Dimpled women with bangled arms and bulging handbags haggling with cloth vendors, jean-clad girls smoking sheesha at a sidewalk café, and serene old men in white prayer caps emerging from the neighborhood mosque, falling in step with the endless crowd as the minarets gleamed above with the last rays of the sun in the dusty orange Lahore sky.

My parents were practicing Muslims, and religion was always an important part of my life. Like most Pakistani children, my sister and I learnt our obligatory Arabic prayers at the age of 7; I kept my first Ramadan fast when I was 10, bolting out of bed before dawn for a sublime sehri of parathas, spicy omelettes, and jalebi soaked in milk. By the time I was 13, I had read the Holy Qur’an twice over in Arabic, with Marmduke Pickthall’s beautifully gilded English translation.

But beyond that – beyond and before the ritual, or maddhab, as they say in Sufism, came the deen, the heart, the spirit of religion, which my parents instilled in us almost vehemently, and which to me was the true message of Islam – compassion, honesty, dignity and respect for our fellow human beings, and for every living creature on the planet.

So, while we as Pakistanis had our differences, and practiced our faith with varying tenor – some were more “conservative” than others, some more “liberal”, some women did hijab while others didn’t, some never touched alcohol while others were “social drinkers” – we were all Muslim, and nobody had the right or authority to judge the other, no red-bearded cleric or ranting mullah. There were no Taliban or mullahs back then; if they existed, we never saw them. Not on TV, not in the newspapers, not on the streets, in posters or banners or fearsome processions.

It wasn’t a perfect society – far from it. Inequality and abuses were rampant, and daily life for a poor person could be unbearable. But they were the kind of problems that every young, developing, post-colonial nation faced, and the worst thing that could happen to you when you stepped out of the house was a petty mugging or a road accident, not a suicide blast. It was chaotic, but it was sane.

Then 9/11 happened, and society as my generation knew it began to unravel.

It started as a reaction to the U.S.-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and the “clandestine” war in Pakistan – a reaction shared by Pakistanis across the social spectrum. But somewhere along the way, the anger and grief mutated into a suicidal monster of hatred, robed in religion and rooted in General Zia’s pseudo-Islamic dictatorship of the 1980’s and the U.S.-funded Afghan jihad. Pakistan was engulfed by a frenzy, an unspeakable frustration, not only at the neighboring war that had expanded into its heartland, but at everything that was wrong with the country itself. And, like the hysteria that fueled the Crusades or the 17th-cenutry Salem witch-hunt, religion was the most convenient metaphor.

I don’t claim to understand it all, or be able to explain it. But what I do know is that, alongside the two purported targets of the “War on Terror”, there is no greater victim of 9/11 than America’s indispensable, ever-“loyal” ally and doormat, Pakistan itself.

Maybe I’m romanticizing a little. Maybe I’m being over-nostalgic about the past, and the Pakistan of my childhood. But that’s the only way I can retain some affection for my country, the only way I can sustain the desire to go back and live there – if I know and remember in my heart, that it has been better. That it was not always like this. That it was once rich, multifaceted, beautiful, tolerant, sane – and can be again.

Warmly Winter

Published in Pakistan’s “Women’s Own” Magazine, December 2010

It’s finally happened.

The knock on the door, and an outstretched palm containing a steaming plate of food.

Chicken-and-veggie rice casserole or Palestinian maqluba, to be specific, on a plastic white flower patterned plate.

Yes, Mama Jama the landlady brought us dinner!

And it couldn’t have been at a more opportune time. In my missionary zeal for bhoono-fying, I had just burnt the aloo gosht. Mama Jama probably smelt the aroma of charred onions drifting down the staircase and took pity on us.

Of course, it’s not that I was expecting her to. It’s not the reason I’d show up at her doorstep every other week with a lovingly-prepared bowl of kheer, zarda or melt-in-your-mouth gulaab jaaman.

I was just being neighbourly.

And testing out my (extremely novice) Pakistani dessert skills.

And skirting the guilt of single-handedly consuming 2 pounds of sugar in one afternoon – an inevitability if said bowl of kheer or gulaab jaman remained in my apartment, thanks to the relentless sweet tooth inherited from my dad.

Yes, I am an epicure (fancy word for greedy). If it were up to me, I’d either be at home baking apple pies and chewy chocolate brownies before proceeding to do justice to their goodness, or I’d be outside in a café or bakery sinking my teeth into the congenial warmth of freshly-baked cinnamon roll, red velvet cupcake, almond croissant, pumpkin pie, strawberry cheesecake, piping hot apple pie or chewy chocolate brownie, with my nose between an equally delicious New York Public Library book.

Luckily, I have a very active and health-conscious husband, who, a) makes sure that I never find more than 50 cents in my wallet at whatever random moment the sweet tooth calls, rendering me helpless in the face of heavenly-smelling street stalls and petite cafés with bothersome minimum-cash policy; and, b), manages to drag me out somewhat regularly for a bit of exercise.

Our current physical activity is rock climbing – on the boulders of Central Park. So, if you ever happen to be strolling near Columbus Circle on a Saturday morning and see two figures attached to a rock – one, strong, athletic, moving swiftly across the rock face like a demo picture from “The Self-Coached Climber”, and the other a ball of play-dough smushed against the wall – you’ll know it’s us.

I have to say though, as much as I was dreading another East Coast winter, there is a charm about it, a crisp-coloured storybook charm.

I don’t know if it’s in my brown BearPaw boots, or the toasty knit cap and woollen mitts that I gleefully don every morning; the feel of a hot Starbucks hazelnut latté between my fingers or the beautiful bareness of Central Park, the crunch of leaves beneath my feet, and the blossoming of Christmas lights on 5th Avenue. Ice skating at Bryant Park, followed by a cup of steaming apple cider and a stroll through the dazzling holiday market, a veritable Santa’s workshop; the pleasant conviviality of huddling with strangers in the 8×8 floor space of Kathi Rolls or Mamoun’s Falafel in the Village, exchanging smiles over a shami kabab roll and shared hearth; or, maybe it’s just the indescribable comfort of home, where you return from the cold with relief and bliss in your heart – given that the heat is working, which you can trust it to be if you’re on food-exchange terms with the landlady.

Of course, slopping through puddles to do your laundry or buy a carton of milk is another matter, as are the thundering hailstorms that sound as if they’ll break straight through your skylight and flood the apartment, the sodden subways and the razor-sharp winds whipping through the labyrinth of high-rises ready to slice off your nose, or having to wear the same inflated down jacket for five months until you are resigned to looking like the Michelin Tyre Man in every photograph.

But no matter how much I complain about it now, winter was always my favourite season in Lahore. I would dream about it the whole year – dream of the day, sometime in November, when the gas heaters were unearthed from the store room and dusted out, when bright chunky sweaters and printed Aurega shawls were unpacked and sunned to get rid of the minty smell of mothballs.

The marvelous halvas my mother would begin to ghot-ofy in the kitchen, gajar, anda, sooji, and my personal weakness, chana daal, the rich smell of ghee and shakkar permeating the entire house in its intoxication; the blood-red pomegranates and succulent oranges we’d eat sitting out on the dewy lawn, the dogs snoozing under the chairs, wrapped up in a brown khaddar shawl that smelt of faded Chanel No. 5.

Even going to LUMS in the morning was fun, dressed in a gigantic sweatshirt and sitting on the sidewalk across the cafeteria after class, watching the steam from the PDC teacup mingle with our cloudy breaths, as the fabled Defence fogs circled in around us from the empty stretches of Phase 5, and we pretended we were in a Sci-Fi movie…

Winter was synonymous with Ramzaan and Eid, with grand tented shaadis, Capri nashtas and apple sheesha at MiniGolf, starry walks, sunny picnics, bonfire dances; lying curled up on a floor cushion in front of the heater in your living room, looking out at the lights of the 600-year old Lahore Fort from the rooftop of Cuckoo’s on your cousin’s December birthday, or blushingly saying “Hello” to your soul mate in the back rows of a Gymkhana concert…life didn’t get any better than a winter in Lahore.

And though I am here now, and New York City beckons with its lights, treats and newfound friends, and I am happy with my new life, I still dream of those magical Lahore winters, old friends, old shawls, ancient forts, and the fresh, pink-cheeked days that hold some of my most precious memories …

And that’s alright. Because time doesn’t flow if you don’t dream.

The Third World Burden

Published in The Express Tribune Blog, November 9th 2010

At the documentary production company where I worked over the summer, one of our ongoing projects was a film about four Senegalese teenagers chosen to come to the U.S. on basketball scholarships. At the end of the film, the boys return to Senegal, and one of them says, “We were the lucky ones. Now it’s our turn to give back”.

“Ah, that noble, philanthropic spirit!” my boss once remarked with an ironic laugh, as we had just finished watching a fresh cut of the film. “Isn’t that just so African?”

“No,” I thought to myself, slightly annoyed at her levity. “There’s nothing African about it. That’s what anyone would say…” And as these thoughts went through my mind I suddenly realized that this attitude, this sentiment that the young Senegalese boy had expressed and which to both of us was so completely natural and unquestionable – this attitude was not universal.

It was a Third World phenomenon – a Third World burden.

We’ve all felt it, growing up in Pakistan – an intense altruism combined with intense guilt. We know that we haven’t done a thing to deserve the blessings we were born with, the schools, books, servants, cars and computers that we took as a matter of course; and that knowledge makes us extremely uncomfortable, especially when we go out and see the reality on the streets.

So, we feel this compulsion, this need to absolve ourselves by “giving back”, by doing charitable works, by devoting some part of our lives to this country that gave us so much simply by a stroke of chance.

This sentiment formed a large part of my motivation for applying to Journalism School. Journalism, for me, was a way to “give voice to the voiceless”. It was my way to “make a difference”, to “bring about a change” in my country, and other such lofty objectives, which I liberally elucidated in my personal statements.

I was being serious, too. Ever since I can remember, I’d had this sense of responsibility to “represent” Pakistan, to tell the world “the truth” about my misunderstood and maligned country. How and why I wanted to do this was irrelevant – I just knew that I ought to, that it was my duty. And so, I would dutifully watch the 9pm PTV Khabarnama with my dad every night, scan the front pages of The News or Dawn every morning before going to school, glue myself to CNN and BBC as soon as I returned home in the afternoon – feeling very good about myself, very clever and “aware”, because, after all, this was going to be my cause, this was my calling.

Then I came to the U.S., and found a precise pigeonhole sitting in wait for me – the young, educated, uber-ambitious, hyper-intellectual Pakistani-Muslim woman, an increasingly-coveted creature in the West. Falling into this pigeonhole, I was expected to be an authority on “all” things Pakistan – at least the Western conception of it – from the “War on Terror” to the safety of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons, relations with China and India to the sociology of the Taliban, violence against women, the rights of minorities, jihad in Islam, arranged marriages, the latest connivances of the President/Prime Minister/Military Dictator, whichever incompetent and corrupt nutcase happened to be in power, the number of casualties in the latest suicide attack…

I couldn’t have any other interests, and people didn’t expect me to converse about anything else. Anything but the destruction, misery, and despicable politics of my country.

And, to a degree, I lived up to the stereotype.

When Musharraf declared emergency in November 2007, when Benazir was assassinated in December 2008, when suicide bombs and drone attacks were reported in the New York Times, the people I passed by in the corridors on my way to class would look at me with an intense pity, even a kind of awe, as if I were the most unfortunate person that they knew. As if, every time a missile struck or a bomb exploded anywhere in the country, whether in Islamabad or the remotest part of the tribal belt, I was somehow directly affected, I somehow had an obligation to grieve. And I would return their gazes with a wan smile, a nod of the head, acknowledging their sympathy and concern with the air of a martyr.

But you know what? Sometimes I faked it.

Deep down inside, I knew this person wasn’t me. This person, posing to be the face of the Pakistani nation, a walking repository of information and statistics, the sharp-witted political analyst or TV talkshow host of tomorrow – it wasn’t me. I wasn’t an authority on anything except my own experience, and my own experience was as far removed from the poverty, violence and corruption that comprised of the news headlines as could possibly be.

And what if – what if I didn’t even want to be that person?

What if all I wanted to do in life was travel the world and take beautiful pictures? Did that make me a “bad” journalist, a “bad” Pakistani?

Once, one of my father’s friends – an “uncle” – asked me what kind of “issues” I was interested in covering as a journalist. “Politics, economics, business?” were the options he gave me.

I decided to be bold this time. “Actually, I’m more interested in culture and travel,” I said, stealing a glance at the yellow National Geographics that lined the bookshelf. “I want to be a travel writer.”

The uncle’s face fell to a grimace, as if I’d said I wanted to be a tight-rope dancer at Laki Rani Circus. “Well, there’s a lot of use in that,” he muttered.

So we come back to the Third World burden, where every son or daughter of the land who is able to “escape” abroad for a better education or a better life is unspokenly expected – no, duty-bound – to “give back”, to “represent”. Indeed, to have other aspirations or interests would be considered strange, unworthy, or irresponsible, a “waste”.

Don’t take me wrong. I love my country, and I do want to give back. But I don’t want it to be out of “duty”, or worse, guilt. Most of all, I dislike the stereotype, the stereotype that hounds countless other Pakistanis, especially journalists like myself, that prompts the same automated response from all media outlets in New York City: “We don’t have any use for you here. However, if you were in Pakistan…”

Yes, I know. I need to be in Pakistan, I need to talk only about Pakistan, if I want to be a journalist, if I want to further my career, if I want to make a name for myself. I need to write an exposé on madrasahs or profile Faisal Shehzad, interview a militant, acid burn victim, or a young girl orphaned by the floods – I need pictures of devastation, tales of suffering, tinged with the spectre of extremism, I need to exploit my country’s wretchedness on HD-cam for the world to see, and then tell myself I’ve done a good deed, that I’ve done “my bit” to give back.

No, thank you. Give me a ticket to teach English in China, a spot on a Mount Kilimanjaro expedition or a photographic tour of the Silk Route any day. I’ll give back when I want to, the way I want to.

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Next →